A more spiritual stage of creative production for Picasso

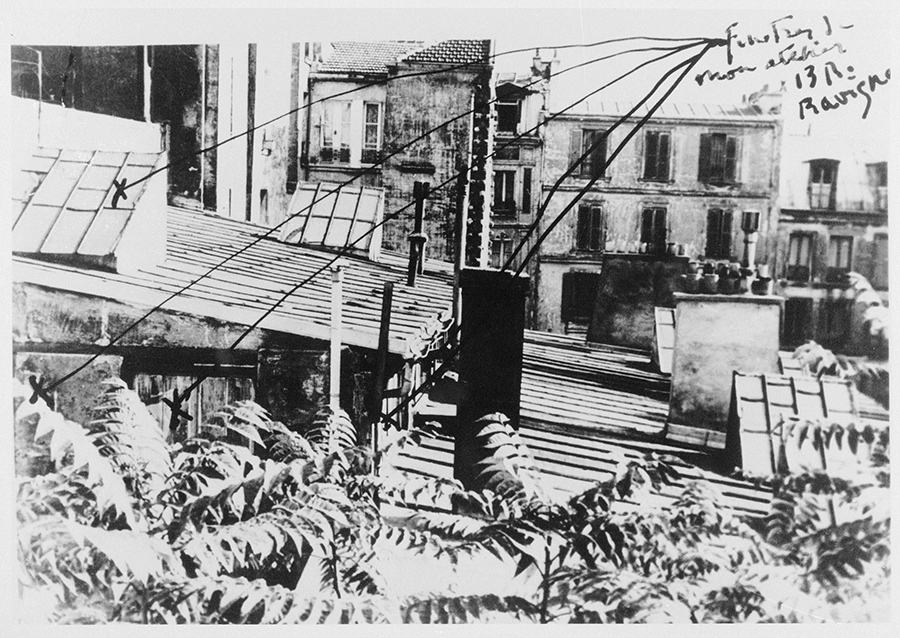

After meeting Picasso at Ambroise Vollard's gallery in June 1901,[1] Max Jacob began to exert an increasingly important role in the artist's orientation towards a more philosophical and spiritual form of art of which Bergson was the undisputed instigator. This philosopher was essentially the source of inspiration for certain creative forces and leading figures in the most innovative movements, figures who Picasso met and frequented through Max Jacob. Jacob was a great help to Picasso in the early years,[2] sharing his room on Boulevard Voltaire with the artist in 1903 and thus allowing him to concentrate on his art. In 1904, after Picasso moved to Montmartre, into a ramshackle building knicknamed Le Bateau Lavoir by Max, the poet tried to move closer to him and rented a small room on 7 Rue Ravignan. He visited the painter's studio every day. Together with the young art dealer Henry Kahnweiller, he was the only person who truly understood the manifesto-painting of cubism that Max named Les demoiselles d'Avignon, describing it as the first exorcism painting.[3]

It was the beginning of a more spiritual stage of creative production from which Picasso would later distance himself, given his concern about staying in touch with concrete, objective reality.

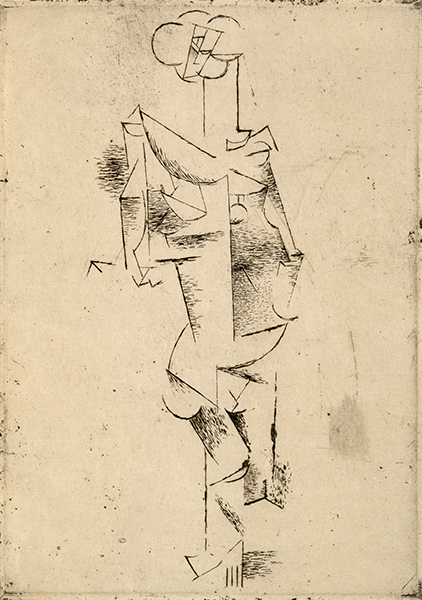

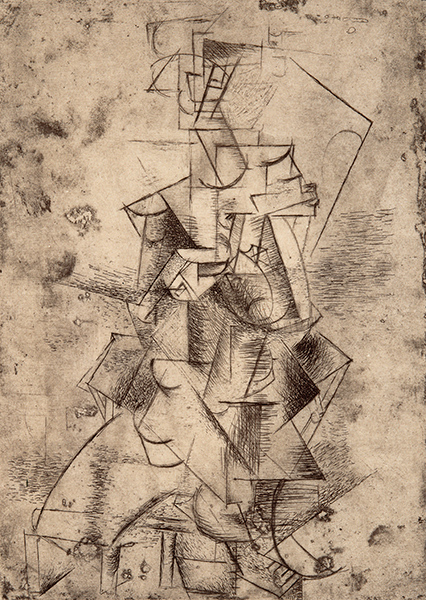

The intense communion that bound Picasso to the poet during his mystical venture and up until the appearance of the burlesque and mystical frère Matorel works of 1912, and of the manuscript of the novel Le terrain Bouchaballe–for which Max consulted Picasso about the final choice of a title–, left a deep mark on the analytical years of cubism. That was around the time of Max's “conversion” to catholicism. In fact, it was a time when the Catholic Church registered a series of spectacular conversions, beginning with those of certain symbolist poets acclaimed by the young Picasso–Max Jacob, Apollinaire[4], and Verlaine, who converted in 1874–and followed by the philosophers Jacques and Raïssa Maritain, who belonged to Max and Picasso's circle. The publication of two works by Bergson, Les Données immédiates (Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness) in 1889 and Matière et mémoire (Matter and Memory) in 1896 contributed to a process of shifts of consciousness that made it possible to justify the waves of conversions to Catholicism. In the case of Max Jacob, his conversion was clearly anticipated by his readings of Bergson's philosophical texts and of major esoterical and even astrological works at the Bibliothèque Nationale–under the curious eye of Guillaume Apollinaire. The “Christic vision”, that “sacred image” that appeared on his wall and that Max Jacob claims occurred sometime between 1909 and 1912, determined him to write and publish Saint Matorel with Kahnweiler in 1911, and Picasso, whose “cubic oddities” had begun to seriously intrigue the critics, was entrusted with illustrating the publication.

[1] V. Jeanine Warnod, Le Bateau Lavoir, Paris, Presses de la Connaissance, 1975, p. 49

[2] Paul Yaki, Francis Carco (préf.), Le Montmartre de nos vingt ans, Paris, Librairie Tallandier, 1933, p. 121.

[3] André Malraux reports in La Tête d’obsidienne (Paris, 1974) that Picasso confessed to him that it was “his first exorcism painting.”

[4] See Jean Cocteau, La difficulté d’être (The Difficulty of Being), Paris, Paul Morihein, 1947, pp. 174-75.

Summary

Summary