For Picasso, an adventure of transmission

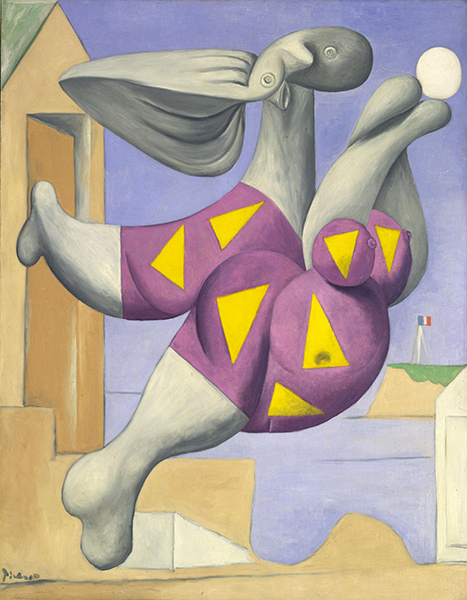

Kootz continued to have an ongoing relationship with Picasso, writing to him and visiting him regularly in southern France until he closed down his gallery for good in 1965. Although he continued to purchase the occasional work, Kahnweiler was no longer willing to let him have many. Kootz's last exhibition of Picasso ran from September 30 to October 18, 1958, and once again, after only having managed to buy four paintings, he made the most of this small number of pieces, titling his show "Picasso Five Master Works." Three of these paintings are now in the Museum of Modern Art collection in New York: Paloma Asleep, 1952 [Z. XV, 233], sold before the opening to Mrs. Louise Smith, Seated Nude, 1940 [Z. X, 302], reserved by Kootz for his personal collection, and Bather with Beach Ball, 1932 [Z. VIII, 147], purchased by Victor Ganz. The group was completed with Woman in an Armchair, listed in the catalogue as belonging to the David M. Solinger collection, possibly already sold or loaned in New York, and Portrait of Hélène Parmelin, 1952 [Z. XV, 214] which Kootz also wished to keep for himself.

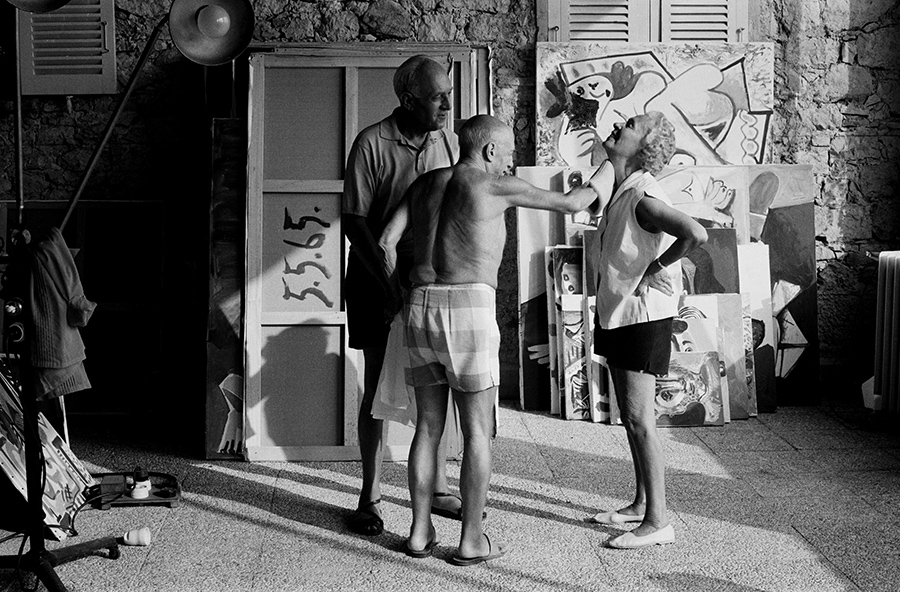

Kootz first mentioned to Picasso that he was tired and was thinking of closing down his gallery in 1963, but did not take his leave until 1965. In a poster from October 1965 announcing "Picasso, 14 Paintings" at the Kootz Gallery, exhibition that we have not been able to trace, we read that the paintings show "Picasso's ongoing generosity, which allowed Sam Kootz to make his personal choices since 1946." Picasso had an active role in the New York gallery's success, and remained in contact with the dealer until 1965. Looking at the photograph taken by Lucien Clergue in 1965 showing Jane and Sam Kootz in Picasso's studio at Notre Dame de Vie [ill. PH 469], we can hardly doubt that the two men ended up having a sincere friendship and mutual respect. And Kootz never concealed the fact that he owed everything to Picasso, as he recalled in an interview from 1964: "Quite frankly, we could not have existed unless I had had Picasso shows. Picasso paid continuously for the period of the first ten years of the gallery’s existence. If we had to exist on the sales of our American men, we would have absolutely been dead at the end of those ten years. But the sales of Picasso, who was enormously impressed when I first saw him when I showed him photographs of all my American men and told him frankly that I was subsidizing these men and that I wanted his pictures as a means of helping me to run the gallery the same Cezanne paid for his upbringing by Paris Galleries, which appealed to him enormously. And he gave me the pictures to sell."[i]

[i] Dorothy Seckler, op. cit.

Summary

Summary