From Barcelona Rooftops, datation

So there is not much margin for us to chronologically place Barcelona Rooftops: he either brought the work with him from Paris or else he painted it at some point during the nine months he remained in the Catalan capital. The underlying image was probably conceived during the latter, shortly before the shadow of blue pervaded his work: ‘The Blue Period truly began in Barcelona.’[1]

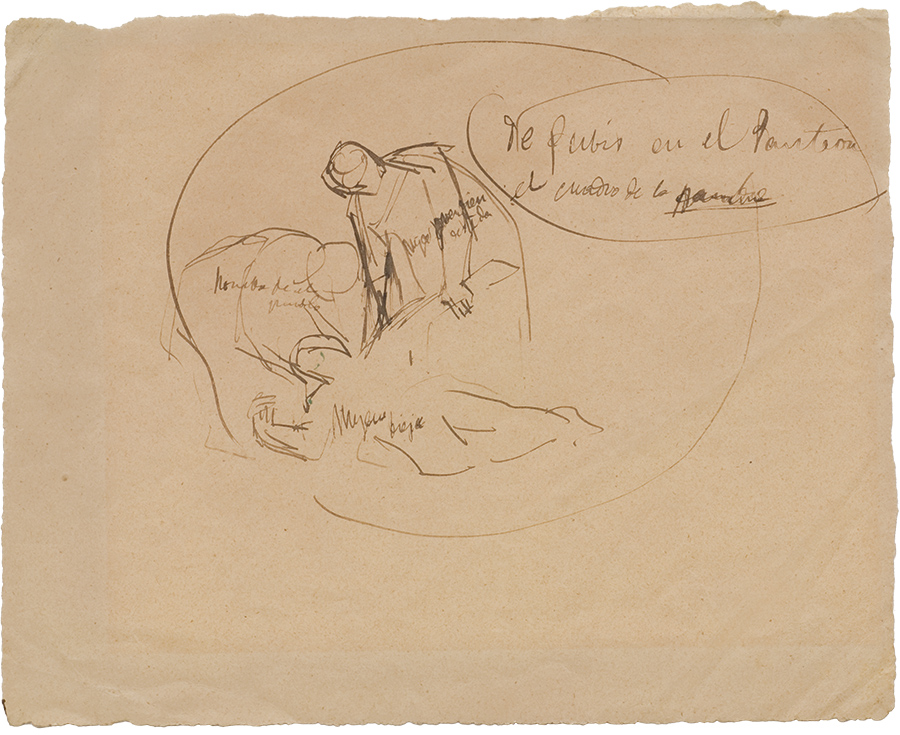

On 19 October 1902, Picasso returned to Paris, where at first he had no studio of his own. After settling in Montparnasse and then moving to the Hôtel du Maroc, he ended up sharing accommodation with Max Jacob. At this point his interest shifted from the merry street scenes of his earlier works to his new museum experiences, a change in setting that was accompanied by a new working atmosphere and repertoire of types that eased his transition to the style that evoked Greek art, characterised by more corporeal and comprehensible forms such as classicist figures dressed in long tunics. No doubt his visit to the Panthéon and the possibility of seeing the murals by Puvis de Chavannes proved so fascinating that he recorded both in several sketches dated early in 1903 (fig. 19, p. 60), shortly before he left Paris again.

Back in Barcelona, he painted The Blind Man’s Meal in late summer or early autumn of 1903,[2] one of the works that best sums up the spirit of the Blue Period. Following the same procedure as in Barcelona Rooftops, Picasso removed the excess fresh paint of the first work (a woman resembling the one portrayed in Seated Old Woman and the sketches for the decoration of a fireplace, dated June 1903) [3] in order to continue painting a different composition on the same canvas. At some stage of the process he concealed a feature (a head of a dog depicted in the lower area), leaving no other visible trace than a mention in a letter sent to Max Jacob.[4] He used Prussian blue in abundance, combined in some instances with white to emphasise its coolness, and on other occasions with warm colours such as ochres and yellows delicately applied in thin layers. Yet this old woman he had neglected, hidden under a layer of blue paint, did not disappear. Huddled up, geometrically squeezed into the almost square format of The Blind Man’s Meal, she is visually echoed in the woman portrayed in the lower sketched image in La Vie. In turn, this woman veils another composition in which a female figure welcomes a winged character, a work that was presumably executed in bright colours[5] and silhouetted in pure blue.

