With Communist Party, “I am again among my brothers…”

homeland! I have always been an exile. While I wait for the time when Spain can take me back again, the Communist Party has opened its arms to me and in it I find again all my friends [...] and so many of the beautiful faces of the insurgents that I saw in those August days at the barricades in Paris. I am again among my brothers."[1]

Picasso became the most outstanding new member in a PCF national recruitment campaign after the Party became legal again. In the absence of Maurice Thorez, who was still in the USSR, the new militant was welcomed with honors by Marcel Cachin and Jacques Duclos. Paul Eluard, Aragon, and Pierre Villon, the leader of the Front National, were also present. Although the war was not yet over, on October 5, 1944, l’Humanité devoted half of its front page to the great painter's adherence to the PCF.

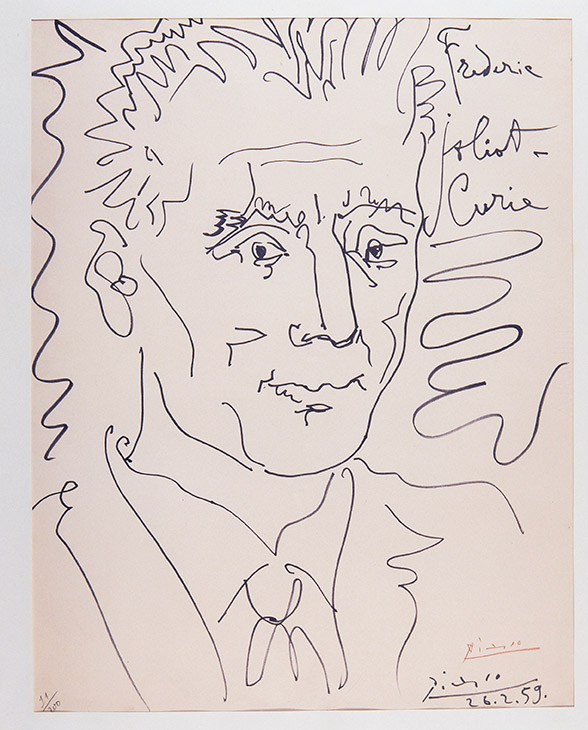

"Unprecedented Promise," by Paul Eluard. "We are living in a time of black and white, where, now that the horror has begun to recede, unprecedented promises are appearing all over, lightening up the future. The best of our men have fought against the hardships that have befallen our country: Joliot-Curie, Langevin, Francis Jourdain, and Picasso have put their entire lives at the service of man. They have stood resolutely on the side of the workers and peasants. Today I saw Pablo Picasso and Marcel Cachin embrace. And I witnessed nobility of mind and heart when I heard Picasso thank the French people by joining its greatest party: that of the executed." On October 29, L’Humanité also reprinted Picasso's interview from the American magazine. The day before the first legal PCF congress since 1937, held on May 23, 1945, Picasso painted a portrait of Maurice Thorez, its Secretary General.

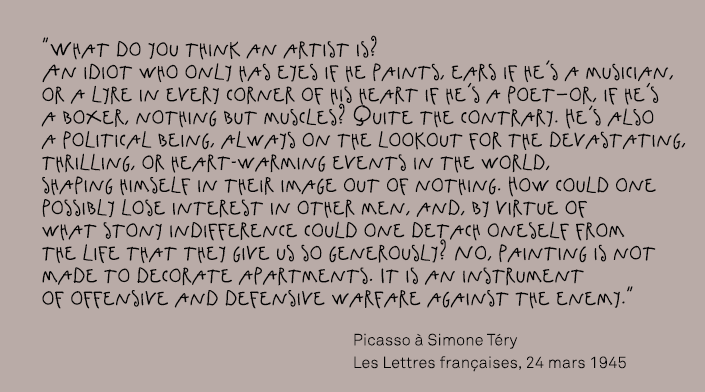

Picasso explained his position clearly to the journalist and novelist Simone Téry (who had been a war correspondent on the Spanish Republican side) in an interview for the March 24, 1945 issue of Les Lettres françaises (the title of the article was "Picasso n’est pas officier dans l’Armée française," [Picasso is not an officer in the French army]). "What do you think an artist is? An idiot who only has eyes if he paints, ears if he's a musician, or a lyre in every corner of his heart if he's a poet—or, if he's a boxer, nothing but muscles? Quite the contrary. He's also a political being, always on the lookout for the devastating, thrilling, or heart-warming events in the world, shaping himself in their image out of nothing. How could one possibly lose interest in other men, and, by virtue of what stony indifference could one detach oneself from the life that they give us so generously? No, painting is not made to decorate apartments. It is an instrument of offensive and defensive warfare against the enemy."[2]

However, the issue is more complex. The image of the enemy is constructed through the accusation, or even the certainty, that the opponent stands out on account of its brutality and the "atrocities" it has committed. For each side, war is a matter of "civilization" versus "savagery." This was particularly true during the Second World War, whose protagonists willingly reported on the suffering of the population, the indiscriminate violence, and the danger of the enemy camp. Through his painting, Picasso took note, denounced, challenged his contemporaries, and shared his view of the conflict with them.

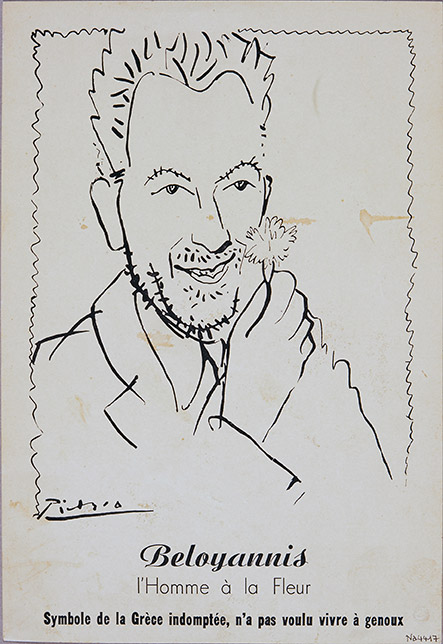

After producing The Charnel House,[3] his tribute to the victims of the Nazis, Picasso attended the fiftieth birthday celebration for Dolores Ibárruri, "La Pasionaria," on December 9, 1945 in Toulouse, jointly with his friend Jaime Sabartés. In the Art et résistance exhibition organized by the PCF the following February with pieces by artists who shared the Party's views, Picasso's works were present, but without his more abstract paintings. In Antibes, in 1947, Picasso happened to run into André Breton, who asked him to justify his reasons for joining the Party. "My opinions are the result of my experience," answered Picasso; "Personally, I value friendship above political differences." Breton refused to include Picasso in the international Surrealism exhibition he was preparing for the Galerie Maeght in the spring of 1947. Picasso's works were not in line with the aesthetics of social realism, either—the art embodied by André Fougeron and advocated by Aragon, whose aesthetic opinions were strictly orthodox at the time.

Summary

Summary