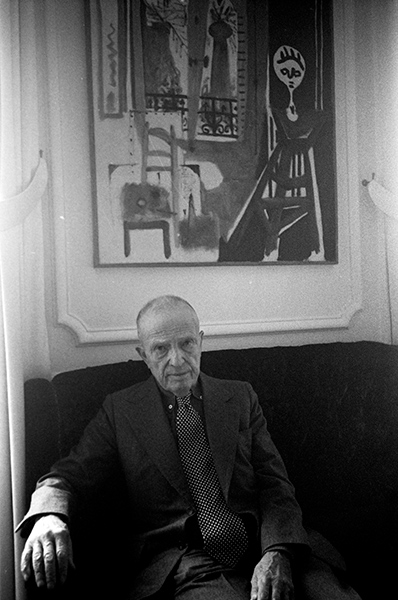

Catching Picasso in the act of painting

What was Leiris developing as he closely followed the artist? Generally disregarding questions of aesthetics and technique, over the course of fifty years Leiris sought an experience, a view of life that echoed his own concerns. When Leiris speaks of the artist's work, time and time again, "the relentless trailblazer by the name of Picasso" gave him the opportunity to reexamine the creative process. Straight away, he highlights "the fundamentally realistic character of Picasso's work." "For him, the issue was by no means as much, I believe, to recreate reality with the sole purpose of recreating it, as the incomparably more important issue of expressing all its possibilities, all its imaginable ramifications, so as to pull it in a little closer, within the hand's reach. Instead of being a vague connection, a distant landscape of phenomena, reality is thus illuminated through all its pores, penetrated; for the first time ever, it really becomes a REALITY."[1]

Many years later, Leiris continued to defend his view: "Picasso will have spent his entire life trying out all sorts of ways to visually transcribe a reality or to make figures present. And he will have done so out of an urge to experiment and invent: the point is, instead of leaving a record, to see how you can leave a record, and in this sense you could say that, for him, the true subject of the work is always the work that is yet to be done."[2] In this respect, Leiris remained true to Kahnweiler's view: "You can see the contradictions that make Picasso 'the available man,' the one who is always free unto himself. Two days earlier, he had hollered at me violently for passing judgment on 'abstract art.' Moreover, I am convinced that at those moments he would let himself be swept away by his need to contradict and that the praise of realism unveils his true tendency."[3]

But above and beyond these theoretical debates, as Isabelle Monod-Fontaine pointed out, Leiris's writings accompany both Picasso's work and his life: "It is no longer in the external, historical aspects that Picasso can be captured, but rather in the act of painting itself."[4] Thus, in 1964, after having transcribed a "confession" by the artist in one of his notebooks, dated March 27, 1963, "painting is bigger than me, I do what it tells me to do," Leiris wrote: "Clearly today Picasso does 'what he wants to do' with art, to which, at another level, it has been "bigger than him" to devote himself. But isn't it as though painting, having become his life, were telling him what to do more than ever before?"[5]

It was about Picasso that he dreamed in a delirious state after a suicide attempt, "an act that was the most diametrically opposed to the example that Picasso never ceased to give, because destroying myself meant radically depriving myself of a certain number of years that I could still have fully devoted to creative work."[6 Leiris even continued to pursue his close relationship with Picasso upon the artist's death, in a text titled "April 8, 1973"[7] "The dog and I had just walked into the courtyard behind the house when I saw my wife standing in one of the doorways. Before we had crossed the large cobblestoned space, she uttered those three words: "Pablo is dead." [...] And, staggering, I realized that (in addition to the loss of a friendship and of that always invigorating celebration, the discovery of his latest work, which time and time again bore witness to an extraordinary power of renewal) it was our own world–my wife's and mine, as well as that of many others, before then and from that moment on–that had just been dealt the blow of the puntilla."

[1] "Toiles récentes," 1930, Écrits sur l’art, p. 305

[2] "The Painter and his Model," originally in Roland Penrose and John Golding, Picasso 1881-1973, London, 1973, Écrits sur l’art, p. 363

[3] D.H. Kahnweiler, January 14, 1955, Quadrum, Brussels, November 1956

[4] Catalogue of the Louise et Michel Leiris donation, Centre Pompidou, 1984, p. 175

[5] "La peinture est plus forte que moi..." (Painting is bigger than me), Introduction to the 1964 exhibition catalogue, Écrits sur l’art, p. 345

[6] Fibrilles, La Règle du Jeu III, Gallimard, 1966, p. 110

[7] Frêle bruit, La Règle du Jeu IV, Gallimard, 1976

Summary

Summary