> Where art wins over reality.

The stereotypes that Picasso elaborated in Gósol can also be listed in fifteen cases. Let’s focus on them through the works mentioned in the previous section and through some others Gosolian works.

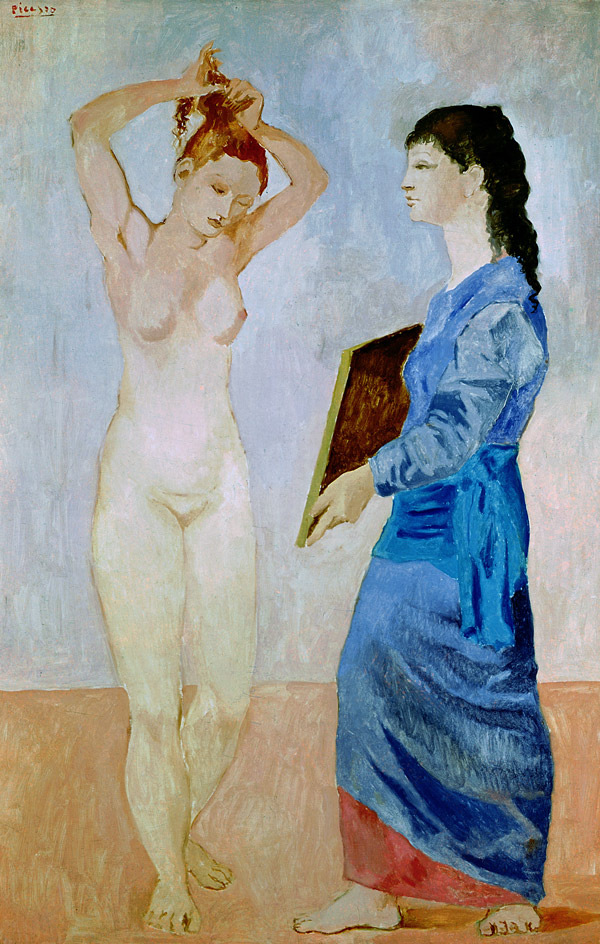

1. Standing with raised arms (Toilette with light background)

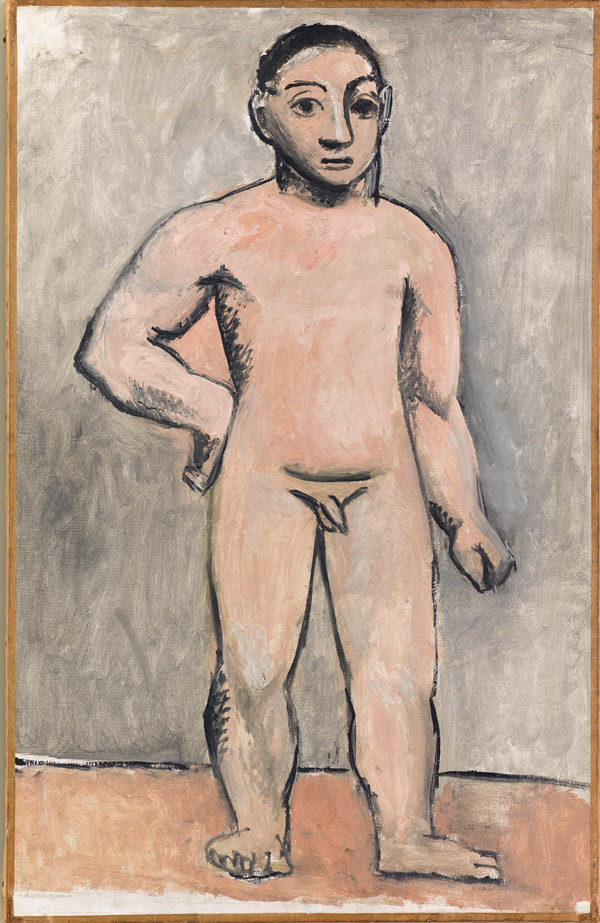

2. Forefinger and thumb extremely thick (Naked boy)

3. Presentation of the nape of the neck with hair usually half tied (this is the case of female figures, who are the most common) and showing a quarter of the face, just enough to display the split of an eye, which cannot be seen, and an ear (Girl torso)

4. Feet disproportionately big and with a very rustic trace compared to the rest of the figure, without distinguishing between the sizes of the toes, which are delimited by a very thick outer line and placed on the same horizontal line (Naked boy)

