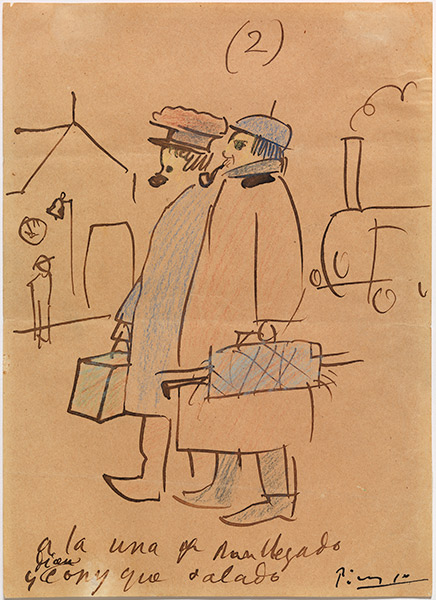

Picasso, “The Foreigner”

An impressive account not only of the artist’s life, but also of a century in the history of France, with its ideas and conflicts, Annie Cohen-Solal’s book reads like a novel as her fluid prose takes the reader on an extraordinary journey. The author’s aim here is to show the difficulties, the bureaucratic obstacles and the disappointments faced by foreigners who settle in France. Despite the fame he achieved during his lifetime, Picasso was not spared the annoyances and harassments of supercilious civil servants. He was “trailed” from 1901 onward by the French police intelligence service, which built up a file as the political events unfolded (no. 76.664, foreigner file, police headquarters, Directorate General of the Police), reporting on his different inquiries and their responses. Annie Cohen-Solal has carried out extensive research—for example, tracking down the author of the fateful May 25, 1940 report whose highly critical and violent content prevented the artist from obtaining French citizenship further to his formal application. Picasso was even considered “suspect” according to the criteria of the time.

The author tells us about Picasso's opinions, his questions, his distress at times, his difficult beginnings, his friendships, his political choices and the ways in which his work evolved. She conveys the enthusiasm of young museum curators, such as Alfred Barr in the United States, and the reluctance of the French institutions to acknowledge the talent of this decidedly “foreign” artist who sought to challenge the established academic painters. Ruthless critics, skeptical politicians, baffled exhibition visitors—Picasso was spared none of this while his reputation continued to grow around the world.

In the course of her research, Annie Cohen-Solal gathered notes, testimonies, letters, published memories, and photographs, sharing her excitement with us upon each discovery. Was Picasso's behavior determined by his foreign status? At times, for sure, especially during the dark period of the Occupation, which was particularly difficult for “foreigners”—and in his case, even more so, given his support for the Spanish Republican cause.

First considered an anarchist and then as a troublesome communist, the authorities kept track of him as a suspect. After being excluded from French public collections until 1947, “comrade” Picasso, in high demand after his affiliation to the French Communist Party in 1944—which was deftly promoted by the Party itself—donated paintings and drawings to the cities that requested them. In 1947, Jean Cassou (the director of the Musée national d’Art moderne) and Georges Salles (Director of the French museums administration) finally managed to include Picasso masterfully in the Musée national d’Art moderne, along with other contemporary artists who had been ignored by the institutions until then. Deeply affected by the chilling contempt to which he had been subjected by the administration, Picasso sought his revenge: he chose the ten works that he considered most representative of his personal development and donated them, refusing the amount proposed for their acquisition at a time when he no longer had any need for it. That help would have made such a difference decades earlier...

True to his friends and his convictions, Picasso lived through the century experiencing the vagaries of history. This book reveals the unenviable position of being an outsider in a foreign country. Through this exceptional journey, the entire migration policy reveals its little secrets, from its infamies to its strict rules and regulations.

Annie Cohen-Solal, Un étranger nommé Picasso, Editions Fayard, 2021, 730 pages, €28.

Summary

Summary