Picasso at the Heart of Arab Manifestos : building Another Modern Art

As early as 1938 in Egypt and 1951 in Iraq, two pivotal manifestos of Arab modernity placed Picasso at the core of their movements. Although Picasso, the inventor of Cubism—the most important formal revolution of the twentieth century—did not sign any manifestos in Italy, Russia, England, or the Arab world, the writers of avant-garde manifestos were often inspired by the painter.

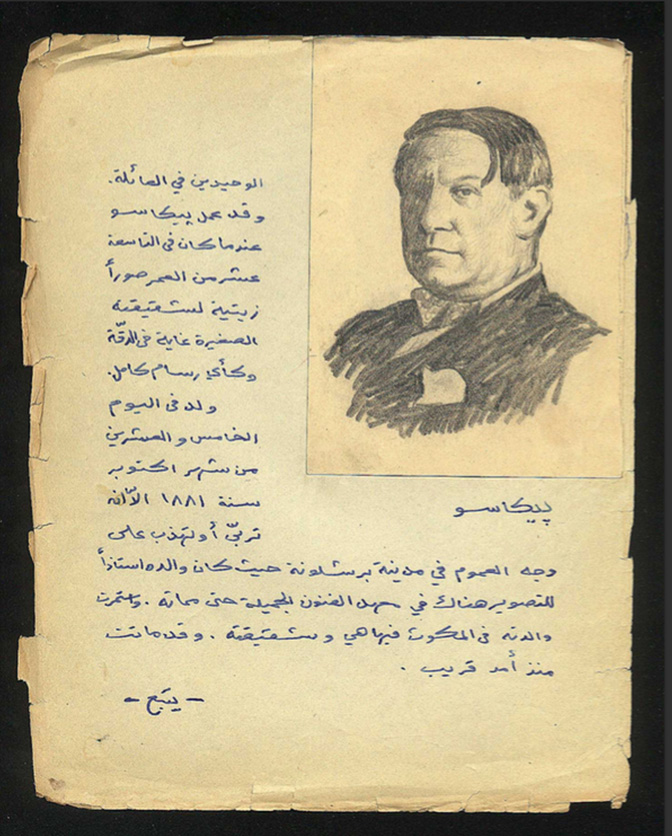

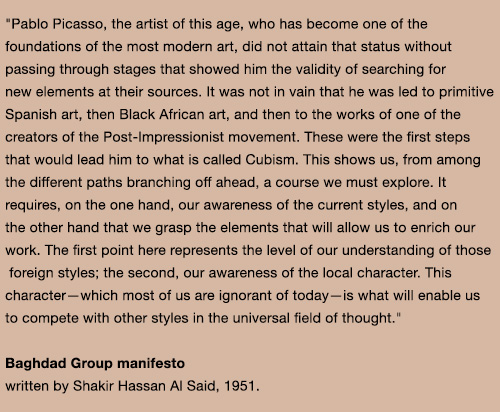

The Art et Liberté group—led by the writer Georges Henein and including the painter and critic Kamel el-Telmissany, the writer Anouar Kamel, his brother the painter Fouad Kamel, and the painter and theorist Ramses Younan, who introduced Surrealism to Egypt and had ties to André Breton—followed along the lines of international Surrealism. In their 1938 manifesto, a four-page pamphlet titled Vive l'art dégénéré [Long live degenerate art] and headed by a reproduction of Guernica, they stated: "From Cézanne to Picasso [...] all the best that contemporary artistic genius has produced, all that modern artists have created that is most free and valuable in human terms is insulted, trampled upon, forbidden." This stance emerged after the Nazi regime organized an exhibition in 1937 vilifying "degenerate art." In 1944, in Iraq, Nazar Saleem, brother of the painter Jawad Saleem, translated several excerpts from the biography of Picasso published by Gertrude Stein in a handwritten magazine. Also in Iraq, the manifesto of the Baghdad Group for Modern Art, written by the young Shakir Hassan Al Said in 1951, proclaimed the birth of a new school of art in the name of both Iraqi and universal civilization. The manifesto, gathering the younger generation of modern art in Iraq, was published in Beirut in the magazine Al-Adab. The only two artists mentioned in this foundational statement were the thirteenth-century miniaturist Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti, the leader of the school that was presented as the bastion of Iraqi pictorial art, and Pablo Picasso, whose output was described as "one of the cornerstones of the most modern art."

First in 1982 and again in 1985, the Iraqi artist Jamil Hamoudi (1924-2003) wrote an account of two previous encounters with Picasso. The first, at the Musée de l'Homme, during which they discussed the arts of Mesopotamia, was the most decisive, spurring him to explore the creative potential buried in his own cultural heritage. When Hamoudi told Picasso how much he and Jawad Saleem admired him, Picasso was surprised by the fact that Iraqi artists were turning to the West for inspiration, and urged them to look to their own country instead. Picasso's interest in non-Western primitive art was a constant source of inspiration for modernists in Iraq and in Egypt, both countries endowed with extraordinary remains of ancient civilizations whose figurative traditions these artists would later draw upon.

Jawad Saleem and later Dia Al-Azzawi, who began by studying archaeology, worked at the Iraqi Art Museum, founded in 1922 by Gertrude Bell, where they were in direct contact with Sumerian and Babylonian artifacts. This contributed to Selim's development of a vocabulary of symbols (horse, bull, crescent moon) and techniques (bas-relief, the use of ochre and orange) which at times overlapped with that of Islam and led Al Azzawi to shape his characters' masks with hollow eyes.