5. Eyebrow as a simple, well-shaped arch above the eye (Woman with Loaves)

6. Nose as a “Z” shape that unifies an eyebrow, the nose and one of the nostrils (Woman with Loaves)

8. Prominent line bar which unifies the lower center of the nose with the upper center of the lip (Woman with Loaves)

9. Vulva as a simple triangle (The Hairstyle)

10. Eye in a Romanesque aesthetic (Gosolian boy)

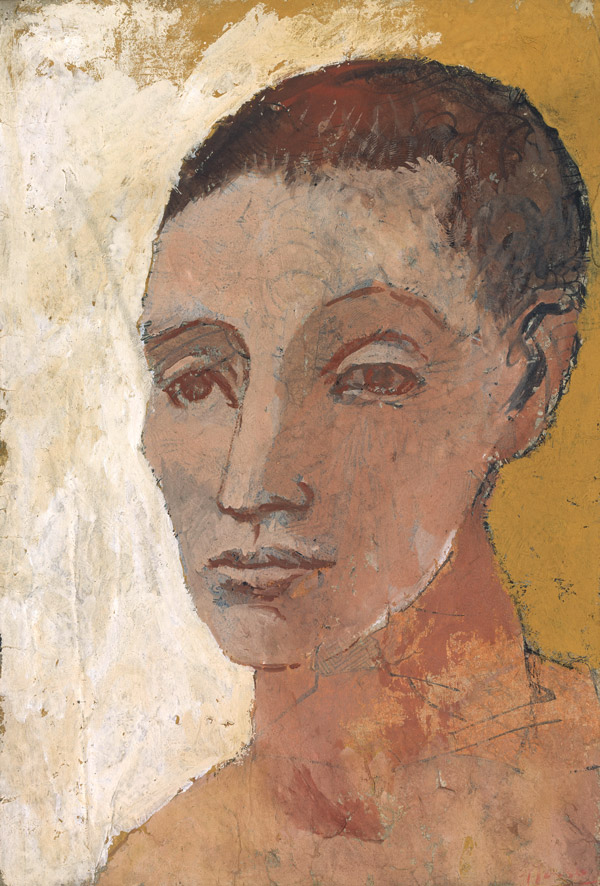

11. Oval in an Iberian aesthetic (Woman with Loaves)

12. Chin: following the oval stereotype, with a massive and heavy chin (Nude Female standing)

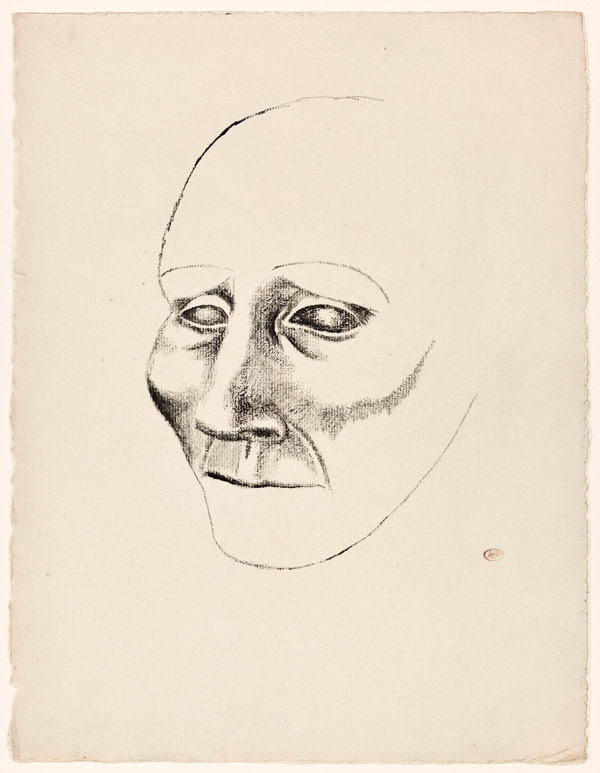

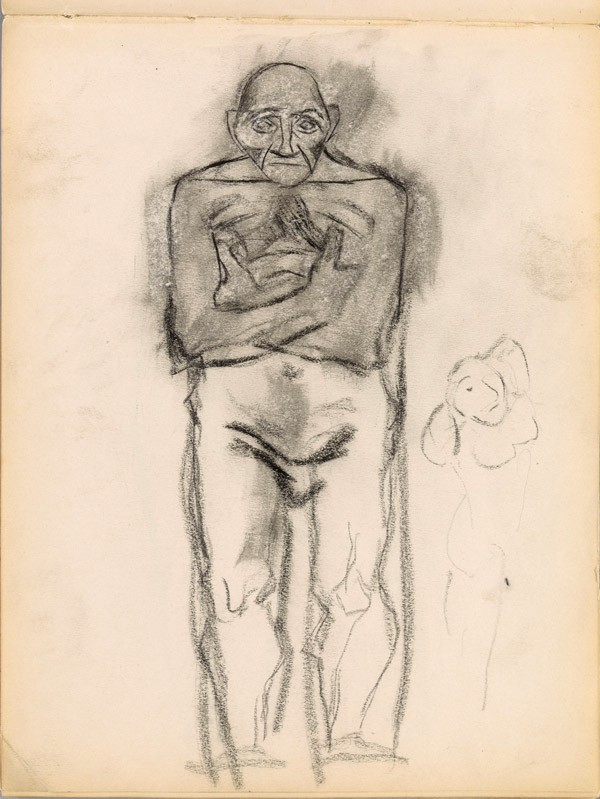

13. Collar bone stereotype as a single line that goes from one shoulder to the other (Josep Fondevila - Study).

14. The mask. Picasso had worked on Josep Fondevila’s face and turned the oval stereotype into the masque stereotype as the most fruitful plastic solution to go into the motif of Gertrude Stein’s Portrait (Masque). Here, the oval, eyebrow, and eye stereotypes converge.

15. The masque also includes a stereotyped fold, consisting of two lines, which connect the nose wings to the corners of the mouth.

Picasso arrived in Gósol with Cézanne’s doubts in mind. However, unlike his master, he did not confront them via obsessive attention to an external landscape, but rather via obsessive attention to a human landscape. This was the testing ground for his stereotypes. The facemask of Fondevila was a “trampoline for research to the depersonalization of the face”,[1] and would become the structure for Gertrude Stein’s face (see Fig. 18 and Fig. 19).[2] It would become the presence of the motif in the absence of the model: Gertrude’s face (Fig. 19) was usurped by Fondevila’s mask (Fig. 18). In this pictorial event, presentation won the battle over representation, the motif won over the subject, and art won over reality.[3]

In this regard, it must be said that the simplicity of the Gosolian palette –with its ochre tonality and fitting presence of a special kind of Gósol blue (totally different from the blue of the Blue period and coming from the outline of the Gosolian windows)–, is the only chromatic proposal that Picasso’s privileged plastic intelligence could conceive for the process of stereotyping forms, a process that would by no means have allowed color profusion. Likewise, such profusion had not been allowed by Zurbarán, nor by Velázquez, nor by Goya. For all three, ochre was the degree zero of color, like it was for Pau de Gósol. It is too easy to see this as an essential part of