Attendance and construction of the avant-gardes

The closeness of the early days gradually faded over time. Some suggest that they began to drift apart as a result of Apollinaire's dismay at Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. The art world considered the painting to be excessive, an opinion that Apollinaire seemed to share even though he never expressed it openly. He went from being genuinely fascinated by Picasso's work to feeling uneasy about it, to the extent that he stopped writing about the artist between 1906 and 1907. There was a long period of silence between the two, until Apollinaire took an interest in Braque's work and explorations, carried out jointly with Picasso. Picasso had started working along lines that were less disconcerting for the poet, and their relationship, untainted by the temporary lack of understanding in 1906, resumed a steady pace.

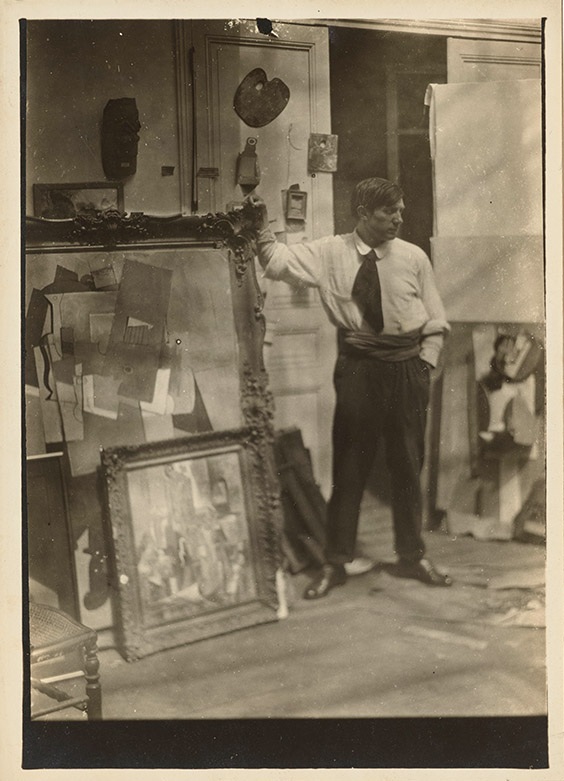

By then, Apollinaire had become a prolific and renowned art and literary critic. Nobody dreamed of questioning the soundness of his views. Close to the avant-garde, he was free to choose the subjects of his reviews and often proved to be discerning in his tastes, demonstrating the value of his judgment. Picasso acknowledged his ability: "Just look at Apollinaire. He knew nothing about painting, but he loved it when it was the real thing. Poets often get it right."[1] Apollinaire frequented the art circles, the salons and galleries, allowing Picasso, through his friend, to keep abreast of how the wind was blowing and how his work was being perceived. After the rise of what was referred to as "Cubism" in 1911, Apollinaire once again became a passionate advocate of Picasso's work, which he had not written about since Les Demoiselles, as mentioned above. The theft of the sculptures from the Louvre brought them together once and for all.[2] Both the poet and the artist were concerned about the consequences of this affair, given their foreign status[3] at a time when tolerance was in short supply. The poet's letters reveal the unenviable position of foreigners in France at the time. Apollinaire, who had spent several days in prison (from September 9 to 11, 1911), was particularly afraid of being deported. He confided about the matter to a friend, Toussaint Luca: "Find out where and how and under what conditions I could become a citizen. What would happen to me if I were deported from France?"[4]

[1] Pablo Picasso to André Malraux, quoted in André Malraux, La Tête d’obsidienne, Paris, Gallimard, 1974.

[2] After the Mona Lisa theft, Géry-Piéret, who had sold several Iberian sculptures also stolen from the museum to Apollinaire and Picasso, took one to Paris-Journal, demonstrating how easy it was to steal works from the museum. Three other missing sculptures had been sold through him to Picasso (two) and Apollinaire (one). Both friends found themselves unwillingly caught up in this unfortunate incident, and Apollinaire was even imprisoned for a time. All ended well for both artists, but Marie Laurencin put an end to her affair with the poet.

[3] In her book Un Étranger nommé Picasso, published by Fayard, 2021, Annie Cohen-Solal reveals that Picasso was "followed" by the French police intelligence service from 1901 onwards, completing a file (no. 76.664, foreign citizen file, Préfecture de Police, Direction de la Police Générale) containing his various requests and their responses.

[4] Pierre Daix, ibid, p. 27.

Summary

Summary