Picasso Poet, An Exhibition at the Musée national Picasso-Paris.

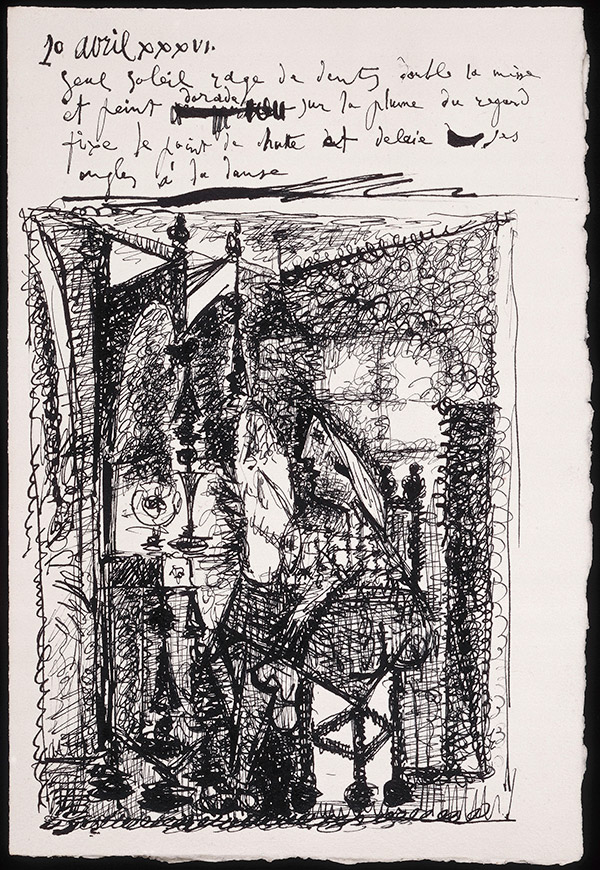

The Musée national Picasso-Paris presents an exhibition that reveals Picasso's writing in all its splendor. Small and compact or flowing sumptuously, the artist's hand reflects his mood of the moment. His mind wanders over the paper or feverishly jots down thoughts and ideas so as not to forget them. Picasso loves writing insofar as it forms a whole with other means of artistic expression. He explores its possibilities, crosses it out or circles it, erases or underlines it, and sometimes draws it. He disregards punctuation but pays attention to spaces and “blanks.” Picasso the writer pokes fun at the meaning of words but imbues them with emotions.

This is the ensemble shown at the Picasso Poet exhibition. The voice of Robin Renucci, deep and warm, and that of Picasso’s lifelong friend, the faithful Jaime Sabartés, accompany the visitor in the reading of poems—some of roughly 350 that the artist wrote from 1935 onwards in French and in his mother tongue. The artist is known to have had a strong interest in literature and writing from a very early age, long before he began to practice his word skills on a regular basis.

In notebooks, on loose sheets, on beautiful paper (sheets of Arches paper folded in half) or small scraps, he jotted down poems and stories, series and variations, poems with rhymes and stanzas. He wrote about the subjects closest to his heart, revealing his inner world, a mix of darkness and a love of life, of hope and despair. When he began to write this way, his personal circumstances were complicated: his relationship with his partner was in crisis, his secret lover Marie-Thérèse was about to give birth to a little girl, and it was rumored that he was thinking of giving up painting. His painting offers us certain clues for understanding his poetry, in which he voices his deepest feelings. In turn, his poetry expresses what his painting does not tell us.

Picasso focuses on typography as much as on the staging of words, the beauty of handwriting, calligraphy, and the visual layout of words and phrases, the shapes of imaginary letters. His writing follows both his intellectual and his personal development. He produced poem-drawings which eventually led to new paintings. The artist declared to Roland Penrose: “You can write a painting just as you can paint sensations in a poem.”[1] The exhibition is organized as a rich dialogue between painting and writing, an extension of Picasso's visual expression.

The exhibition also shows the painful years from 1937 onwards, when Picasso followed the disasters of the war in Spain from afar, and his new partner Dora Maar is depicted as an image of suffering in The Weeping Woman. Needless to say, the show evokes Picasso’s relationship with Surrealism, even though he justified resorting to automatic writing, claiming that in his case was by no means “calculated” but rather an innate expression of his talent.

Later, after the war, Picasso harmoniously combined poetry and lithography in his print work.

Picasso Poet, curated by Marie-Laure Bernadac and Androula Michael. Exhibition at the Museu Picasso de Barcelona from November 7, 2019 to February 23, 2020, and at the Musée national Picasso-Paris from July 21, 2020 to January 3, 2021.

[1] Quoted in Roland Penrose, Picasso, Paris, Flammarion, 1982.

Summary

Summary