Which works of art left their mark on the artist? What are the places he visited, where he gathered knowledge and drew inspiration? In November 2016, the symposium organized in Venice by the Musée national Picasso-Paris, held in the majestic convent that now houses the Fondazione Giorgio Cini, attempted to address this vast subject. The two introductory lectures-a "Dadaist" contribution by Laurent Le Bon, the president of the Musée national Picasso in Paris, and an opening address by Luca Massimo Barbero, the director of the Istituto di Storia dell'Arte at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini-ushered in two sessions of speeches, exchanges, analyses and discussions.

Picasso looked, seized, appropriated. He was deeply and intimately interested in art history in the broadest sense of the term. He had the ability to recognize talent even in the smallest of everyday objects, but could also admire the mastery of great artists. Be they ancient sculptures, Florentine paintings or works by the Spanish masters, these artistic gestures nurtured, shaped, and accompanied him throughout his entire life.

At the symposium, Luigi Gallo highlighted ancient art, which Picasso so greatly admired and explored during his visit to Italy in 1917-particularly Pompeii-in the company of Leonide Massine and Jean Cocteau. Both in Naples and in Rome, he was also captivated by the folk art he observed in traditional crafts and, specifically in the local puppets. After returning from his trip, according to his grandson Bernard, he said: "Yes, I've been to Rome, but I haven't seen a thing. I just had a cup of coffee in front of the train station." According to Bernard Picasso, this statement reveals the artist's frustration with not managing to create as much as he would have liked to, given the many everyday impressions, as much in the streets as at the archeological sites and museums. According to Luigi Gallo and Pascale Picard, Picasso was overwhelmed by those "authentic" art forms, which he continued to seek in the ancient art halls of the Louvre. Jean-Louis Andral spoke of the ancient art displays at the museum in Antibes, designed by Romuald Dor de la Souchère, whom Picasso knew well.

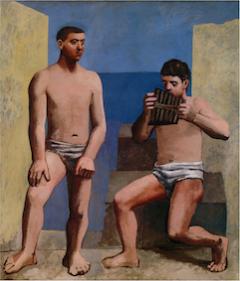

The artist's travels in Italy (from March 17 to late April 1917) led him to paint three canvases with a decorative scale that was undoubtedly inspired by his collaboration with Diaghilev's Ballets Russes for the sets of Parade. However, after producing these pieces, Picasso spent a long time recapturing the movements, expressions and fleeting impressions he had perceived during that journey.

This stay in Italy was the point of departure for an ambitious quest that was analyzed at the symposium. At the initiative of the Musée national Picasso in Paris, it will be extended for two years (2017-19). Sixty institutions will be programming Picasso exhibitions, linking his work to the collections held in participating venues-hence the originality of the concept. These perspectives, dialogues, discussions, and new research studies are aimed at reconsidering his output and placing Picasso back at the center of art history.

In Cyprus, Greece, France, Italy, Spain, and Morocco, the program will show the different facets of Picasso's production. This unprecedented cultural tour of Mediterranean countries will show the specificities of the artist's work according to the different places where he lived, his personal and political concerns, and the people he met along the way.

In addition, the event will provide the opportunity to gather the available research and provide historians with a database that will include oral memories about the artist. This archive, updated regularly, will be an excellent source for further research.

An overarching communication program and a common label will enable the projects to be compiled in a publication. The program will include a website providing access to all the available information.

Summary

Summary