Historians have often taken the end of Picasso’s collaboration with Diaghilev to coincide with the beginning of his estrangement from Olga, and accordingly his painting The Three Dancers has long been regarded as the last great work the artist devoted to the theme of the ballet.45 With this work, completed in May 1925 after his return from Monte-Carlo,46 the painter inaugurated a new style that André Breton claimed for Surrealism, publishing an illustration of the picture in his review.47 Although the biographical association of The Three Dancers with the death of Ramon Pichot is well attested today,48 a parallel interpretation would tend to reconcile various theses about Olga’s presence among the three figures in this round dance: sometimes perceived as the writhing maenad on the left,49 sometimes as the flat, asexual geometric figure in the center,50 whose Christ-like pose recalls a gesture of Lopokova’s in the printed photo of 1916. Yet Olga might also be the figure on the right, whose “phantom reality”51 evokes the ethereal character of the imaginary Sylphs, elemental spirits of the air in alchemy and Romantic mythology. The bare legs of the central figure and the figure on the right reveal the “phallic” identity of the female dancer, an object of fantasy represented from this date onward without her pointe shoes, an exclusively feminine attribute.52 In this Dionysiac representation of the Three Graces, “Olga the ballerina” would ultimately become a mere dancer progressively stripped of her femininity and gradually obliterated in a syncopated, rotating rhythm captured in three shots like a chronophotographic image by Étienne-Jules Marey.53

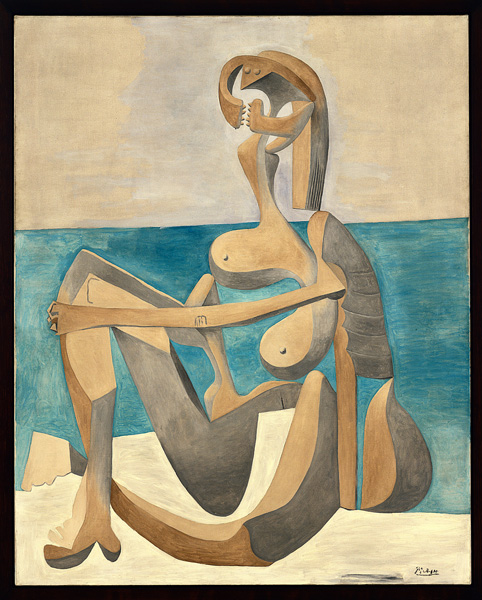

The icon of the ballerina flirts as well with that of the bather, from the bacchanales of La Mimoseraie in Biarritz (1918)54 and the illustrations for the May 1921 Ballets Russes program at the Gaité Lyrique, to the bathers at Dinard (1929) and certain sculptures from the artist’s workshop at Boisgeloup (1931).55 Long associated with Marie-Thérèse Walter, the painter’s mistress after 1927, certain of the Dinard bathers have recently been related more closely to the figure of the ballerina.56 Olga’s practice of her dance exercises during their summer vacations, often while wearing her bathing suit, encouraged the union of both themes and provided Picasso with a new pretext for dialogue with the painters of the nineteenth century, from Puvis de Chavannes to Cézanne. The Nude Standing by the Sea, for example, appears in the fifth position of classical ballet, presenting the subject to the painter’s eyes with the same composure as the dancer facing the camera lens in 1916. The stiffness of the model’s pose, accented by the palette of mineral colors characteristic of the Norman coast, borders on the extreme in the baleful version of the Large Bather:57 the shadow that hovers about the wasted figure of the model, painted without compassion, seems an omen of the end of the dancer’s reign.

On 22 January 1932 Picasso again placed Olga at the heart of his painting in a masterpiece that he entitled Repose (Le Repos): here the ballerina, the embodiment of femininity and grace, is metamorphosed into a creature both suffering and menacing, balanced on an armchair, arms arched over her head. The supernatural aspect of the Sylphide has definitively overridden her Romantic dimension and the aggressive colors have prevailed over the purity of the “neoclassical” line. The couple separated in the summer of 1935 and the ballerina, the painter’s muse and subject of study since 1917, would be relegated to the wings, reappearing only very rarely thereafter in the master’s work.58

Cécile Godefroy

Art Historian, Researcher at the Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte (FABA)

This is the first study based on the archives of the Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte (FABA). It was commissioned by the foundation in connection with the Picasso Looks at Degas exhibition and explores the preeminent theme of the dancer in the work of Degas, as well as Picasso’s interest and involvement in the ballet and his images of Olga Khokhlova as a dancer. In the course of the work done for this study, FABA undertook the process of cataloguing its photographic holdings that concern Olga Khokhlova, as well as her entire personal correspondence.

FABA and the author warmly thank Elizabeth Cowling and Richard Kendall, curators of the exhibition “Picasso Looks at Degas” and editors of the catalogue, as well as Anne Baldassari, Evelyne Cohen, Sylvie Fresnault, and Jeanne-Yvette Sudour of the Musée national Picasso, and Isabelle Gaëtan of the Musée d’Orsay for their kind assistance in the preparation of this text.

45. Cooper, Picasso Theatre, op. cit., p. 49.

46. In the spring of 1925, while in Monte-Carlo with Olga and Paulo to attend the Ballets Russes performances, Picasso executed a series of life studies of dancers exercising at the bar or at rest (see Z.V.427--38; Z.V.447--50; Z.V.452--55).

47. La Révolution Surréaliste, n°4 (July 1925), p. 17.

48. See, for example, Ronald Alley, Picasso : The Three Dancers, London: Tate Gallery, 1996.

49. Elisabeth Cowling, Picasso. Style and Meanings, London: Phaidon, 2002, pp. 463--69.

50. Richardson, A Life of Picasso…, op. cit., pp. 282--83.

51. Françoise Levaillant, « La Danse de Picasso et le surréalisme en 1925 », in L’Information de l’histoire de l’art, 11, n°5 (November-December 1966), pp. 205--14 [213]: “la réalité fantomale.”

52. For two discussions of gender and the symbolism of pointe shoes, see L. Garafola, « Reconfiguring the Sexes », in The Ballets Russes and Its World, op. cit., pp. 254--68; and Susan Leigh Foster, « The Ballerina’s Phallic Pointe », in Corporealities : Dancing Knowledge, Culture and Power (S. L. Foster ed.), 1996. Repr. London: Routledge, 2005, pp. 1--24.

53. According to Anne Baldassari, this “cinétisme” can also be seen in the drawing The Three Dancers, 1919--20 (Musée national Picasso, Paris, MP 840; Z.XXIX.432). See « La lumière et le trait », in Le Miroir noir, op. cit., p. 173.

54. Z.III.221--230.

55. See Richard Kendall, « The Ballet : Work, Pleasure and Vice », in Picasso Looks at Degas, exh. cat. (Elizabeth Cowling and Richard Kendall éds.), Williamstown, Mass.: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute ; Barcelona: Museu Picasso, 2010, pp. 104--55 [150--51]. Cécile Godefroy, « Baigneuse », in Pablo Picasso : 43 Works (Cécile Godefroy and Marilyn McCully éds.), Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte (FABA) ; Museo Picasso Málaga, pp. 122--9.

56. Richardson, A Life of Picasso, op. cit., p. 334.

57. Dated 26 May 1929 (Musée national Picasso, Paris, MP 115; Z.VII.262).

58. The couple remained officially married for the next twenty years. Olga died in Cannes on 11 February 1955.

Summary

Summary