the Spanish pictorial tradition, in so far as ochre was also Rembrandt’s and Cézanne’s chromatic place. Instead, I argue that ochre was an audacious strategy for all of these revolutionary painters to reach the originality of the return to the origin, which was the reason for Picasso’s life-long dedication to making variations of their work. Certainly, the originality of the return to the origin was, paradoxically and from Gósol to his death, Picasso’s most significant engagement to exercise his peculiar and inexhaustible Modernity. And ochre, as the color of the Gosolian icons and becoming one of the main chromatic places of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, was a way to practice the return to the origin in a modern way of making.

With the finding of the stereotypes in rolled-up monochrome canvasses, at the end of July 1906 Pau de Gósol crossed the Catalan Pyrenees, riding a male mule towards Puigcerdà, then a stagecoach towards Aix-les-Termes, where he would take the train to Paris. He had reborn as Pau from Gósol and as Cezanne’s grandson three months before the master died. It was like taking on the baton in a remote place, through a sort of magical act of legacy, after which Picasso was fully aware that he had begun his journey towards his peculiar form of Modern Art. The Portrait of Gertrude Stein and The Demoiselles d’Avignon proved him right.

[1] This is according the Brigitte Léal’s expression in “The Sketchbooks from the Rose Period”, in Picasso, 1905–1906: De l’època rosa als ocres de Gósol (Barcelona–Bern: Polígrafa, 1992), 97–105, see especially p. 102.

[2] Richardson states: “If there are no drawings for the repainting of Gertrude’s Stein portrait, it is because they are all of Fondevila. The old smuggler lives on in her guise”, Richardson op. cit. vol I: 453. See also Marilyn McCully, “Chronology,” a Marilyn McCully (Ed.), Picasso. The Early Years (see note 38): 50.

[3] It is my understanding that this is the sense of Picasso’s statement in response to the adverse reaction of the first people who saw Stein’s portrait, which recriminated him that it did not resemble the model. Picasso answered: “Ne vous en faites pas, elle s’arrangera pour lui ressembler” (“Don’t worry, she’ll try to look like it”, Pablo Picasso, Propos sur l’art, note 13: 159).

Picasso, Face-mask of Josep Fontdevila, 1906, Musée national Picasso-Paris.

Picasso, portrait of Gertrude Stein, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Picasso : Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1907, MoMa, New York.

Summary

Summary