The Making of the Gaze

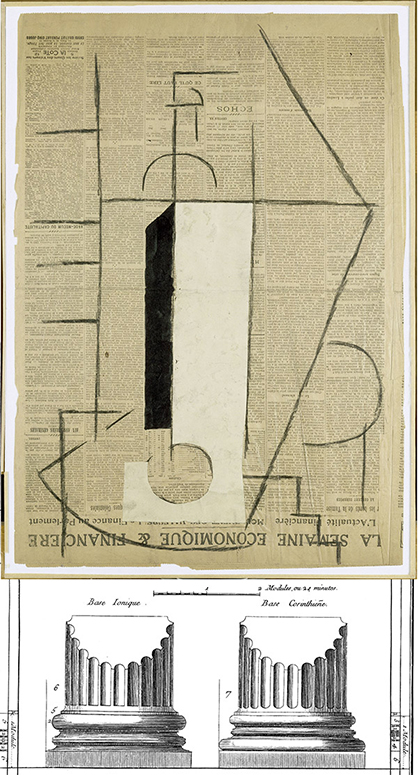

The bottle that has been identified appears in a traditional layout:

- The bulging part of the bottle is located in the large lower square of the newspaper page, in a central position.

- The width of the bottle corresponds to that of one page module.

- The bottle is built upon the field lines of the page, as in a mirror image of the page.

- A three-dimensional space is established, in a stylized manner, by the sketchy representation of a geometric perspective: a horizontal line toward which two diagonals converge.

Next, a second remark: the bottle is not defined by its use, but rather by its formal features:

- It is a surface,

- developing in a three-dimensional space...

- … in which it shares the interior and the exterior.

- The bottle is made up of different parts,

- that are in proportion to each other, in harmonious relationships,

- based on an interplay of simple forms.

This presentation, which is both traditional in terms of the page layout and fragmented in terms of the bottle, pertains to a codified genre: the visual dictionary. In this sense, this "bottle" could be compared to other images with a didactic purpose. For example, let us have a look in Diderot and d'Alembert's Encyclopedia, at a plate titled "base des cinq ordres avec celle nommée Attique” (base of the five orders, with one known as Attic). In the second row, on the left, Diderot shows a base with a standard measure next to it and a ruler above, seen simultaneously from the front and from above. Therefore, the two perspectives are, in principle, comparable. However, the difference between Diderot and Picasso is evident: Diderot shows the figure at a glance; it is recognizable right away. Picasso, on the other hand, allows his figure to appear gradually, introducing the notion of time into the construction of the figure.

A fourth narrative discourse is hence established: that of perceptive capture–saisie–in and of itself, since the object does not appear right away and its constitution develops along with the constitution of the viewer's perception.

The practice of deferring perception (what in phenomenology is referred to as epoché), which allows the figure to unfold slowly, remotivates the figure of the bottle. The viewer does not, strictly speaking, re-cognize what he or she already knows. He or she discovers what remained to be known: the combination of geometric relationships at work within a bottle. The bottle is hence stripped of its use value and rendered available for a true perceptive capture, focused on its appropriation.

Summary

Summary