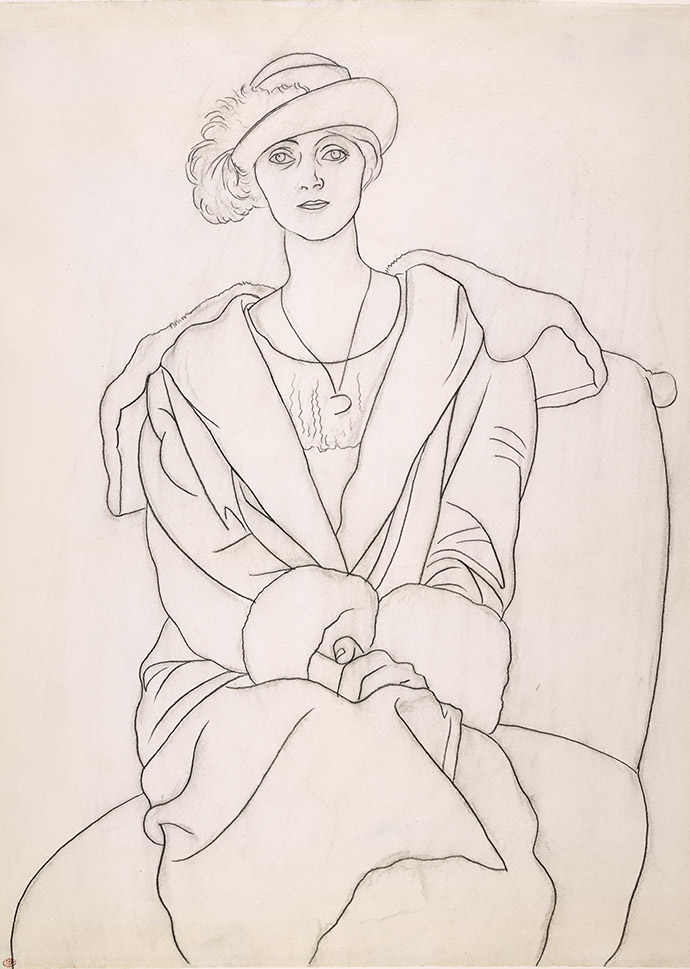

A dation as the precise evocation of the creative process of the artist.

The Musée national Picasso-Paris is one of the members of the commission, and therefore it is pertinent to recall the circumstances and decisions that allowed for the acquisition of a group of works that led to the birth of this museum. Given their quality, their scope, and the variety of art forms they cover, the holdings of the Musée national Picasso-Paris constitute the only public collection in the world that provides an overview of Picasso's entire production in painting, sculpture, printmaking, and drawing, while allowing for an accurate reconstruction of the artist's creative process. The collection was created thanks to a dation, a payment in kind for estate taxes to the French State made by the heirs of Pablo Picasso in 1979.

The purpose of Law No. 68-1251 of December 31, 1968, "aimed at promoting the conservation of the national artistic heritage," proposed by André Malraux, was to enable the implementation of new means for increasing museum and library collections, to ensure that works of high artistic or historical value remain in France, and to preserve the character of certain historic houses for the benefit of the visiting public. It is sometimes misleadingly referred to as the Dations Law, when in fact it was also intended to facilitate other arrangements such as donations. Article 2 of the law stipulates that "any heir, beneficiary, or legatee may pay estate tax by handing over works of art, books, collectibles, or documents of high artistic or historical value." The decree for its application was published almost two years later; it is Decree No. 70-1046 of November 10, 1970, which created a commission that "issues an opinion on the artistic or historical interest as well as on the value of the donated property." The commission was not actually established until October 1971.

Gathering a group of the artist's works for the national museums was no easy task, given Picasso's tense relationship with the French cultural administration. Nevertheless, according to the historian Pierre Schneider, Picasso had expressed his wish to make an important donation: "In 1966, when the major retrospective of Picasso's work was held at the Grand Palais, André Malraux did nothing to prevent his eviction from the studio on Rue des Grands-Augustins. The painter was furious, refused the Legion of Honor, snubbed the exhibition, and changed his mind about the considerable donation he was about to make."[1]

However, Picasso was known to be quite generous—both in Paris, where he had donated ten major pieces to the Musée national d’art moderne directed by Jean Cassou, and in other regions. The Musée de Grenoble, the only French museum to have purchased one of his works during the interwar period, received a gift from the artist thanks to the efforts of its curator Andry-Farcy (Femme lisant, 1920). After the war, following his stay in Antibes in 1946, Picasso donated 23 paintings and 44 drawings to the town, further enriching the collection in 1948 when he added 78 ceramics produced at the Madoura studio. In 1949 Picasso gave the sculpture L’Homme au mouton to the Town of Vallauris and installed it in an empty chapel: he then came up with the idea of creating a work, La Guerre et la Paix, whose 18 panels were completed in December 1952.

A dation offered a spectacular and unexpected opportunity to add the painter's works to the French national collections.

[1] Pierre Schneider, "Picasso", L’Express, September 29 - October 5, 1979, p. 140.

Summary

Summary