Going beyond the obviousness of the readable, Picasso’s insertion into the history of art

Picasso was always a firm advocate of art history, celebrating the painting of the past and the works of other cultures in many ways and more than any other artist. His relationship to the art of the past —from prehistory to the great masters or to the artistic output of non-European cultures— reveal his talent for appropriating, reinventing, and distorting references to a universal language. He drew from these artistic affinities with a will to upend established values through a liberating dialogue with his departed peers.

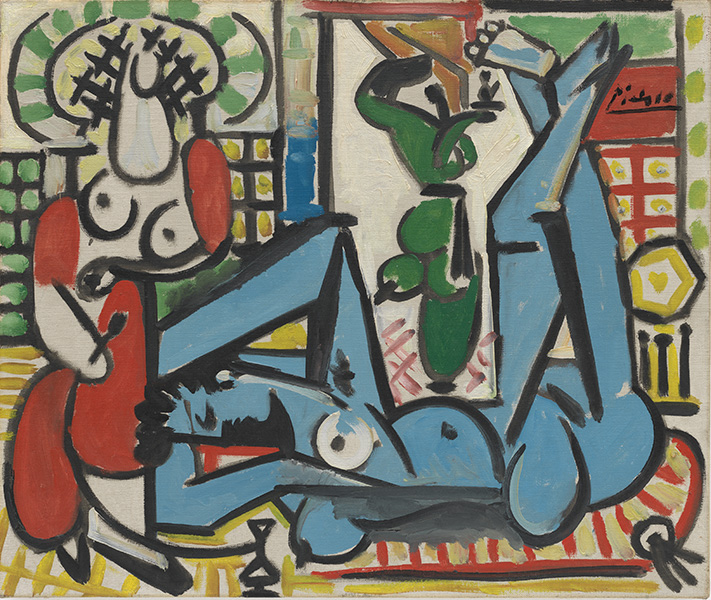

His unique position in 20th-century art history was partly due to his relationship with the masters and to his urge to enter the lineage of great Western painting. Between tradition and avant-garde, technical mastery and innovation, stylistic rebellion and tributes to the past, the destruction of established codes and poetic wanderlust, this iconoclastic artist traversed the 20th century leaving a lasting mark on the history of art. A desire to build bridges with the masters took hold in his artistic approach. When he began working on the Femmes d’Alger series, sceptics claimed they detected an absence of style, to which Picasso responded: "Basically, I don't have a style. A style locks a painter into a single vision, a single technique, a single formula."[1] His deadpan reply showed the extent to which he disregarded critics, asserting his desire to venture beyond the evidence of the obvious to pursue his own formal quest. Some even referred to him as "cannibalistic" on account of his radical, assertive approach.

Picasso used lines and colors symbolizing modernity to express the events in life itself, ranging from the most intimate experiences to his indignation at the absurdity of the world and of war. He made use of everything in his work, keeping an eye on others, his mind always alert, and showing a degree of curiosity as precise as it was insatiable for all aesthetic inventions and techniques, from Egyptian statuary to Surrealist collages. His fascination with the paintings of the old masters and the treasures they revealed never wavered. He seized everything that came his way, translating trends and thoughts. He sought utter freedom of gesture. He found inspiration in the origins of art, in turn producing major works himself. His output is full of dazzling and comical moments. He left his mark on the history and the perception of painting. Nevertheless, at the time art critics and historians had their doubts about Picasso's "stylistic performances." According to Claude Levi-Strauss, "rather than contributing an original message, in a sense his work indulges in grinding up the code of painting."[2]

Summary

Summary