Like Delacroix, the freedom to paint

We know how acutely aware the artist was of the world events around him. Deeply marked by the wars and conflicts he had witnessed, Picasso read the press and listened to the radio, which was in the process of expanding, offering a new tone, popular broadcasts, and a focus on information, while giving priority to reports from the field (the number of receivers in France had risen from 5.3 million in 1945 to 10 million in 1958, becoming a major medium of communication). Picasso reflected, pondered, and cast a personal, watchful eye on world affairs, conveying both their violence and their harmony with lyricism and poetry. He depicted modern life, laying bare all its joy, its beauty, and its suffering.

"I paint against the canvases that are important to me, but also in accord with what's missing in them."[1]

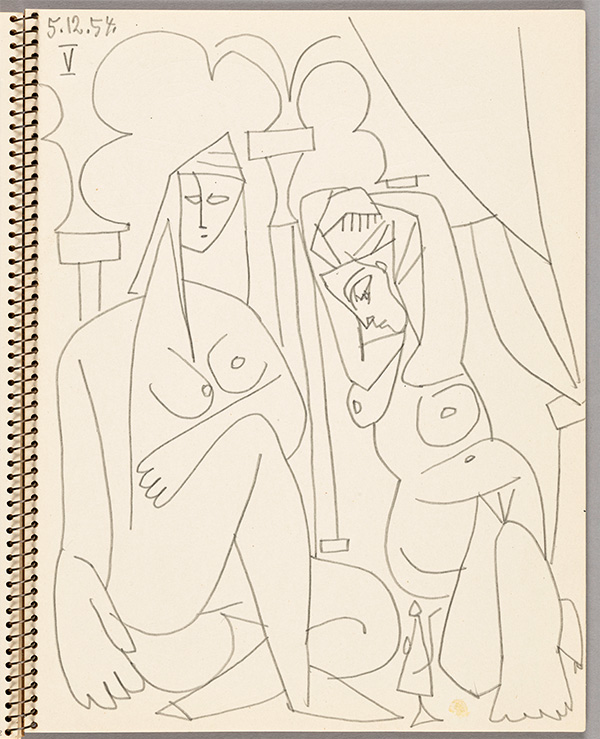

Femmes d’Alger turned out to be the catalyst for a series completed between November 1954 and February 1955. Picasso admired Delacroix, particularly for having managed to claim a certain freedom in his painting and reject the tedious academic rigidity that prevailed at the time. In the course of their respective lives, through the endless search for new modes of expression, showing a strong commitment, they shared a certain irreverence towards tradition, which they both respected nonetheless. Picasso was likely to have identified with his elder's rebellious temperament. "In Picasso's view, Delacroix deserved credit for having upended academic immobility and created a world in which painting was the sole organizing principle."[2] Each in his own way, they renewed and transformed painting, pondered the lessons of their masters, and translated the language of the past to shape it in their own image, fascinated by gesture and talent. Like Delacroix, Picasso "updated, explained, stripped down, radicalized."[3] Picasso's variations, from A to O, consisted of six small paintings and seven large compositions. According to art historians, his motivations for undertaking this project were many: "they range from an incidental resemblance between his new partner Jacqueline and the woman sitting sideways with the hookah, to the myth of a sensuous, voluptuous Orientalism; to historical connections, such as Matisse's recent death in November 1954 —thus a tribute to color— and to the beginning of the Algerian insurrection."[4]

[1] Quote from Picasso by André Malraux in La Tête d’obsidienne, Paris, Éditions Gallimard, 1974, p. 124.

[2] Pierre Daix, Dictionnaire Picasso, Paris, Éditions Robert Laffont, 1995, p. 244.

[3] Philippe Dagen, "Les œuvres des grands maîtres passées au scalpel pictural de Picasso," Le Monde, October 8, 2008.

[4] Marie-Laure Bernadac, "Variation Delacroix," Picasso et les maîtres, exhibition catalog; Paris, Éditions RMN, 2008, p. 204.

Summary

Summary