2022, Proust Year

When Marcel Proust (1871-1922) ventured into adulthood, he was an educated, well-to-do young man, in step with his era, who frequented high society, appreciated the arts, and was inspired by the spirit of the times. He loved the Impressionists, visited the Louvre and the exhibitions, and relied on his sharp curiosity to detect everything from the simplest to the superfluous, from the invisible detail to the most obvious of beauties. He wrote (illegible) notes in school notebooks. He feigned nonchalance while describing the dandyism of the moment, chronicling Paris life in the magazine Le Mensuel. His colorful characters portray the prevailing manners and customs, ranging from an attachment to the past to a fascination with the endless realm of possibilities and of radical audacities opening up as the new century approached. At the time when Proust began to write La Recherche, Picasso’s Cubism was born.

In Jean Santeuil, an anticipatory work begun in 1896 but not published until 1952, Proust revealed his ponderings: How does the passage of time affect a work of art? How does the overlap between the flow of individual destinies and the great current of History take place?

The succession of his parents' deaths between 1903 and 1905 left him inconsolable, but free. Free in his thoughts, in his homosexual tendencies, and in his views. Proust began writing La Recherche in 1909. He was one of the founders of contemporary literature; he renovated the genre and the way it was perceived, rendering it universal. He took pleasure in challenging received values, without breaking away from them entirely. His artistic tastes led him to seek out the art of the younger generation, yet without appropriating it openly. For him, art is a work in itself. The world is art. That is how he conceived his literature –as a work that one does not look at, but that one enters, with which one lives.

Picasso and Proust met on several occasions, and the writer was far from insensitive to the power of the painter’s works. Moreover, with his small, asthmatic body, Marcel Proust was struck by the ineffable charm of the artist “whom he found very handsome.”

Jacques Rivière mentioned Cubism in a letter he wrote to Proust in 1922, after reading the first volume of Sodome et Gomorrhe: “My dear Marcel, among the countless reflections of a general nature that you elicit, one thing, for example, which struck me for the first time was your relationship to the Cubist movement, your deep immersion in the contemporary aesthetic reality.” The inquisitive writer did in fact show an interest in Picasso’s modes of expression, even though he did at times have trouble deciphering their original meaning. Thus, as a faithful follower of the Ballets Russes performances, he did not fail to attend the opening of Parade with Jacques-Émile Blanche on May 18, 1917; there he discovered the sets and costumes designed by the artist he had met through Jean Cocteau.

In a letter written to Cocteau after the event, Marcel Proust was torn between acknowledgment of the beauty of Picasso’s gesture and incomprehension. However, he was sensitive to the painter’s radical forms of expression, which some historians believe to have found in Proust’s characters, when he superimposed the marks of time upon them, as in the the bal des têtes in Le Temps retrouvé (published in 1922, after his death). These overlaps are reminiscent of the painter’s figures and juxtaposed planes, seen from different angles, typical of the Cubist years and of Picasso’s formal explorations which led up to the Demoiselles d’Avignon.

The 100th anniversary of the writer's death offers us an opportunity to recall certain similarities between their respective aesthetic approaches.

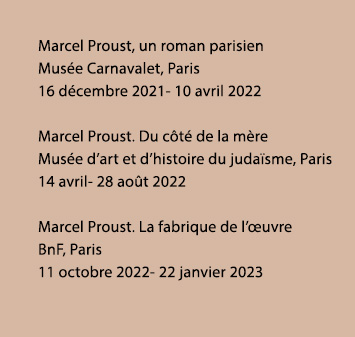

Illustration :

Les Baigneuses, musée national Picasso-Paris.

Photo RMN-Grand Palais/ musée national Picasso-Paris, Sylvie Chan-Liat.

Summary

Summary