Arles and the Reattu Museum

The exhibition gradually took shape. The renovated museum and the cultural impact of the town of Arles–largely due to the photography festival that developed from the initial Rencontre d'Arles–spurred Jean-Maurice Rouquette and Lucien Clergue to turn the occasion into an exceptional event. They ardently hoped that Picasso would join the project, embrace it, and appropriate it. The photographer who had his trust and the curator who admired him so were both eager to pay homage to the master in the museum.

Two months later, on May 24, Picasso called Rouquette again and said: "Come on over, I have a surprise for you." The meeting was set for the following day; this time, Rouquette went alone. "I prepared a few things and threw around a couple of ideas. Let me know whether any of it would be of use for your exhibition." The studio was filled to the brim with cutout papers, sorted and unsorted, kept "because I may be able to use them for my work." They were scattered all over the place. As Jean-Maurice Rouquette recalls, "the house was strewn with parcels. Picasso received sacksful every morning." His infatuation with paper, with printer matter, was a constant throughout the artist's life, and he continued to sort out the huge piles of mail that he received every day.

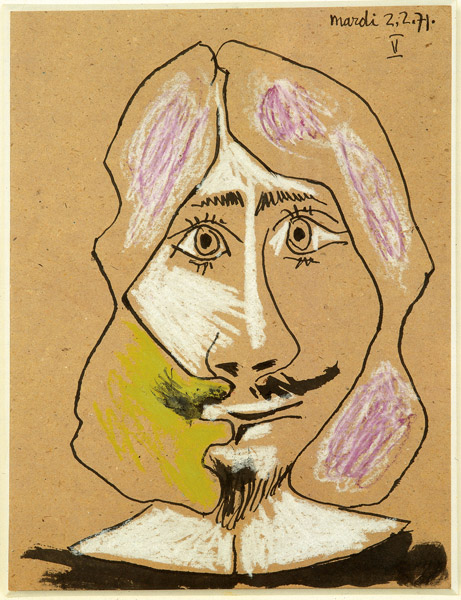

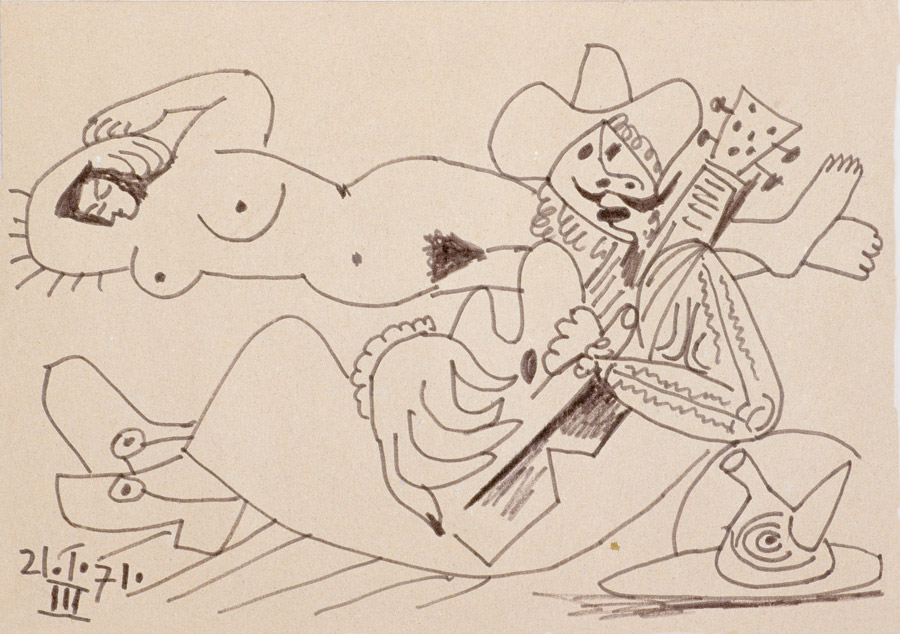

Picasso disappeared for a moment and came back carrying a pile of drawings. Rouquette is still moved when he describes his recollection: "An unimaginable series of veritable masterpieces that he had just produced paraded before my dazzled eyes. They were extraordinary in their number and in the beauty of their line." Picasso subtly introduced the art of imbalance into each composition, creating a dialogue between black and white, between fullness and void, line and color. It was a continuation of the collection of one hundred and ninety-four drawings the artist had shown in the Leiris gallery in Paris. Overcoming his initial speechlessness, Rouquette had to focus on making a selection, which was obviously no easy task. Looking over the pieces together, they chose fifty-seven, spanning from December 31, 1970 to February 4, 1971, Jacqueline urged the painter to donate the selection to the museum. Picasso, although very generous, was reluctant to part with the pieces. The explanation offered by his renowned dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler was that for Picasso, painting was like a personal journal, an autobiography of sorts that one is resistant to disclose, something one keeps to oneself. It was a long wait for Rouquette; the artist hesitated. Finally, by the end of the evening, Picasso said, "If you like them, go ahead and take them. But first you must look over them again and tell me whether you really do like them." Rouquette examined each drawing carefully and then thanked the artist profusely for such an exceptional and unexpected gift to the museum. The artist perceived the intensity of the curator's emotion and decided to tease him. In a mischievous tone, he added: "He can take them, but first he must sign a receipt." The artist handed him a thin sheet of paper and said, "A receipt, but on the condition that it fill up the entire surface of this paper."

Rouquette diligently did as he was told and then handed the sheet back to the artist, who laughed, folded it in four, and dropped it into the aquarium.

At midnight, Rouquette said goodbye to Picasso "with an avid, penetrating gaze, preparing, as usual, to work through the night." Rouquette got into his car, suddenly gaining full awareness of the value of his load. Picasso waved at him cheerfully and said, "Well, there you have it. That was a good day, wasn't it?" They were never to meet again.

Summary

Summary