Georges Tabaraud and Pablo Picasso

The editor-in-chief of Le Patriote-Côte d'Azur,[1] former Resistance fighter, and PCF (French Communist Party) member Georges Tabaraud devoted his life to journalism. After working as a reporter for the Paris press before the war, he joined the Resistance before becoming the managing editor of Le Patriote shortly after the Liberation, and then its editor-in-chief until 1977. Meeting Pablo Picasso made a lasting impression on Tabaraud. As they became friends, the artist introduced the journalist to an understanding of pictorial art, its scope, and its history.

“It was thanks to the newspaper that I met Picasso. That encounter lit up my life,” he wrote years later in his memoir.[2]

Tabaraud and Picasso met one day in August 1946, after the artist had joined the PCF in 1944 and moved to the Côte d’Azur with his partner Françoise Gilot. “It was an extraordinary day for me, full of joy and admiration; I found the man that I was so nervous about meeting to show more fraternity, kindness, and warmth than I ever could have imagined. When I left, I thought that I would never dare to visit him again,” he recalled in his book.[3] But Picasso became fond of the young Party member who had risked his life with the Francs-Tireurs et Partisans armed resistance organization during the dark years of the Occupation, and who sought neither glory nor favoritism.

Picasso called him and invited him to his house; Georges Tabaraud then frequented the artist up until Picasso’s death in 1973. He “followed” the painter, partaking in the celebrations held to honor Picasso in Vallauris, or attesting to his activism in support of peace, particularly when he created his famous dove (1949); but also through the crises with the PCF, such as the affair concerning his portrait of Stalin (in 1953) or the doubts raised by the Red Army’s invasion of Hungary in 1956.

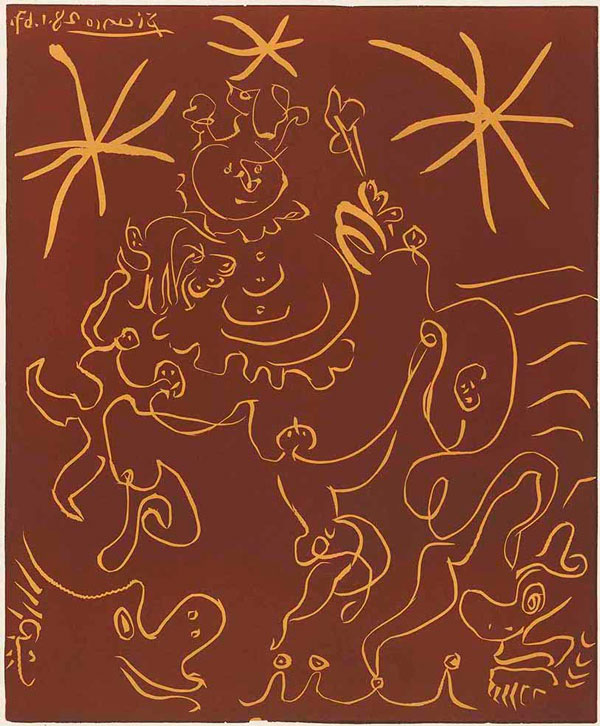

In a sense, Le Patriote became “Picasso’s newspaper,” particularly on the occasion of the Nice carnival: in 1951, as a gesture of friendship, Picasso drew the face of a jester king for the front page on that particular day of public rejoicing, and did so again every year from 1958 to 1967. The artist knew that the press was the main source of information for the French. His direct style was coupled with a sense of solidarity, a will to act and work together. Georges Tabaraud and Pablo Picasso joined forces in the good times and also in the bad, when the news took a turn for the worse.

On Carnival day, Le Patriote’s circulation reached its annual peak, particularly since Picasso also held a public signing of a special print run of the cover on fine paper; the sales proceeds helped to replenish the coffers of the daily, which later became a weekly. That was the artist’s way of helping the newspaper: it is a known fact that he willingly lent his name to the causes that were close to his heart.

Philippe Dagen wrote in Le Monde, in reference to Picasso’s contributions in the press: “The style is Picasso’s from that period: a flowing, highly synthetic line that highlights the axes of forms and the direction of movements in just a few strokes. Given its simplicity, it is easy to reproduce. Given its immediacy, it is suitable for publication. Given its intensity, it celebrates the spirit of the Resistance.”[4]

Under Georges Tabaraud, Le Patriote highly valued the political commitment of the intellectuals. The editorial staff regularly invited writers, artists, and graphic designers such as Nucéra, André Verdet, Michel Butor, Ernest Pignon-Ernest, and the illustrator Edmond Baudoin to contribute their pieces. As the newspaper’s editor-in-chief, taking sides for Algerian independence, Tabaraud had to face the violence of the far-right paramilitary OAS (Organisation Armée Secrète) in the 1960s, but nothing could deter this tireless activist.

Georges Tabaraud died in 2008, leaving a remarkable legacy of diverse contributions gathered from the best times of the communist press.

[1] The newspaper started out as an underground publication. At the time, it was called Le Patriote niçois. After the Liberation, in 1945 it became official and was renamed Le Patriote de Nice et du Sud-Est.

[2] Mes années Picasso, éditions Plon, 2002.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Philippe Dagen, Picasso, « Le journalisme et le Parti », Le Monde, February 19, 2000.

Summary

Summary