Act, paint symbols and promote dissemination

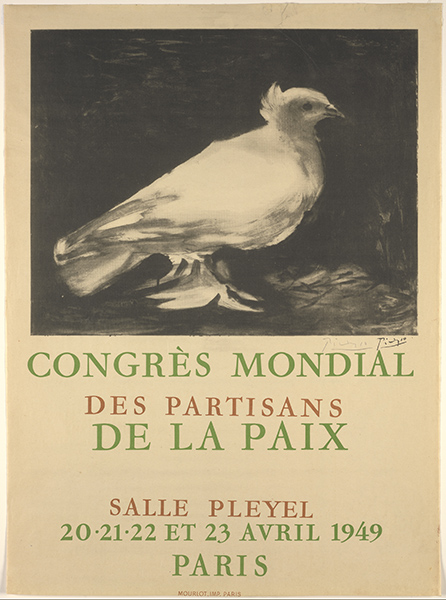

After the Second World War, Picasso continued his efforts to support the Spaniards who had stayed in France. He gave works and large sums of money. He participated in exhibitions that gathered exiled artists, and his output, by his own admission, was marked by the war. He created specific pieces whose symbols became famous throughout the world, such as his Dove, the poster he designed in 1949 for the World Congress of Partisans of Peace held in Paris from April 20 to 25 at the Salle Pleyel. [1] Presided over by Frédéric Joliot-Curie, it brought together writers such as Eluard and close to forty artists, including Rouault, Léger, Fougeron, Pignon, and Picasso.

Picasso was careful to create clear lines that were easy to reproduce in large numbers, since these works – rallying calls, in a sense – were intended for distribution to a wide audience. For the artist, creating them was almost a philosophical endeavor. His skill was serving a just cause, the hope for a better world, and readily supported intellectual movements rooted in political struggle. He worked his lines and strokes with sharp precision to wage merciless war against his fascist enemies. His posters nourished his spirit of revolutionary commitment and recalled his heritage and roots, such as Amnistía, produced for the Comité national d'aide aux victimes du franquisme in 1959. The bird trapped behind bars seems to be able to take flight.

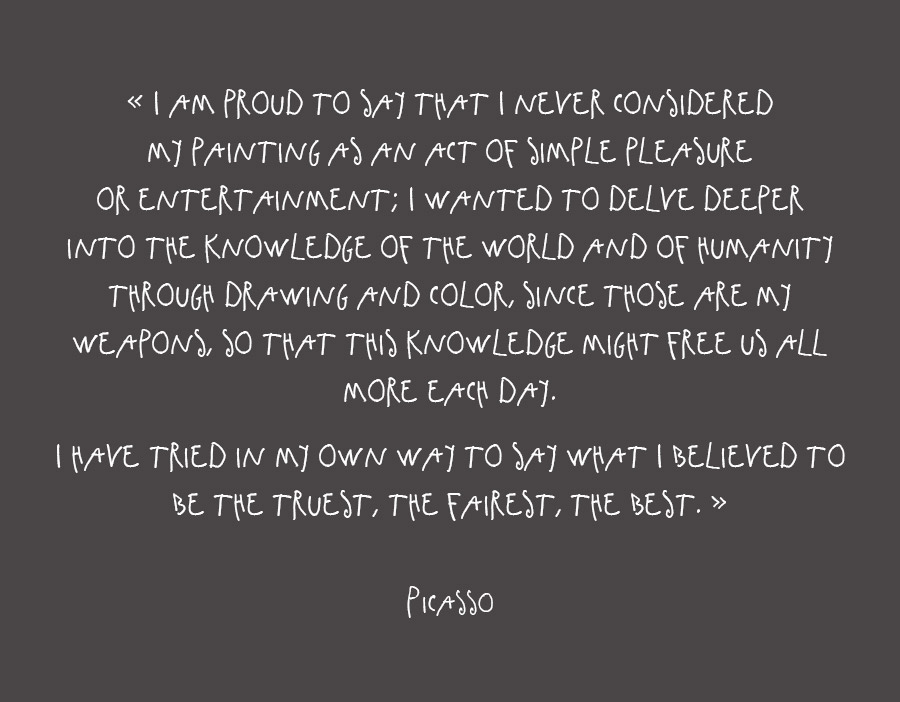

When he received the team from L’Humanité that had went to interview him when he joined the French Communist Party in 1944, he insisted: “I am proud to say that I never considered my painting as an act of simple pleasure or entertainment; I wanted to delve deeper into the knowledge of the world and of humanity through drawing and color, since those are my weapons, so that this knowledge might free us all more each day. I have tried in my own way to say what I believed to be the truest, the fairest, the best.”[2]

Lydie Salvayre, the winner of the 2014 Goncourt Prize for her novel Pas pleurer (published in English as Cry, Mother Spain) and herself the daughter of Spanish refugees, evokes the country and the events as her parents experienced them in the pages of her novels. She condenses into a few sentences some of the dilemmas inherent to forced displacement, the status of foreigners in a host country: “some people are foreign due to their language and nationality; others are foreign due to their inability to adapt to a different set of social codes.”[3]

According to Jean-Maurice Rouquette, the former director of the Musée Reattu in Arles, “Picasso came to the corridas and met his friends at the Place du Forum, where he joined the Spaniards who had escaped the Franco regime, in a sort of mutually supportive fraternity. He brought them engravings, which he signed and gave to them, ensuring their livelihood. Then he would invite the friends of his friends as well, and they would all have lunch together.”[4] At these gatherings and informal discussions in his mother tongue, Picasso experienced both the individual challenge of being uprooted and the collective experience of migration. He even went so far as to choose a Spaniard, Eugenio Arias, as his hairdresser. This anti-Franco veteran opened a barbershop in Vallauris. He continued to be close to Picasso and cut his hair from 1948 up until the artist’s death. Later on, Eugenio Arias gathered the drawings that Picasso had given him, as well as an engraving on his work case, at the Museo Picasso in Buitrago del Lozoya, near Madrid.

Summary

Summary