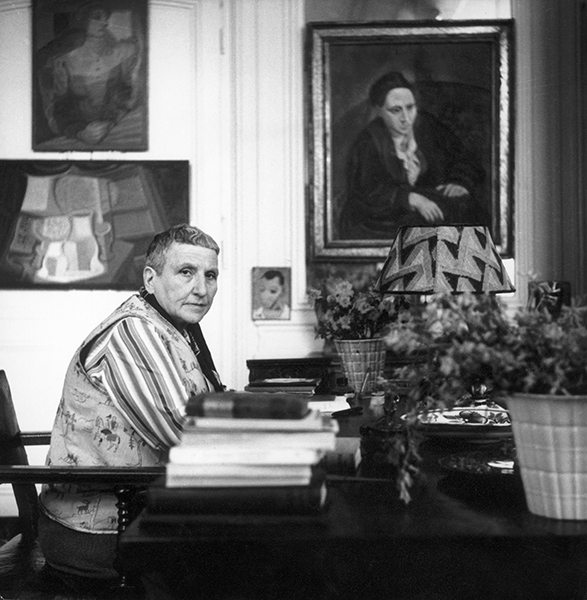

Gertrude Stein and the Bergsonism “to let ourselves live.”

As Lisa Ruddick notes,[1] Gertude Stein's prewar technique rejects selective attention and favors perceptive disinterest or the disintegration of focalization, with the purpose of capturing the so-called stream of consciousness–in other words, an experience in duration. Bergson describes this qualitative duration in beautifully simple terms: “to let ourselves live.”[2] The resulting aesthetic is an aesthetic of time, instituted by what James and Bergson referred to as durational processes. It is important to understand the role of current perception in the constitution of Bergson's aesthetic of time, because understanding what happens as a result of this perception is essential for defining the aesthetic of analytical cubism. What is important in this painting is the dynamic aspect of experience: a succession of qualitative changes that merge, that penetrate each other, without a clear outline.[3] The singularity of this art ties into the constitution of a space-time.

Using a dislocated syntax with unusual superimpositions and discontinuities, analytical writing is built upon what Bergson considers to be the “motor-schema”[4] of a perceived image. Going over its outlines, the memory-image is superimposed upon it like an echo. The undifferentiated way of representing these superimposed images in analytical paintings in turn leads to a perceptive undifferentiation. Lacking a rich enough perception, with the motor tendency apparently being “compressed on site,” the image is not recognized, hence the “ambiguity” that is often criticized in both Picasso's hermetic painting and in Gertrude Stein's prose. In Stein's poems, there is not a sequential, linear progression of thought, but rather a complex mixture of ideas that seep into each other and make up an uninterrupted continuum, a rhythmic flow. And I happen to believe it is no coincidence that this method developed alongside Picasso's analytical painting, precisely evoked in the poem she dedicated to him, A Completed Portrait of Picasso.

[1] Lisa Ruddick, “Melactha and the Psychology of William James”, in Modern Fiction Studies, 28, Issue 4, winter 1982-1983, pp. 545-56. See also Robert Kiely, John Hildebidle, William James and the Modernism of Getrude Stein, Modernism Reconsidered, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1983, pp. 47-63.

[2] : “Pure duration is the form which the succession of our conscious states assumes when our ego lets itself live, when it refrains from separating its present state from its former states (…). » Henri Bergson, Essai sur les données immédiates de la conscience (published in English as Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness), in Œuvres, PUF, Paris, 1959, p. 67.

[3] We will refer to Bergson's definition of duration: “Pure duration might well be nothing but a succession of qualitative changes, which melt into and permeate one another, without precise outlines, without any tendency to externalize themselves in relation to one another, without any affiliation with number: it would be pure heterogeneity.” Ibid., p. 70.

[4] Henri Bergson, Matière et mémoire. Essai sur la relation du corps à l'esprit (Matter and Memory), Paris, 1896. See also Michel Leflot, Idées de Bergson tirées de son livre “Matière et mémoire : Résumé — Éclaircissements, Éd. de Broca, Paris, 2010, p. 37ff. Haut du formulaire

Bas du formulaire

Summary

Summary