Desnos, A Poet in the Resistance

Robert Desnos met Picasso during the Dada and Surrealist periods, most likely in November 1925, when the Peinture Surréaliste group show was held at Galerie Pierre. Desnos, the only participating poet, included his drawings. Robert Desnos experimented with the many aspects of Surrealist modes of expression. According to Michel Leiris, "Robert Desnos was capable of speaking Surrealist, applying to spoken language the same submission to an almost automatic system which other followers enjoyed applying to their written discourse." With an inquisitive mind and a love for modern means of communication, which he eagerly adopted in order to develop his talent for improvisation, Desnos was a pioneer in the use of radio, exploring its multiple possibilities after his dramatic break with André Breton in the late 1920s.

Robert Desnos' interest in Spain and his opposition to Franco brought the two artists closer. "Oh what is happening in Spain/Why is it that I'm here and tired/What the hell am I doing here?" he wrote in one of his notebooks.[1] However, it was during the Occupation that their relationship became a steady friendship. Desnos and his wife Youki frequented the group of artists who met at Le Catalan, the restaurant on Rue des Grands-Augustins opposite Picasso's studio, and at Les Deux-Magots, in Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

Demobilized in 1940 and firmly determined to fight against Nazism, Desnos joined the editorial staff of Aujourd'hui, the newspaper recently founded and directed by his friend Henri Jeanson. After Jeanson was dismissed, Desnos decided to stay on and became the music critic for the daily, which had fallen under the control of the occupying forces. In 1942, he reinforced his commitment to the Resistance and became Agent P2 in the Agir network, publishing his poems clandestinely under several pseudonyms (Lucien Gallois, Valentin Gallois, Pierre Andier, and Cancale).[2] At times he was barely able to conceal his opinions, going so far as to publicly slap a journalist from Je suis partout in the face.

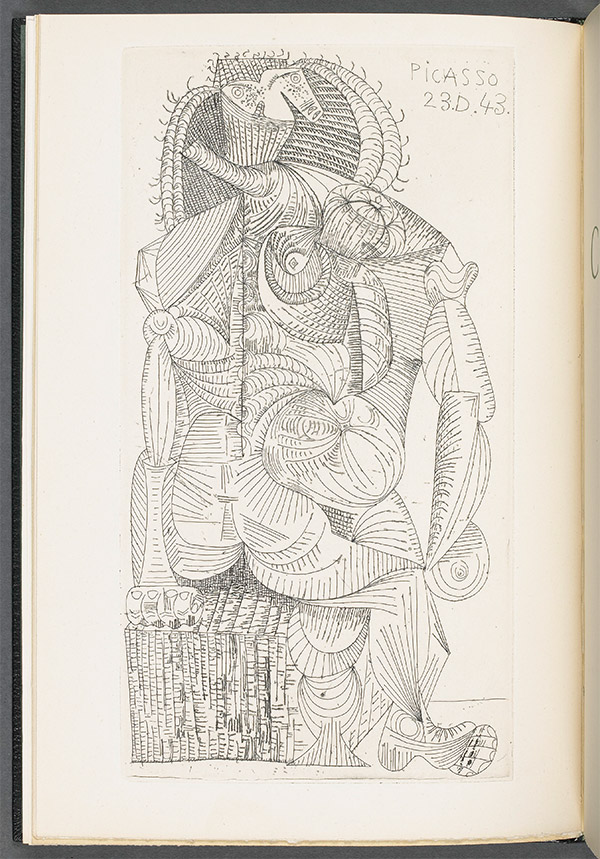

At the end of 1943, Picasso produced an etching to illustrate the poet's collection Contrée, which was published in 1944 by Robert J. Godet, who had already published État de veille in 1943. Desnos also published with Éditions de Minuit, founded by Pierre de Lescure and Yvonne Desvignes, whose production Ernest Aulard printed clandestinely. Desnos and Picasso lived in the same neighborhood and saw each other often; Desnos began to write about the artist, whom he admired and described in terms of "the marvelous world that he never ceases to shape with his hands" in which "he moves with ease" with "a need for freedom that could not be mistaken."[3] Picasso, who knew about his friend's political views but was unaware of the extent of his involvement in the Resistance, urged him to leave the staff of Aujourd’hui, an openly collaborationist newspaper.

On February 19, 1944, Desnos went to visit Picasso at his studio for the last time; he was arrested by the Gestapo three days later. The painter was deeply affected by the news of his arrest. From the Compiègne train station, Robert Desnos was deported to Auschwitz and from there to Buchenwald, Flossenburg, and Floha. He was on the convoys of deportees, forced to walk for miles on end until they collapsed in exhaustion and, in many cases, died, while the SS fled the advance of the Russian troops and the Allied bombing raids. He arrived at Terezin, near Prague, on March 7, 1945. Severely weakened, he died on June 8, 1945, only a few days after the camp was liberated.

[1] Les Sources de la nuit, notebook no. 4, July 24, 1936.

[2] Pierre Seghers, La Résistance et ses poètes, Éditions Seghers, reprinted in 2022, pp. 212-213.

[3] Robert Desnos, quotes from the introduction to Seize Peintures (1939-1943), quoted by Peter Read in Cahier Pablo Picasso, Éditions L’Herne, 2014, p. 288.

Summary

Summary