Breton, Picasso, and the Centennial of Surrealism

One hundred years after the publication of André Breton's manifesto,[1] the Musée national d’Art moderne has retraced the extraordinary journey of surrealism, a movement that unquestionably had a lasting impact on the history of ideas and art, and of which Picasso, close to André Breton, was a privileged witness.

In his sensitive quest to understand the world and build "another life", André Breton used poetry, writing, and painting to exchange and confront his views with many intellectuals and artists. His connection with Picasso was by turns distant and intimate. Their relationship was much like "a love affair, with its thrills, its declarations, its highs and lows, its enchantments and disenchantments, its rifts and reconciliations."[2]

Picasso met André Breton through Apollinaire. However, Breton showed greater interest in Picasso from the 1920s onward, and seems to have become fully aware of his art in 1922, recognizing its importance for history in the making; in his lecture "Caractère de l’évolution moderne et de ce qui y participe" Breton wrote: "This is the first time that such a strong element of transgression has come to the fore in art, one that we shall not lose sight of as we move forward."[3]

The young poet truly venerated the painter, as shown in his letters from 1922 and 1923. "My admiration for you is such that at times it seems impossible to express."[4] Breton, who worked for the couturier and major collector Jacques Doucet, tried to convince him to purchase La Danse, which may be considered one of Picasso's most surrealist paintings, although its aesthetic interpretation varies depending on the eye of the beholder.[5] Breton reproduced this painting along with Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in La Révolution surréaliste —Number 4, dated July 15, 1925, his first issue as director of the journal — in which he published "Le surréalisme et la peinture", mentioning Picasso several times. However, the artist emphatically denied any surrealist influence on his work. According to Breton, the painter embodied "the essential —that is, the project for existence, the interaction between man and the world, between art and life, the ongoing tension between an awareness of political and social realities and the manifold riches of subjectivity."[6]

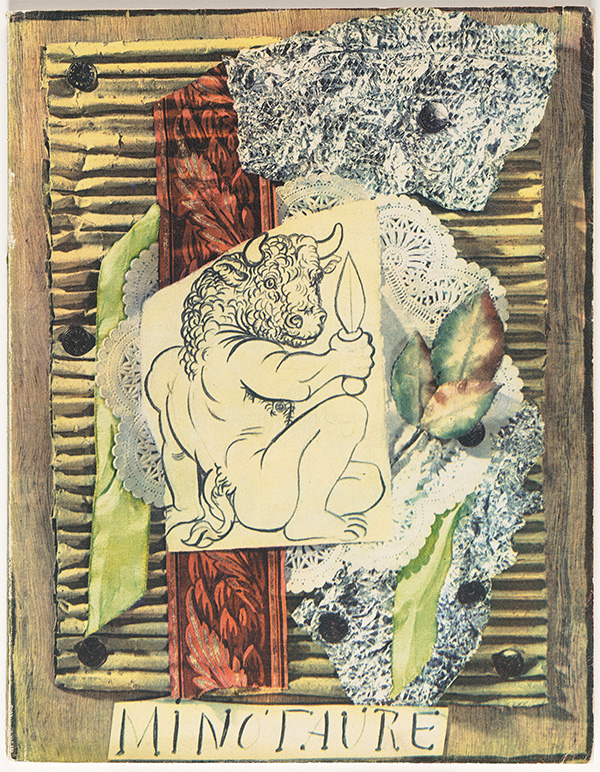

In 1933, Picasso —who nevertheless, by his own admission, was fairly close to the surrealists— completed an assemblage for the first issue of the journal Minotaure, published on June 1. In "Picasso dans son élement", illustrated with photographs taken by Brassaï in the artist's studio, Breton praised his work, concluding: "The boundaries assigned to expression have been crossed once again. […] Everything in the world that is subtle, all that which knowledge can only grasp with difficulty by degrees (the passage from the inanimate to the animate, from objective to subjective life, the three purported kingdoms) finds the most striking resolution here, achieves its most mysterious and sensitive unity."[7]

On September 25, 1935, André Breton wrote to Picasso: "I wish I could be there to shake your hand, and put into this gesture all the emotion I've always felt when thinking of you; you know how much I admire you and how much I dreamed, when I was young, of occupying a small place in your life."[8] This letter reveals a certain degree of intimacy between the two men, subtly woven over the years. It was undoubtedly the period when Breton was closest to the artist.

In 1936, Breton also published "Picasso poète" in Cahiers d’art, analyzing Picasso's work in that area. The article sought to decipher the artist's approach in his semi-automatic poems, exploring the relationship between words, images, and the poetic background of an artist for whom painting and poetry were one and the same.

Between January and July 1940, when Breton was posted to Poitiers as chief medical officer, Picasso and Dora Maar took in his wife Jacqueline and their daughter Aube in Royan, where Breton would visit them when he was on leave. Later on, Breton went into exile in the United States. The two men had a falling out when Breton returned after World War II; during his absence, Picasso had joined the Communist Party. Breton announced their final rift when they ran into each other on the street in Golfe Juan. In a text, "80 carats... mais une ombre", published in Combat d'Art in November 1961 on the occasion of Picasso's 80th birthday, Breton spoke out against Picasso's political choices, justifying their separation.

The relationship between the two men was by turns emotional, artistic, intellectual, and political. Under such conditions, it was difficult to keep up the connection that André Breton seemed to expect, especially as Picasso appears to have kept a certain distance from the surrealist movement. Breton may have asked and expected too much of Picasso.

Surréalisme, MNAM-Centre Georges Pompidou, from September 4 to January 13, 2025.

[1] André Breton, Manifeste du surréalisme, éditions du Sagittaire, 1924.

[2] Marie-Laure Bernadac, André Breton, la beauté convulsive, MNAM, Centre Pompidou, 1991, p. 210.

[3] Dictionnaire Picasso, p. 139.

[4] Letter dated October 9, 1923. Laurence Madeline, Les Archives de Picasso, RMN, 2003, p. 212.

[5] John Richardson, A Life of Picasso, Pimplico, 2009, p. 293.

[6] Marie-Laure Bernadac, André Breton, la beauté convulsive, MNAM, 1991, p 211.

[7] Minotaure, June 1, 1933.

[8] Les Archives de Picasso, p. 212.

Summary

Summary