In the Arab world, where easel painting and sculpture in the round are colonial imports, the idea that prevailed was that to be authentic, art had to draw from the sources of one's own national history. While anchoring the work to the cultural context of their home countries, this aim also arose from the urge to remain close to the people. Popular subjects abounded, glorifying the lives of farmers and Bedouins, untainted by any foreign influence. Geometric forms and colors drawn from traditional ceramics and weaving constituted a rich source that emerged in certain paintings (Cockerel, by Shakir Hassan Al Said, 1954). Everyday objects, simple materials, and tattoos inspired the output of the Aouchem [Tattoo] group in Algeria from 1967 to 1972, for which Baya, among others, signed the manifesto. When Picasso began his collaboration with the Madoura ceramics studio in Vallauris in July 1947, where he met Baya, he revisited the ancient and popular Mediterranean traditions of Greece, Egypt, Etruria, Mesopotamia, Turkey, and, of course, the Arab-Andalusian region.

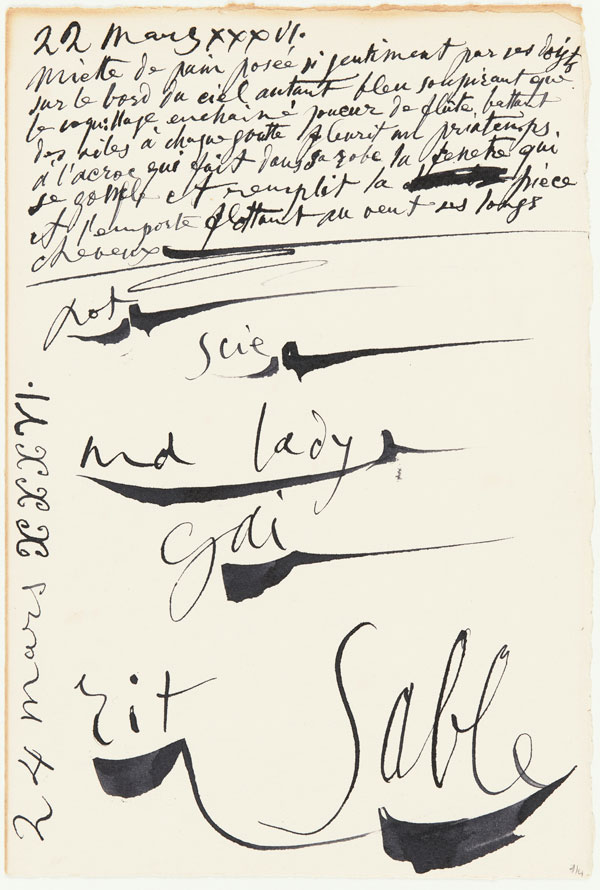

A similar twofold formal and cultural genealogy, both international and regional, was set forth in the unique Hurufiyya movement, for which Arabic calligraphy was one of the visual elements in a work of art. This approach was not only widespread in Iraq, where it had originally emerged, but also in Syria and the Maghreb, where it was at the heart of Mohammed Khadda's work. The Arab-Muslim world has always given a prominent role to poetry and writing. It was in the seventh century when the written transcription of the Quran under the caliphate of Uthman granted calligraphy and calligraphers their prominent status. In Muslim countries, writing transcends its usual function, becoming fully integrated in the artistic production of architectural ornamentation and miniatures. As early as 1949, the Iraqi artists Madiha Umar and Jamel Hammoudi, working in Washington and Paris respectively, linked Arabic calligraphy to abstraction in their quests. In 1971, the manifesto of the One Dimension Group, written by Shakir Hassan Al Said, theorized about its use and developed it under Sufi influence as an aesthetic of the line and of time. However, it was as a hallmark of Arab cultural authenticity and as the possibility of creating an artistic continuity between tradition and modernity, erasing the rupture of the colonial period, that the Hurufiyya emerged, all the way from Morocco and Egypt to Lebanon and Syria. Initially used as a visual element in the work of Dia Al-Azzawi, writing became a tool for reading the world in the Free Alphabets of Mohammed Khadda.

In a series of six articles published in the magazine Al-Hilal (March-December, nos. 3-12, 1968), titled "Souvenirs d'un artiste égyptien à Paris" [Memories of an Egyptian artist in Paris], Samir Rafi also reported on his decisive encounters, including one with Picasso in his studio. Rafi and Picasso had a rambling conversation about the common ground between the Egyptian spirit and the work of Alberto Giacometti and Henry Moore. In a letter to Gino Severini, dated June 1, 1960, Picasso wrote: "I've seen Rafi's latest pieces: an Egyptian who has got what it takes. His work is always powerful. He has become more Egyptian in Paris, just as Poussin became more French in Italy, and I'm more Spanish in France. One becomes oneself when one's away from home."

Some encounters never came about. For example, although they both knew the journalist Helène Parmelin and Édouard Pignon, the Algerian Mohammed Khadda and Picasso never actually met.

Coll. Ramzi & Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation, Beyrouth.

traduite en arabe par Nazar Salim en 1944.

Coll. Ruba Salim.

Musée national Picasso-Paris

Photo RMN-Grand Palais/ Musée national Picasso-Paris

Courtesy of Ramzi and Saeda Dalloul Art Foundation.

Summary

Summary