Keeping art alive

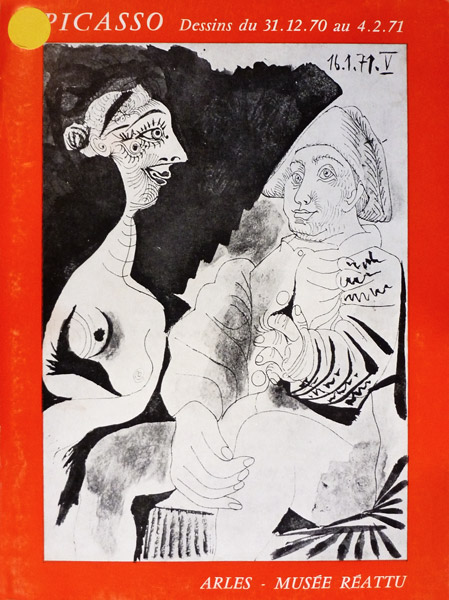

This body of drawings belongs to what art historians have referred to as the "final period," whose beginning is set at different times depending on the criteria of one scholar or another. There was nothing "final" about this period for Picasso, much though his production was interrupted for several months in 1965. The artist knows, feels, suspects that his work will come to a halt, but he takes no heed. He draws, paints, etches, and produces as much as he can, even though he has stopped sculpting, driven by the urgency to tap into the essence of his creations and discover other forms of expression. Showing his virtuosity, he multiplies his experiences, pushing them to the limit, much though critics and art historians have long turned their noses up at a period in Picasso's production that is not easily understood. He wanted to confirm that age and illness had not stripped him of his perfect mastery of materials. The success of his highly detailed print work convinced him that it was by no means so. Picasso worked with the awareness of all he had yet to explore, to leave to younger generations, as if he feared to see art die along with him. Hélène Parmelin, one of the few people with whom Picasso spoke freely about his doubts, describes the artist's last reflections in her book Voyage en Picasso: "I have the feeling that I'm approaching something [...] I am managing to say things... I have only just begun... What I have to do is find what is natural, the way of making things natural, so that painting can be intelligent enough to become the same as life itself […]."

In May 1970, a major Picasso exhibition opened at the Palais des Papes in Avignon. Most of the one hundred and sixty-five works, produced between 1969 and early 1970, had never been shown. Yvonne Zervos had been in charge of curating the show, but died shortly before the opening. Once again, Picasso held nothing back, granting himself absolute freedom; the show was literally torn apart by the critics, as would be the 1973 exhibit as well. Reviewers were scandalized by its being hung in the Grande Chapelle, particularly given all the liberties Picasso took, with many of his canvases full of erotic imagery "counter to public morals and good taste." His work was unfairly interpreted given the age of the artist, whom an uncharitable Douglas Cooper qualified in 1973 in Connaissance des arts magazine as "a frenetic dotard in the anteroom of death."

Summary

Summary