Picasso's interest in Bergsonism ? the influence of Max Jacob

The first chapters of my thesis are devoted to the history of the subject. The following chapters address the study of Picasso's artistic approach during his analytical cubist period, as well as the analysis of certain works whose selection aims to prove the plausibility of my hypotheses: Picasso's interest in Bergsonism. Through its formal landmarks and its key stylistic elements, I believe this body of works offers the hermeneutic framework within which Bergsonian concepts acquire meaning. They are, in a sense, spontaneous constructions that seek to answer questions about life and about consciousness. Picasso has only one resource: intuition.

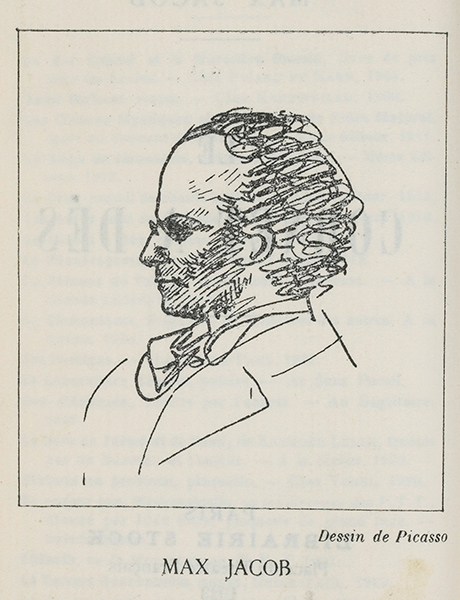

It was especially through Max Jacob, and through the interpretation that he offers, that this concept made its way into Picasso's art. The term intuition holds a place of its own within the poet's vocabulary: for him, it replaces the notion of artistic inspiration. Max encouraged Picasso and his young artist friends to develop their own inner lives. For Jacob, inner life was a method–a method that instead of defining things, made it possibe to experience them.[1]

Considered as analogous to an inner life, this method was so important in his view that he proposed to build a school for its promotion. But not just any school: a school of art!: “I will open up a school of inner life and I will post a sign on the door: School of Art”, he wrote in his advice to young poets.[2]

Max was not only Picasso's first French friend; he also generously shared the broad scope of his culture with the artist. In addition, they lived alongside each other for twenty years, in a more solid friendship than many are willing to acknowledge, and which did not exempt them from all the “battles”, the great moments of a new form of art of which they liked to see themselves as the leaders, beginning with cubism. For Max, Picasso was the genius: the one with the courage to reconsider everything once he had explored a given path long enough. Fascinated by Max's philosophical and literary knowledge, by his obstinate research and his bulimic reading, Picasso also shared a passion for symbolist poetry with him that drew its inspiration from Bergsonian philosophy. Jean Cocteau recalled the young ones–Picasso, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, running around Montmarte shouting “Long Live Rimbaud! Down with Laforgue!”[3]

It was through the metaphysician Louis Dugas, who was his philosophy teacher, that Max Jacob discovered Bergson's early writings. In his biographical work La Défense de Tartufe, the poet recalls the enthusiasm with which he copied Bergson's theories in a pink-covered notebook while he listened to his father's embroidery workers singing Breton songs.[4] According to Max Jacob, the three most defining characters in that period were: Freud, whose discovery of the keys to sexuality opened up the mysteries of the unconscious mind; Bergson, with les premières Irradiations de la Matière@, and Gustave le Bon.[5]

[1] Max Jacob quoted in Pierre Andreu, Max Jacob. Conversions célèbres, Wesmael-Chariler, Paris, 1961, p. 103.

[2] Max Jacob, Conseils à un jeune poète. Conseils à un étudiant (Advice to a Young Poet), Gallimard, Paris, 1980, p. 29.

[3] Jean Cocteau, La difficulté d’être (The Difficulty of Being), Paris, Paul Morihein, 1947, pp. 174-175.

[4] Max Jacob, La Défense de Tartufe : Extases, remords, visions, prières, poèmes et méditations d’un Juif converti (1919), new edition, Paris, Gallimard, 1964, pp. 290-291.

[5] Max Jacob, Chroniques des temps héroïques (1936), Paris, Louis Broder, 1956.

Summary

Summary