David Douglas Duncan, born on January 23, 1916, will be 101 in 2017. After spending almost fifty years in Provence, the photographer speaks with elegance and simplicity. Endowed with an extraordinary memory, he is pleased to give us his account of the major events of the 20th century and the people who made a mark on his life. In his books and exhibitions he bears witness to particularly difficult times, such as World War II and the conflicts in Korea and Vietnam. In fact, David Douglas Duncan was a war photographer for many years. First as a "mere" witness and later as an officer in the Marines, he eventually became a reporter. Experiencing war as it unfolded in daily life, Duncan shows the soldiers' devastated humanity, their fear, their sorrow, their pain and their suffering, but also their hope. He reveals the solidarity, the mutual support inside the battalions. Duncan published his photo essays in Life magazine for ten years. After that, he began focusing on his own books, seeking greater freedom to express himself and voice his views. His best-known work, I protest!, published by New American Library in 1968, was an attack on the government, whose militarism and methods he opposed.

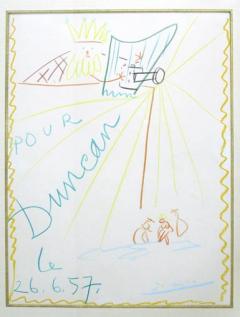

One day in 1956, David Douglas Duncan rang the bell at the gate of La Californie, in Cannes, where Picasso lived. He explained that he would like to meet the painter and had been sent by their mutual friend Robert Capa, who had died prematurely in 1954 while covering the war in Indochina. The gate was opened and "DDD," as he was known, discovered the painter... in the bathtub. Startled and amused, he asked Picasso if he could go get his camera from the car. That was the beginning of a long friendship that lasted up to the artist's death. "I became close to the entire family. They accepted me like a mosquito," he likes to tell journalists when asked about their relationship.

Picasso was delighted to welcome David Douglas Duncan when he arrived in his Mercedes 300 SL with gull-wing doors. He would "just be stopping in for a minute," and would end up staying six weeks. "The painter paints and the photographer takes photographs." That is how the Maestro-as Duncan referred to him- defined their respective activities. "I was neither an art historian nor a painter, a dealer nor a conservator. I wasn't the world's greatest photographer, either. But I was the only one who stuck around, day after day." DDD is undoubtedly the photographer who best captured the artist's everyday life, because his affection for the couple was reciprocated and straightforward. In addition, he was particularly unobtrusive, going as far as sending his Leica to Japan to have it equipped with a silent shutter. Picasso never intervened in Duncan's choice of photographs for the seven books he published about the artist. Throughout their pages, we see the painter working, thinking, enjoying himself, dancing, wondering, laughing, deliberating, and kissing his wife and his children. Duncan followed his frenzied activity, bearing witness to the generosity of an artist who was always happy to entertain his friends and share his table. Close to 5,000 negatives were the outcome of this exchange.

David Douglas Duncan's sensitive body of work on Picasso is precious and unique because it provides essential clues for understanding the painter's creative process. We discover paintings that Picasso never showed during his lifetime and an unusual way of working. We see the artist in the midst of his carefully organized chaos. We are moved by his intimate moments and by the reassuring presence of his wife Jacqueline.

In a film produced in 2007 and shown during a seminar held by National Geographic magazine in 2008, Duncan explains: "There is no decisive moment, life is a flux. Who knows what happened right before and right after I took my picture? In my photographs, I created a world, but I never captured the face of life itself. I just got close to it. I did the best I could."

Often shown and published, the photographer's archives are housed at the Harry Ranson Center, at The University of Texas at Austin.

Summary

Summary