Produced just two days after Maya's drawing, Seated Woman in a Grey Dress attests to this context and highlights the artist's outstanding creative vitality. This oil painted in a camaieu of grey and beige with unprecedented expressive power is diametrically opposed to the sweetness that emanates from the portrait of the child. Here the figure is scarcely identifiable; it looks as though several different models had merged into one. As Sidney Janis points out, Picasso did not work directly with a sitter, but painted his portraits from impressions and memories. Clearly the figure here evokes Dora Maar, the icon of the war years. Moreover, in his interviews with Francis Crémieux, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler said, "With Picasso, you could feel the war. Not that he painted monsters, as many people would have it. He always painted the women he loved. At the beginning of the war, it was Dora Maar. All the women he painted during that time looked like Dora Maar." (in Mes Galeries et mes peintres, Gallimard, 1961). However, this seated woman could also resemble Inès Sassier, a young woman of Italian descent whom Picasso had met in 1937 and hired as a maid. After her marriage in 1942, she and her husband moved into an apartment under the painter's studio at Grands Augustins. Picasso was very fond of Inès and trusted her entirely. She remained at his service until 1970, and he continued to paint portraits of her regularly. The wavy hair of the woman in a grey dress also suggests Françoise Gilot, who, although far from Paris at the time, continued to intrigue the artist. In her thesis Picasso and His Art During The German Occupation 1939-1944 (Stanford University Phd, 1985, p. 304), Mary Margaret Goggin goes as far as to view this woman in a grey dress as a synthesis of Françoise Gilot and Picasso himself, describing the left side of the face—more masculine, in the shadows, hairless—as the subtle presence of the artist, while the right side would be that of his new muse. This woman's face with two distinct profiles continues to be open to discussion: shadow and light, the artist and his muse, or a fading Dora Maar, about to surrender her place to Françoise?

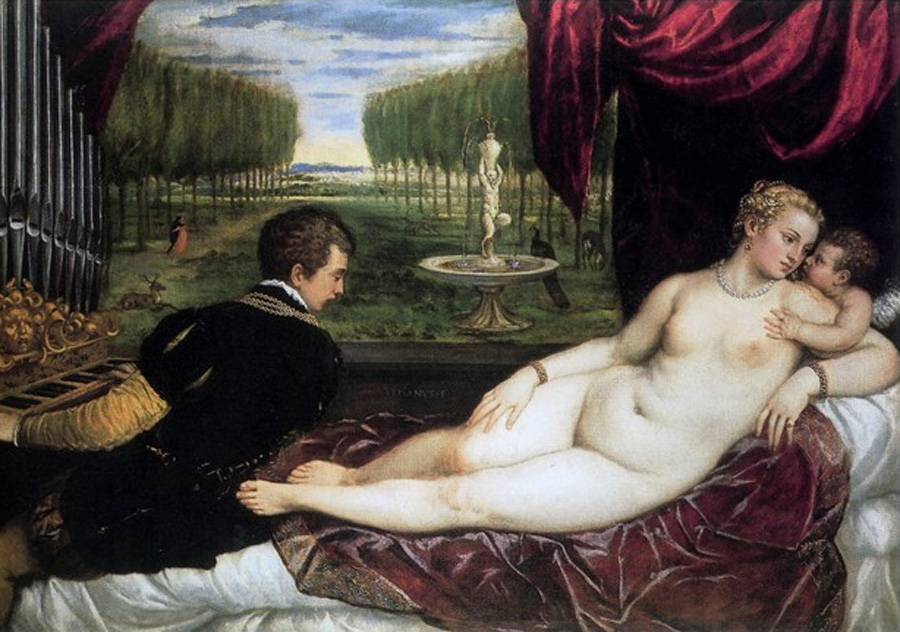

However, the matter at stake here is not so much to identify the model as to focus on the pictorial media used by the artist to express his revolt. After keeping a low profile throughout the entire period of the Occupation, Picasso needed to respond to a violent charge from Vlaminck on the artistic front. In June 1942, Vlaminck, embittered by not having met the same success as his rival, and anxious to settle old affairs with the leading figure in modern art, had published a violent editorial attacking the Spaniard in the cultural magazine Cœmedia. Using a series of gratuitous, base insults, he proclaimed Picasso "guilty of having dragged French painting down into a deadly impasse, into a state of indescribable confusion," and of having led it "from 1900 to 1930, to denial, impotence, and death." The affair was discussed at length in the art world, which was unanimously critical of Vlaminck's attitude. Given the sensitive political context, Picasso chose to remain silent and strike back with his art. That was when he produced the monumental composition L’Aubade (1942, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris) in which a seated woman serenades an odalisque lying on a bed. In this piece, Picasso returns to the classic theme of the serenade, and draws particular inspiration from Titian's Venus with an Organist and a Dog (1548), which he had seen on his visits to the Prado Museum. However, Picasso transposes the classical theme to the context of the war, of its horrors and its privations, turning the music room into a prison-like world. The angular forms of the composition and the dark tones of the background convey a strong sense of oppression. The pieces Picasso produced during the war, made up of lines that guide the eye through the compositions in the still lifes and the busts of women painted in cold, dark colors, reflect the artist’s sense of imprisonment.

Summary

Summary