"Dreams and lies of Franco" then "Guernica" in 1937, cries and politics

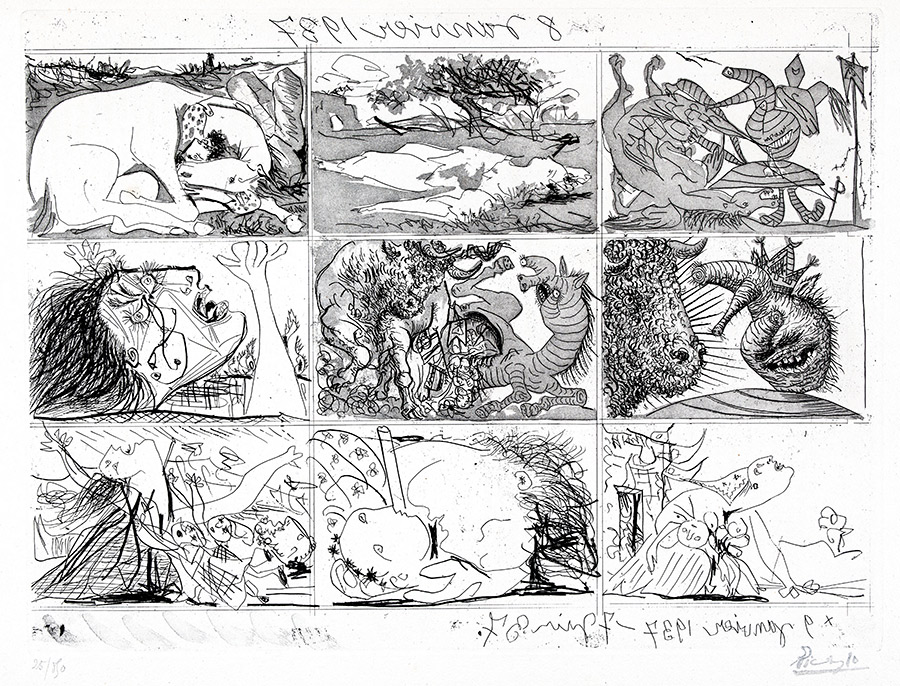

Picasso's first political reaction, after January 1937, was an unfinished series of prints on two plates, The Dream and Lie of Franco, through which the artist intended to perform "an act of execration against the attack on the Spanish people."[1] Picasso had planned to print postcards supporting the cause, but the project never materialized.

"There are fourteen scenes on two plates with nine each (for a total of eighteen; I'll tell you what I did with the last four). In the first nine scenes of the first plate, Franco rides a ridiculous charger, walks on a tightrope, attacks a beautiful statue with a pickaxe, is charged by a bull, prays before the altar of money (the Host is replaced by a coin), and rides a pig. In the first five scenes of the second plate, he isn't always present. In the first, he kills Pegasus, but doesn't appear in the next two, which are very beautiful: one depicts a white female figure stretched out on the plain; the dead Pegasus has turned into a woman. In the following scene, the woman becomes a sleeping horse. Franco reappears as a carrot laughing at a wise bull. In the last scene, the bull gores Franco, who has the body of a zebra. As you can see, it isn't boring. I used the four remaining panels while I was painting Guernica, to engrave details for Guernica."[2]

While he was working on Guernica in April and May, 1937, Picasso made his first political statement: "The war in Spain is the conflict of a reaction against the people, against freedom. My whole life as an artist has been nothing more than a continuous struggle against reaction and the death of art. In the panel I am working on, which I will call Guernica, and in all my recent works, I clearly express my abhorrence of the military caste that is sinking Spain into an ocean of pain and death." Picasso was looking for possible approaches to his commission for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 International Exposition in Paris. Witnessing the huge collective emotion spurred by the bombing of the civilian population—which caused the death of over 1500 people on a market day at the Basque village that gives the painting its name—Picasso, horrified and deeply moved, worked furiously on the piece in preparation for its final execution. By naming it after the devastated village, he ensured that the piece would be understood in political terms, unequivocally condemning fascist brutality.

However, once it was shown in the Spanish Pavilion, Guernica disappointed those who expected a call to arms.

Summary

Summary