> Picasso’s new plastic language

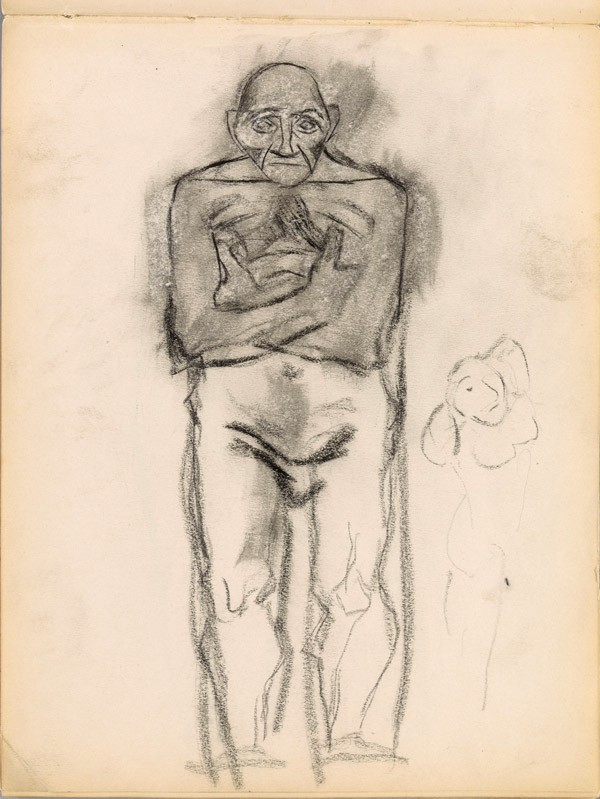

Enric Casanovas was a sculptor from Picasso’s circle of friends in Barcelona. He used to go to Gósol because he was also a keen excursionist. He completed several stages of his work there. Casanovas would warmly recommend the Pyrenean town to his friends and so he did to Picasso, who decided to stay there for several weeks before heading to Paris. As a matter of fact, it would seem than the sculptor initially intended to travel with Picasso but was impeded to do so by his mother’s illness. Immersed in the austerity of life in Gósol, Picasso tried to obtain from him tools to work on sculptures made of wood (boxwood) and Ingres paper, as clearly worded in a letter from June 27th – in which Fernande also makes a strange order: two candied oranges glacées,[1] along with cosmetic products (mainly, her favorite perfume: Eau de Chypre), ordered before[2]– and in another letter sent a few days later, he signs with the famous “tu amigo dit el Pau de Gósol”. [3]

Finally, the tools and paper requested by Picasso never arrived. He himself gave up the orders made by Fernande in a non-dated letter[4] in which Picasso says they would leave the village in a few days, probably because he had overcome his creative block. Picasso requested Casanovas to remain silent about his return to Paris. This was probably due to Picasso’s eagerness to finish Stein’s portrait once the pictorial findings of Gósol has been established. This suggests that what really happened in Gósol was the preparation of an audacious and definitive journey: Picasso’s vertiginous transition towards a new plastic language, and with it, towards modern art. The little town was simply the marvelous original setting (in the sense of a proto-genesis, that is: the ultimate beginning of a story)[5] for this great adventure, probably the best setting that Picasso, an urbanite with non-sophisticated manners, could ever have imagined. This was the ecosystem where he renamed himself “Pau”, moving closer to Cézanne’s first name (Paul), like a pilgrim being reborn at his first and troubled step on the way to himself.[6] In this rebirth, Gósol was not only an austere setting, close to nature, but also the place where Picasso experienced for the first time two of the so-called primitive[7] aesthetics that gave him the keys to his peculiar modernity: Romanesque primitivism and Iberian primitivism, one year before his discovery of what was called at that time art nègre. Furthermore, it could be said that Pau de Gósol returned to Paris with the awareness of having found a new and definitive origin to his creative process, responding to the etymology of “primitive” as that which does not have a previous origin and that gives birth to everything that stems from it. The following section details the terms of this creative rebirth.

The day he returned to Paris from Gósol, Picasso arrived at the Bateau-Lavoir and, in a strange outburst of security and maturity, he finished the portrait of Gertrude Stein without model and very fast:[8] he had found how “to go into the motif”. He devoted the following eleven months to the frantic preparation of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, painted definitively between June and July 1907, one year after his stay in the small Catalan town in the Pyrenees. Picasso’s route to modern art started from a place completely removed from the rhythm of modern time but dealing with a primitive everyday life that became for him the origin for this route. He took this path without a speck of regret. A hundred and fifteen years later, it seems this was the implacable and fascinating route of a destiny.

[1] See Portell i Camps, Les Cartes, see letters 36, 149-50. In Gósol, Picasso made two boxwood sculptures: Nude with raised arms, Musée Picasso, Paris, and Bust of Fernande (with touch-ups of painting), Musée Picasso, Paris. The tools he ordered never made it to Gósol, and this contributed to the rustic charm of these boxwood sculptures.

[2] See Portell i Camps, Les Cartes, letter 34, 148-9.

[3] See Portell i Camps, Les Cartes, letter 38, 151-2.

[4] I disagree with the usual dating of this letter by art historians, see for example Portell i Camps, Les Cartes, letter 39, 152-3. Here, the compilers it on Monday 13th of August, but with the precisions I have made about Stein and Picasso correspondence –see note 5 –, in my view it was written the last Monday they were in Gósol, probably on July 22th.

[5] See Jèssica Jaques, “Gósol and the picassian proto-genesis”, Bleu et Rose, (Paris, Musée Picasso Paris – Musée Orsay, 2018). See also “Carnet Catalan”, Les carnets de Picasso, Museu Picasso de Barcelona, 2020, pp. 341-363.

[6] Even it is somewhat anachronistic to remind this fact here, let us not forget that fifteen years later, Pablo Picasso would rename his first son Paulo, a name which allows to concentrate phonetically in a single word “Pau + Paul + Pablo”.

[7] On Picasso and primitivism, see the catalogue Picasso Primitif (Paris: Musée du Quay Branly, Flammarion, 2017). For the foundational text on primitivism in general and that of Picasso in particular, see William Rubin (ed.), catalogue to the exhibition of Primitivism in 20th Century Art, (New York: MoMA, 1984). Nevertheless, in this text Picasso’s primitivism is dated after the stay in Gósol, probably because at the time the catalogue was written, the Gósol works were still relatively unknown. See also, among other works of the same author, Pierre Daix, Le nouveau dictionnaire Picasso (Paris: Éditions Robert Laffont, 2012), 756–63.

[8] Gertrude Stein insists it was in a single day, The Autobiography, 717. See Richardson, A life of Picasso, Vol. II. 52.

Summary

Summary