A rarely-discussed poetic vision: <br>Picasso's connection to the Arab-Andalusian world

After spending the summer of 1906 in Gósol, Picasso explored a new way of depicting the human figure which materialized in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Iberian sculpture and African art clearly came to the fore as the components of a hybrid figuration.

Alternately cubist, classical, surrealist, committed, and close to abstraction without yielding to it entirely, Picasso opened up new expressive possibilities to figuration by distorting, fragmenting, and multiplying the points of view on the objects and their scales.

By casting aside the rules of academic figuration, Arab modern artists perceived cubist distortions as sharing affinities with the altered figuration of Islamic art in which the artist had to distance himself clearly from divine creation.

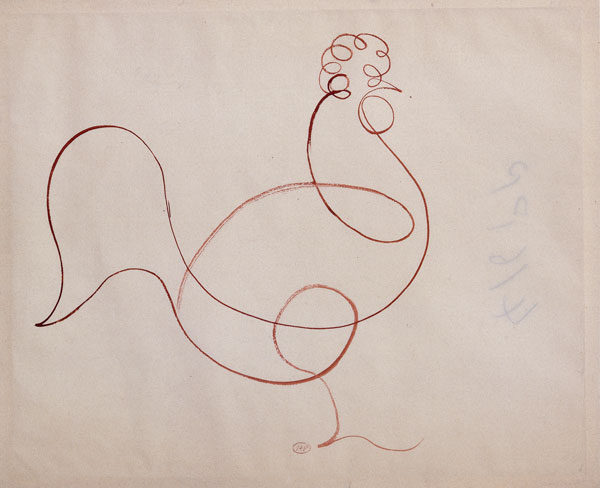

As early as 1905, Guillaume Apollinaire was the first to poetically highlight the potential connections between Picasso and the Arab East: "His unwavering pursuit of beauty has led him down many paths. He sees himself as more Latin morally and more Arab in terms of rhythm." In 1938, Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) claimed that "Picasso is a Spaniard, and a Spaniard can assimilate the Orient without imitating it," insisting on the affinity of his work with calligraphy, which, in the East, is intimately linked to painting and sculpture. In fact, continuous-line drawings and engravings abound in Picasso's work, revealing a deep mastery of calligraphic gestures and arabesques. The artist was immersed in the world of his writer friends, from Max Jacob to Paul Éluard, and he himself wrote hundreds of poems. His drafts show how for him, writing was a form of graphic expression. Le Corbusier was not mistaken when, in his attempt to move beyond Cubism in his purist manifesto Après le cubisme, written in 1918 jointly with Amédée Ozenfant, he criticized Cubism for being an art of arabesques and, as a result, too Oriental and by no means modern!

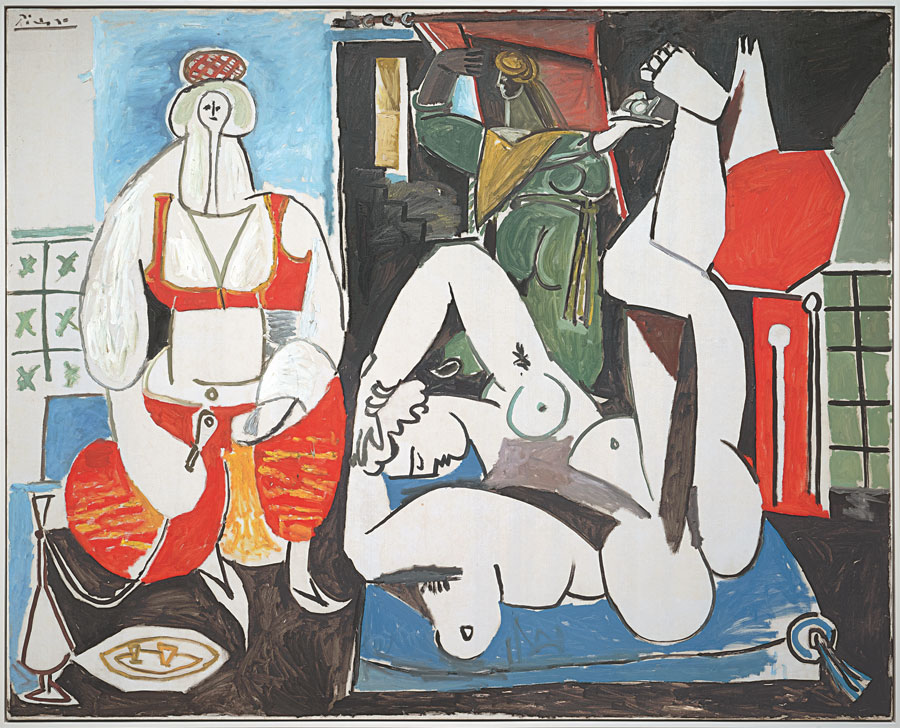

In the early twentieth century, two major exhibitions focused on the arts of Islam: one in 1903, held at the Marsan pavilion at the Louvre, and another in Munich in 1910, Masterpieces of Muhammadan Art. Picasso probably did not see them—unlike Matisse—nor did he travel extensively, but early on he looked to Ingres and Delacroix, as shown in his Harem of 1907, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Jacqueline in Turkish Costume, and especially his series devoted to Delacroix's Femmes d'Alger. Without sacrificing any exoticism, between December 1954 and February 1955, right after the outbreak of the Algerian war, Picasso produced fifteen paintings on this theme, as well as lithographs, preceded by about seventy drawings. This series also followed the recent death of Matisse, of whom Picasso said, "He left me his odalisques as a legacy." However, curiously, in the minds of Arab modern artists, Picasso was associated with the Arab-Andalusian world through the writings of a Frenchman, Eustache de Lorey (1875-1953), the Director of the French Institute of Archaeology and Arts of Islam in Damascus in the 1920s.

Summary

Summary