Femmes d'Alger, between appropriation and fruitful imagination

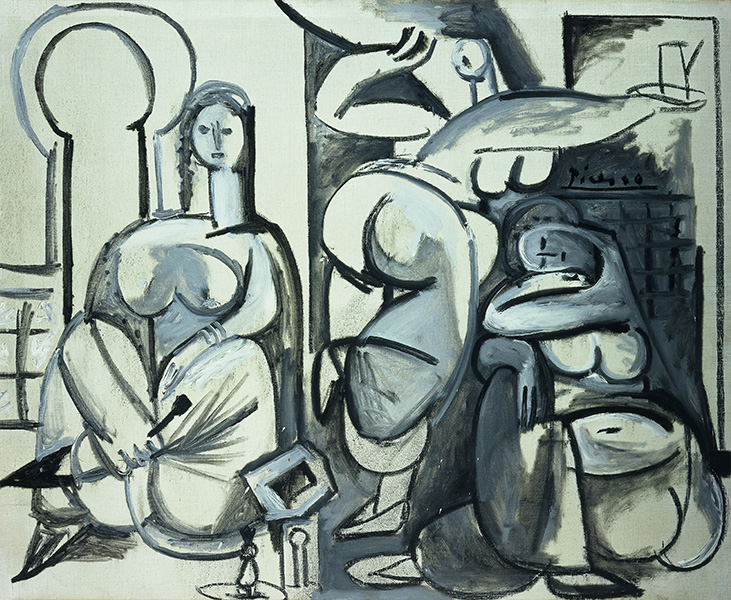

The observant artist was interested in this painting for the mysterious relationships between the depicted figures, which he chose to reinterpret. Picasso used the version from the Louvre as his starting point, while also taking into account the painting from the Montpellier museum. "For Picasso, art ranges from external inspiration to an intimate need [...] but he needs these two opposite poles. To replace the first pole with Delacroix is to take unexpected risks. [...] In the first two pieces, Picasso only uses the right side of Delacroix's painting, undressing the torso of the woman who resembles Jaqueline [...] The servant moves into the background. Picasso tightens up the rhythms, highlighting them as if to disrupt the serenity of the secluded setting [...]. The second version simplifies and pares down the scene. The canvas is reduced to a scale of greys. The third version, painted two weeks later, riles up the entire composition, reintroducing a third hieratic woman in the center [...] and flips over the sleeping woman, now entirely naked and raising her legs over the polygonal side table borrowed from the Montpellier painting."[1] The tone changes in the fourth version, with the woman sitting on the floor. The fifth version (Version E), dated January 16, focuses primarily on the sleeping figure. In version F, dated January 17, "the woman keeping watch has the round face and the breasts of Françoise [Gilot]."[2] In subsequent versions, in a geometric or more pared-down vein, we find watchful, heavy-breasted women sitting, crouching, or sleeping, with graceful forms and airy poses, depicted either in generous colors or in shades of grey (as in Version M, February 11, 1955); busier (such as Version C, December 28, 1954) or sparer versions (Version H, January 24, 1955). Françoise's face appears (in Version O, February 14, 1955). Some of the gestures suggest the Demoiselles d'Avignon (Version O, February 14, 1955). The tribute becomes intimate, revealing Picasso's inner world. The painter borrows the subject and the style, which he revisits in the historical context in which he feels the need to anchor himself through quotation, while never settling into an established trend.

The series sought the dazzling amplification enabled by the power of colors and forms. Picasso was passionate about his explorations. He was constantly inventing, seeking to bring his subjects to life along with the space surrounding them. "The three series based on Delacroix, Velázquez, and Manet, produced in the 1950s, allowed Picasso to tackle compositions with multiple figures, conveying interior settings (harems, studios), and an outdoor scene; above all, they allowed him to settle scores with paintings he had long admired, with key masterpieces in the history of art. Picasso broke into the pictorial space of others, as if trespassing."[3] He produced his different variations with perseverance, discovering possible variations in each one of his versions, greedily appropriating the work of his predecessor, drawing inspiration from it while entirely recasting the roles and status of the depicted characters.

Summary

Summary