As mentioned previously, Picasso produced a group of similar works between mid-January 1903 and April 1904, both as regards colour and technique. Such formal similarities have been uncovered thanks to today’s image technology, which has enabled us to establish documentary connections with other contemporary works,[6] and strengthens our theory that La Vie cannot be understood as an isolated work but as forming part of a sequence comprising other paintings begun and abandoned, being replaced either immediately or a few years later.[7]

The couple we make out beneath Barcelona Rooftops is one of them. The range of colour we have identified matches that of his palette in 1900 and 1901, although its formal analogies reveal such a direct connection with La Vie that it must be considered a part of this ensemble. The scientific data we have presented concerning the work underlying Barcelona Rooftops consequently emphasises the fact that the genesis and making of La Vie covered a much longer period than was originally established.

ILLUSTRATIONS

p. 29

Ill. 1 Sebastià Junyent, Picasso the Painter, 1904

p. 32

Ills. 2 and 3 Blue Portrait of Jaume Sabartés, Paris, 1901 (full view and detail)

p. 33

Ill. 4 Female nude, Barcelona or Paris, 1902–03

Ill. 5 Woman with Lock of Hair, Barcelona, 1903 (verso detail)

p. 35

Ill. 6 Barcelona Rooftops (back view)

p. 36 and 37

Cat. 1 X-ray image of Barcelona Rooftops

Cat. 2 Infrared reflectography of Barcelona Rooftops

p. 41

Ill. 7 Self-Portrait with Raised Arm, Paris, 1902–03

Ill. 8 Study of Nude and Text, Barcelona or Paris, January 1903

p. 42

Ills. 9 and 10 The Blue Glass, Barcelona, 1902–03 (painting and X-ray image)

p. 43

Ill. 11 Ricardo Bellver y Ramón, The Fallen Angel, Rome, 1877

p. 44

Ill. 12 The Frugal Repast, Paris, 1904

p. 46

Ill. 13 Self-Portrait, Barcelona, 1900

Ill. 14 Self-Portrait, Paris, 1901

p. 48

Ill. 15 Infrared reflectography study of Barcelona Rooftops

p. 50

Ills. 16 and 17 The Dwarf, Paris, 1901 (full view and detail)

p. 58

Ill. 18 Study for La Vie, Barcelona, 2 May 1903

p. 60

Ill. 19 Sketch of Saint Geneviève Supplying Paris, by Puvis de Chavannes, Paris, January 1903

[1] John Richardson; Marilyn McCully (col.), A Life of Picasso, vol. 1: 1886–1906. New York, Random House, 1991, p. 327.

[2] Oil on canvas, 93.5 × 94.6 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

[3] MPB 110.015, mpb 110.494, MPB 110.505 and MPB 110.517.

[4] Letter from Picasso to Max Jacob, 6 August 1903. The Barnes Foundation, Merion, Pennsylvania (BF714).

[5] The analyses carried out to date on La Vie have established only the layers of the two main compositions at three points along the edge of the painting, although the colour underneath can be appreciated in several parts of the work.

[6] One of the pictures studied in depth, for instance, is The Old Guitarist kept in the Art Institute of Chicago, where the internal layers of paint have revealed two hidden, and very different, compositions: the figure of an old lady and another work showing a female character resembling the type in Seated Old Woman (MPB 110.015) and Female Nude (cat. no. 9, p. 85), respectively. Curiously enough, instead of painting on a commercial canvas this time Picasso used a thin sheet of wood recycled from an old piece of furniture.

[7] Such as La Coiffure, for instance (Paris, 1906), which he made by rotating the canvas 180 degrees and covering previous paintings up. Apparently he reused the canvas three times. The innermost layer of paint, i.e. the first, depicting a standing figure that occupies most of the canvas, could have corresponded to a work produced in Barcelona in 1902. Instead of attempting to conceal this layer, Picasso took advantage of the blue background, which he veiled with a layer of earthy hues.

Summary

Summary