The Making of a Bottle

Let us set aside the first approach to this collage in which apparent a-signification provokes the viewer. Gaining access to knowledge by taking on the challenge of this provocation implies assuming the existence of a meaning. Let us then examine the piece in further detail.

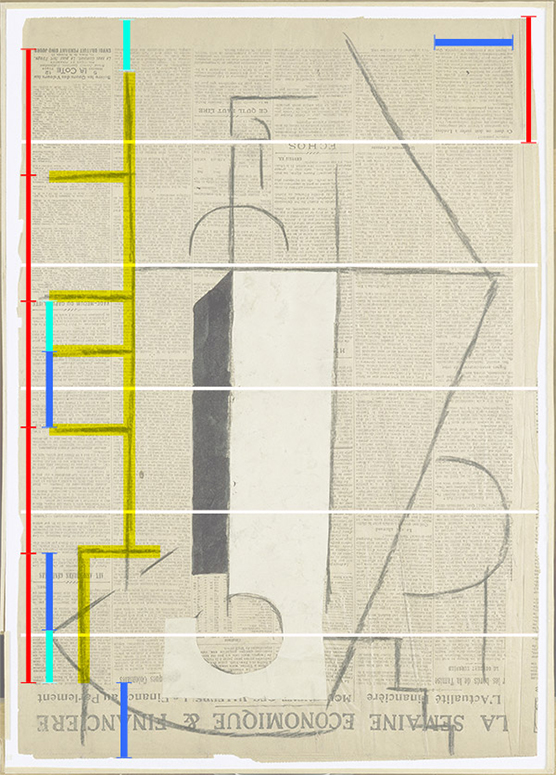

Faced with a juxtaposition of disparate elements–a newspaper page, cut and pasted vellum paper, charcoal lines, a surface treated with India ink–the first account, clearly very general, could be one that connects the elements spatially.

Picasso explores the properties of a 62.5 x 44-cm page of newspaper. The width of the page can be divided into five equal parts whose three first lines of separation are drawn with charcoal. The height of the sheet, in turn, can be divided into six equal parts. The first two lines are drawn with charcoal; the third correspond to the geometric midpoint of the page, and the last is again drawn with charcoal. The resulting grid creates a module.

The height of this module is carried over several times to a segmented vertical line on the left of the composition. This segmented line also indicates a second measure: the width of a column of newsprint. The segmented line thus appears as a scale indicating the width of a newspaper column, the height of a page module, and the distance between the two; in other words, three measures. These three measures are what make it possible to construct the ensemble of elements in the visual center of the composition: the height and width of the geometric figures, the arc of the ellipses.

The ensemble of these references reveals the autonomous visual areas each of which constitute a unit. The shape of each one, their copresence, and their assemblage govern their semantism. From top to bottom, we see a lip, a neck (together forming a bottleneck), a shoulder, and a bottom (heel) of a bottle. The area of the body, although it can be placed between the shoulder and the heel, is more problematical.

Let us start out by examining the white pasted paper. At the bottom, it defines a cutout heel. It outlines the heel of the bottle, and it is in this sense that it is legible in its entirety, since there is no indication of the contrary. Therefore, the white vellum represents the outside of the bottle at the level of the body.

If we mentally trace the outline of the bottle between the shoulders and the heel, we get a body formed by the black parallelepiped and the white external figure. The viewer has to resort to an optical effect by moving from right to left of the piece in order to see the black parallelepiped plane disengage from the white surface and "turn" on an axis, thus forming the inside of the bottle. What occurs is that, as the viewer moves, this two-dimensional area in the piece acquires the volume of the bottle's interior.

Let us review the sequence of actions: we created a scale with three measures. Based on these measures, we drew lines and ellipses in proportion to each other, following a vertical distribution; we folded back the planes of the lip and the heel, and pivoted the black plane. The bottle is the result of this sequence of actions. The "author" Subject gives a series of instructions to the "viewer" Subject, just as in a cook's recipe! This set of instructions can be analyzed in a discourse that is built on a pragmatic dimension (the dimension of action): a guide for assembling a bottle.

Now that we have identified a bottle, the following question is fairly simple: what is the point of representing this entirely trivial bottle in such an obscure way?

Summary

Summary