Picasso: “We are what we keep. »

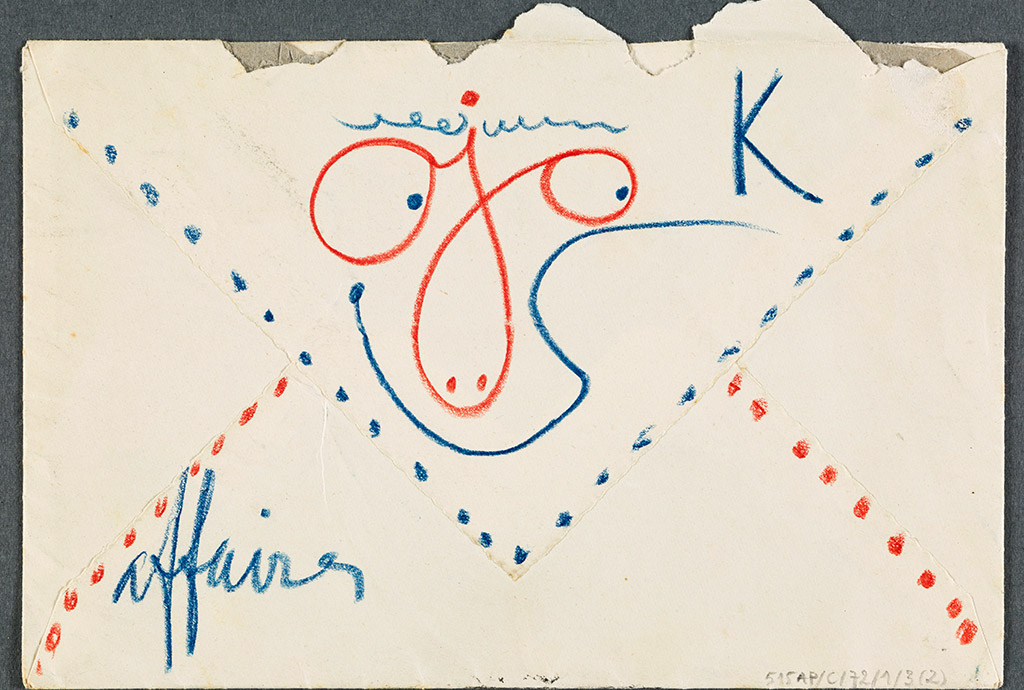

In principle, the heirs propose the works they give as payment of their estate taxes; however, in this case, they let the State make the choice. "By a tacit agreement with the heirs, and for the first time since the dation system existed, the State was the one to propose its selection to the heirs. […] Better still, the agreement stipulated that the State would make its choice from the entire estate before it was divided and dispersed. That was a crucial point; it allowed for a meaningful selection to be made, an essential condition for creating a museum."[1] With the help of those close to the artist, Dominique Bozo proceeded to take stock of everything that Picasso had kept with him, allowing for a better understanding of his work and his approach. "For those who had access to the things that Picasso protected or simply kept, [...] what was particularly striking was the scarcity or the virtual absence of unfinished or abandoned works, which one usually comes across in other studios. [...] Picasso had kept all his paintings and sculptures as an active backdrop for his daily life, as if they were found objects, provocative and necessary, placed there awaiting a look or a compliment."[2] As he explained in a television interview, "what certainly came as a surprise with the dation was to find pieces in the Picasso collection that we didn't even know existed and he had kept, pieces that led up to the creative surge of the Demoiselles d’Avignon and Cubism […] along with everything related to his family life, his private life."[3]

In the catalogue for the Grand Palais exhibition,[4] Dominique Bozo wrote about the painter's relationship with various institutions, but also about his tendency to keep everything within close range, accumulating without sorting, and holding on to everything in his studios, from the tiniest to the most elaborate of pieces, thus allowing for a fully cohesive body of work, representative of his tireless activity. Regarding the dation, he wrote: "So finally, in 1979, several years after Picasso's death, thanks to the potential of an exceptional law the likes of which will probably never be seen again, we have an entire museum set up by the painter himself: the museum Picasso had wished for."

A quote from Picasso himself is an apt description of the enormous trove discovered after his passing: "You are what you keep."

Whenever Picasso moved to a new studio, he left his furniture and paintings behind—at the Rue La Boétie, the Château de Veuvenargues or Notre-Dame-de-Vie—and no one ever touched them again. Upon his death, 1,885 paintings, 15,000 drawings, 1,228 sculptures, 3,222 ceramic pieces, and more than 30,000 prints were discovered. Some were paintings that the artist had bought back to fill the gaps left by the years of poverty when he had to sell everything in order to get by; a large part was almost or entirely unknown. It was a new Picasso mystery: a body of secret, forgotten work, particularly drawings. According to Michel Guy, "the overall interpretation of Picasso's output has to be reconsidered in view of the new discoveries." Dominique Bozo, as admiring as he was stunned by the "secret" collection, wrote about this intimate realm: "Picasso had kept all these paintings, these sculptures, to surround himself with them as his personal 'objects.' Here again, we see the evidence in the many photographs of his various residences; in them we can identify certain select pieces that reappear in each step along the way."[5]

Summary

Summary