The ardent supporter of Picasso's work

Leiris, who had refused to be published during the Occupation, contributing only to clandestine and semi-clandestine magazines, became even more committed to Picasso after the Liberation. In October 1944 he signed the declaration of the Conseil national des écrivains (National Writers' Committee) defending Picasso, whose seventy-nine pieces shown at the Salon d'Automne had caused a scandal. The artist received a barrage of insulting letters: "I suspect that your soul may be as twisted and ludicrous as your scribbles." Or this other one, sent by a group of political sciences students: "All of those who recognize and value the mission of painting want to retch when they look at your repulsive paintings."[1] In fact, what really created an outrage was the announcement of the artist's support of the French Communist Party. On October 5, 1944, the report took up four columns on the front page of L'Humanité, illustrated with a photograph of the painter next to Marcel Cachin–editor-in-chief of the communist newspaper–Jacques Duclos, and Francis Jourdain, with a caption that has since been quoted many a time: "I came to the Party as one goes to the fountain."

Picasso's adherence had probably begun developing during the war when the artist met Laurent Casanova through the Leirises, who had kept him in hiding. Casanova, a direct collaborator of Maurice Thorez, one of the leaders of the communist resistance, was in charge of the Party's relations with intellectuals after the war. An article written by Leiris–who had no longer been a French Communist Party member for quite some time–about the "Free Picasso" exhibition at the Louis Carré gallery in June 1945 offers an ardent defense of a Picasso who was both valued and rejected. "His extraordinary capacity for renewal, due to which each of his recent series surprises even the closest followers of his art–a capacity that in Picasso's case reaches an unprecedented degree in the history of painting–could appear, at first glance, to be enough to explain this hostile reaction: in his constant metamorphosis, Picasso quickly gained a public that needed not just years, but centuries to be capable of fully comprehending and appreciating each one of his new 'manners'."[2]

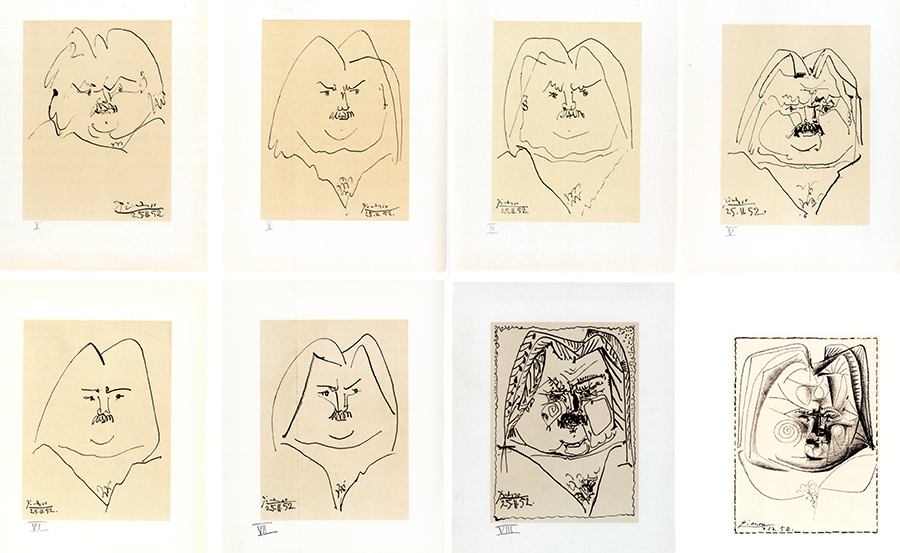

In 1948, at the Louise Leiris gallery, Kahnweiler organized his first exhibition in a long time, and published Les Sculptures de Picasso (Picasso's Sculptures) at Éditions du Chêne, a book he had put together after his visits to Boisgeloup. He gradually became Picasso's almost exclusive dealer. Beginning in the 1950s, a succession of Picasso exhibitions were held at the gallery, often presented with essays by Michael Leiris: "Œuvres récentes de Picasso" (Recent Works by Picasso, May 19 -June 13, 1953), and, later on, "Picasso. Peintures 55-56" (Picasso. Paintings 55-56, March 26-April 1957) for the exhibition that opened the gallery's new venue at 47 rue de Monceau. Michel Leiris introduced the catalogues for the 1957 engraving exhibition with a text titled "balzacs en bas de casse et picassos sans majuscules" (balzacs in lower case and picassos with no capitals), for the Meninas show in 1959, the exhibition featuring drawings in 1960, the January 1964 show with paintings on the subject of the artist and his model, the one with drawings in February 1968 ("Dessins 1966-1967", where Leiris found "these figures that you almost always assume are portraits, [even though] they are often none other than themselves...") and, finally, the May 1984 show (51 paintings, 1904-1972).

Summary

Summary