Kahnweiler, the only Picasso dealer after the war, and the Louise Leiris gallery, rue de Monceau.

Once he was reconciled with Picasso, the friendship of their youth changed over the years, taking on the form of a touching connection, much like a family bond. In fact, Kahnweiler's wife Lucie Godon was also the sister of Bero (Berthe) Godon, who married the artist Elie Lascaux. They had met at one of the "Boulogne Sundays," an informal social salon of sorts held by Daniel-Henri Kahnweiler at his home in Boulogne from 1921 to 1927 and organized by Juan Gris, which ended when Gris died. Elie Lascaux attended the gatherings as one of the gallery's artists. Elie and Bero had a daughter, Germaine, who later married Xavier Vilató, one of Picasso's nephews, also a painter.

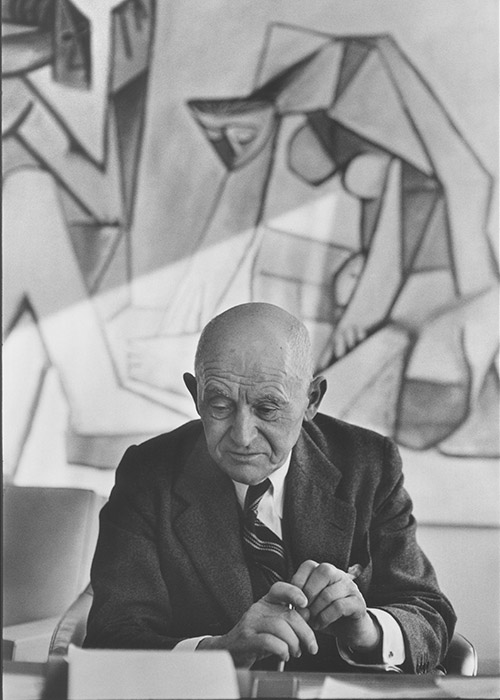

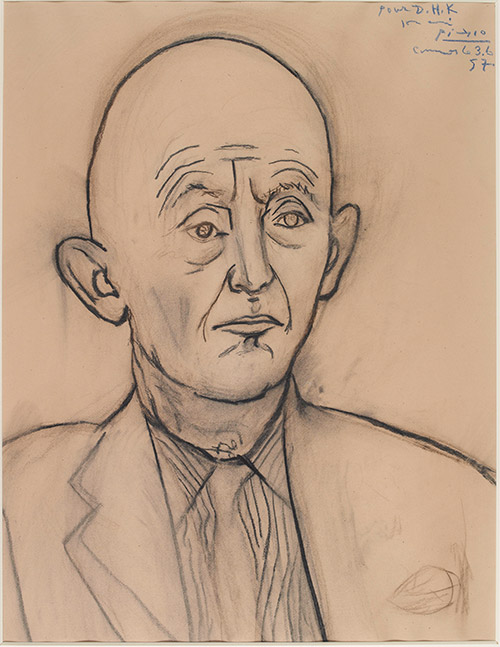

Considered the discoverer of Cubism, Kahnweiler traveled around the world attending invitations and giving lectures, while Louise Leiris ran the gallery that had borne her name since the Second World War. Louise, who married Michel Leiris in 1926, was actually Lucie Kahnweiler's secret daughter (and was passed off as her younger sister for many years). Therefore, Michel Leiris was also linked to Picasso. His presence and his erudition breathed new life into Picasso and Kahnweiler's relationship. In 1957, the Louise Leiris gallery moved to Rue de Monceau. In the venue designed by Charlotte Perriand, Picasso presented his latest works, painted between 1955 and 1956. That exhibition at that location symbolized the strength of the bonds between all those involved. From that moment on, Louise Leiris held a dozen Picasso exhibitions, at a rate of one (or even two) each year.

Kahnweiler became Picasso's only dealer.

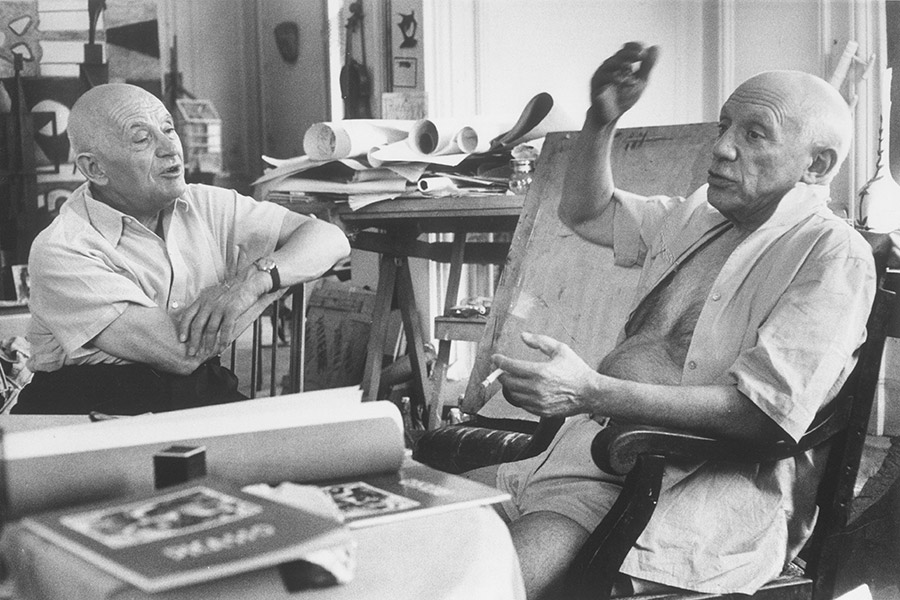

Their relationship has been discussed many times for having been so unique and unusual. "Are you coming to charm me or to piss me off?" That was how Picasso answered the phone when his dealer called to announce his visit for the next day.[1] They were so different! Clearly the dealer was fascinated. For him, all of Picasso's art was a form of confession. The painter was constantly searching, teeming with ideas, dominating. Even so, their relationship lasted sixty-five years —with its ups and downs, of course, but they never parted ways and both acknowledged the sincere, indestructible friendship they shared. "What is even more extraordinary is that their relationship was able to last while one of them (Kahnweiler) stuck firmly to his principles, remaining faithful to his approach down to the smallest of contradictions, whereas the other (Picasso) never ceased to evolve and change, superimposing new contradictions over the former ones."[2]

Picasso died six years before his friend and dealer, his faithful companion, who passed away in 1979.

Summary

Summary