Painting peace, in the midst of armed conflict

Painting peace, in the midst of armed conflict

In 1948, with the poet André Césaire, among others, Picasso participated in the World Congress of Intellectuals in Defense of Peace, held in Wroclaw. He called for the release of his friend Pablo Neruda, who was persecuted in Chile at the time. In his memoir,[1] Pierre Daix describes Picasso—who had just taken his first airplane flight—having trouble yielding to the discipline of the communist movement, and offering a shirtless toast before a group of stunned bureaucrats.

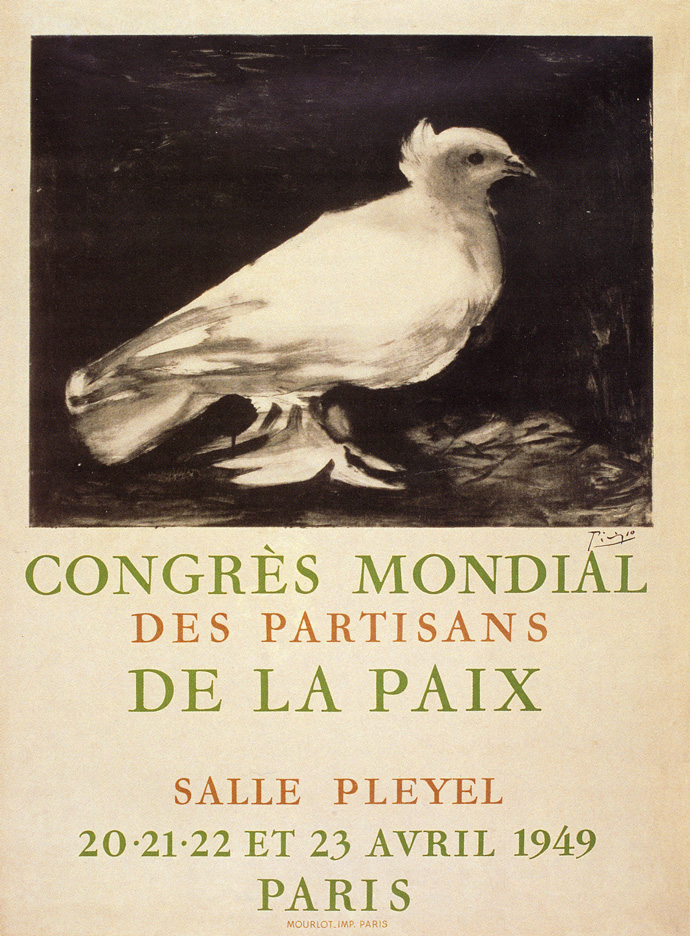

In the spring of 1949, Aragon asked Picasso to design the poster for the upcoming World Peace Congress in Paris. In his studio on Grands-Augustins, Picasso showed Aragon a pile of lithograph proofs and asked him to choose one. As we know, Aragon chose the dove. According to Geneviève Laporte, the painter made an ironic comment: "Poor Aragon... his dove is really a pigeon! He doesn't know the first thing about pigeons. The myth of the sweet dove, what a joke! No animal is as cruel as a pigeon. [¼] What a symbol for peace!"

Maurice Thorez suffered a stroke in October 1950 that left him unable to work until April 1953. This long absence of one of his supporters, the man who had defended him against the accusations of "decadent formalism," weakened Picasso's position, and André Fougeron became the official painter for the PCF. Another competitor was Fernand Léger, who had also joined the Communist Party when he returned to France. Léger delved into his Construction Workers series, which the Party considered an adequate response to its requirements for artists to practice art that supported working-class values. Construction Workers (to which Paul Eluard dedicated a poem) was shown in June 1951 at the Maison de la Pensée française. Fernand Léger wanted to donate his large Construction Workers painting to the General Confederation of Labor, but the union rejected his gift. The Party's campaign to impose Fougeron, carried out by Aragon in a series of articles on Soviet painting in Les Lettres françaises (no. 398-408, January through April 1952), caused some tension. Picasso and Léger publicly stated their negative opinion of official Soviet painting.

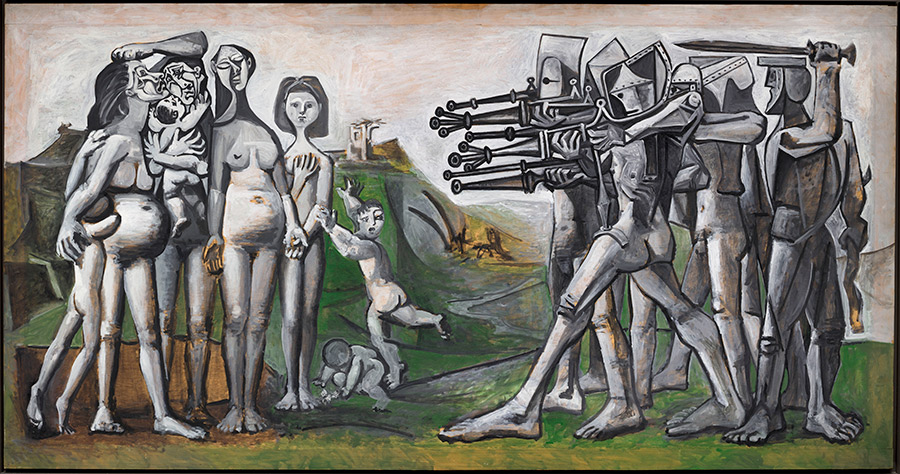

It was within this context that Picasso painted Massacre in Korea,[2] his most explicitly political painting, in January 1951. The piece, inspired by the massacre on the No Gun Ri Bridge, where 400 Korean civilians were murdered in July 1950, drew upon Goya's El Tres de Mayo en Madrid (1814) and Poussin's Le Massacre des innocents (1625-1632). "What emerges, however," wrote Pierre Daix, "is his most intimate reaction as a father facing this far-away war. He creates a science fiction scene: a group of children and pregnant women facing robot-like warriors." Yet his Massacre in Korea failed to move the Party members.

The party line further developed in a statement by Auguste Lecœur, the secretary for the PCF organization at the time. He compared Picasso with the communist and realist painter Fougeron, who he claimed "fights from his position as a communist," whereas Picasso, in his view, "fights from his position as a partisan of peace." A first-class burial, as Pierre Daix noted.[3]

Picasso produced a luxury illustrated book, Le Visage de la Paix, to raise funds for the Party, with a text by Eluard:

"I know all the places where the dove dwells.

Its most natural home is the mind of man."

He participated in a major PCF campaign to save the Greek leader Beloyannis by drawing The Man with the Carnation. Despite these efforts, Beloyannis was executed along with three of his KKK comrades at dawn on March 30, 1952.

At the height of the Cold War, Picasso produced other doves for the annual Peace Councils. For the second Council to be held in Sheffield, England, in November 1950, Picasso etched another dove, but this time in flight. The event, which Picasso was supposed to attend, encountered several setbacks: the British authorities denied visas to many delegates and the Council had to be moved to Warsaw. The number of delegates in Sheffield dropped from 2000 to 500, most of them British. For the 1952 Council in Vienna, Picasso drew a rainbow, after a bolder project had been turned down by the organizers.

In the 1950s, Picasso was a regular contributor to l'Humanité. In addition to his peace-themed drawings, his tributes to Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Henri Martin, Beloyannis, Joliot-Curie, and Paul Langevin appeared on the front page. Picasso also produced drawings for local Communist Party newspapers such as le Patriote, published by the Communist Party of Nice and Southeastern France, and other associated publications such as Combat pour la paix.[4]

Summary

Summary