Under the shadow of blue: the preparatory drawings for La Vie

Picasso developed his initial idea for La Vie in several preliminary sketches, of which four are known, although, as we have seen, many are the works directly related to its genesis. The huge collection of drawings formally linked to the painting, coupled with its complex physical structure prove that the work was conceived and executed over quite a long stretch of time – several months – and that the compositional elements had not been completely defined when the work began.[1]

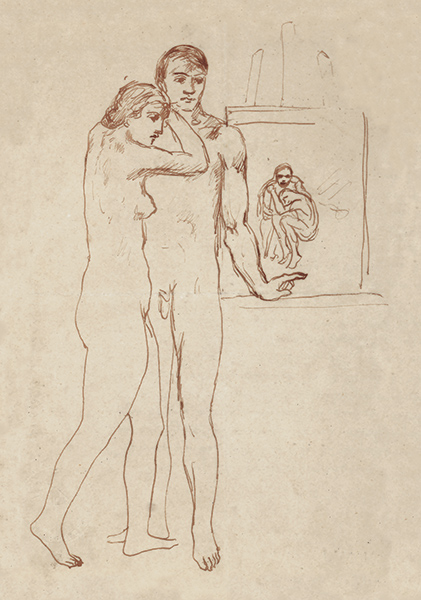

In this last series of drawings Picasso appeared as the protagonist, depicting himself nude in what was an audacious version of the traditional self-portrait as an artist (replacing the symbolic palette with an easel that holds a painted canvas). None of these drawings match the end painting, but which one of them bears a greater resemblance to the underlying image revealed in the X-ray?

No doubt the one that comes the closest is the one dated 2 May 1903 (fig. 18, p. 58). Made in sepia ink on the back of an invitation to the Ateneu Barcelonès, in our opinion it is too precise a drawing to be considered a mere sketch and yet it is also too small to be a model, and Picasso never needed models to scale to convey his drawings to canvas. So which is it, a confirmation of the process or a preliminary sketch?[2] In the event of it being a symbolic drawing of his work, the artist would be documenting a specific moment in the execution of his work, the support in itself would be irrelevant and, bearing in mind the technique (ink) it is reasonable to believe that it had been made in the studio or at least on a table. The outline of the male figure is a precise copy of the end work, save for the figure’s head and the cloth covering it, which was added at a later date.

In Study for La Vie (cat. 16, p. 96), another pen and ink drawing on paper, the couple appear fused in one block; while the position of the female figure resembles the one in the final painting, the male figure adopts a protective attitude. The woman is obviously pregnant[3] and appears much larger in the drawing, in a violent chiaroscuro devoid of spatial references.

Unlike the drawing kept in the Musée Picasso in Paris (fig. 1, p. 65), where the couple take centre stage, the composition in the homonymous Study for La Vie (cat. 18, p. 100) is structured in three vertical strips: from left to right: the couple forming a single block, the easel bearing a single painting and a male character in the third strip, all similar in size. An arch to the right of the image and what could be a lintel to the left are some of the references defining the space. Horizontality is emphasised by the ceiling beams and confirmed by the edges of the easel and painting.

The also homonymous Study for La Vie (cat. 19, p. 101) is another similar work as regards both format and technique. The composition here is also arranged in three vertical strips, with vanishing lines that meet in the middle of the picture, over the easel and the mysterious character’s hand. From left to right: in the first strip we find the block formed by the couple; the easel with its single work remains at the centre, as the male figure remains in the third strip. The perspective is achieved through the edges of the work and the easel in the background. The forms of the female figure match those of the final painting, particularly the left shoulder and the back in profile. The left arm of the male character splits into two, one points at the floor and the other one rises towards the character’s hand, as in other drawings.

The vertical lines have disappeared from the definitive picture of La Vie, and the arch has been moved to the left; the four characters float in space and form a sort of bas-relief where painting and sculpture coexist. Unlike Last Moments (a horizontal work, both as regards format and composition), La Vie was conceived in three vertical spaces, two of which are defined by the figures and the third by the paintings in the background. Picasso rotated the canvas (90 degrees), and became engrossed in an intense painstaking composition. The use of a range of almost pure colour completely erased the marks of the old painting, showing the colour underlying the different layers applied.

While we cannot establish the exact moment at which Casagemas appeared in La Vie, his presence was not fortuitous in the closing stages of such an intense creative period. The lack of a physical model symbolically brought the circle of memory to a close. The evocations first appeared three years before in the painting Le Bock (The Poet Sabartés) now kept in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, where Sabartés, who had arrived in Paris in autumn 1901, was depicted from memory on yet another recycled canvas[4] that became one of Picasso’s first blue portraits. In the meantime, the memory of the brutal reality of Saint-Lazare and its surroundings reappeared in Barcelona, in the new setting of Santa Creu i Sant Pau Hospital where he painted The Dead Woman (MPB 112.109).[5]

Although Picasso returned to Barcelona early in 1902, he did not sever his ties with Paris and took part in a group show at the gallery recently opened by Berthe Weill. The review published on the exhibition catalogue described his work as ‘brilliant’ and ‘solid’. A few months later, another critique of the show defined his painting as having a ‘stained-glass window effect.’ It mentioned as well the missing bursts of colour.

[1] See Francisco Calvo Serraller and Carmen Giménez (eds.), op. cit., p. 83.

[2] It could in fact be a similar document to the one in The Blind Man’s Meal.

[3] The X-ray image shows that marks of fresh paint were removed from the area of the abdomen (see p. 36).

[4] Anatoli Podoksik, Picasso. The Artist’s Works in Soviet Museums. New York / Saint Petersburg, Harry N. Abrams / Aurora, 1989, p. 149.

[5] ‘I once went to pick your father [Jacint Raventós i Bordoy] up at the hospital and he beckoned me into the “den”, where the dead bodies were kept. I saw a dead woman there who had suffered a gynaecological operation. Her face made a great impression on me, and when I went home I painted her from memory.’ Jacint Raventós i Conti, Picasso i els Raventós. Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1973, p. 24. Our translation from the Spanish.

Summary

Summary