> Cézanian syntax applied

In Gósol, the first of Picasso’s testing grounds for his Cézannian doubts were the portrait and the still life,[1] two genres renewed by the Master of Aix, who converted them into the most fruitful place to play out the tension between the everyday and the strictly pictorial. In fact, the pictorial transformed the primitive everyday into a privileged place to release painting from the yokes of narrativity, naturalism, and illusionism. In the Pyrenean town, Picasso followed the procedures of this liberation one by one,[2] experimenting with the originality of the return to the origin of certain aesthetics, such as the Romanesque and the Iberian, as well as rearranging his complicated “imaginary museum”.[3] The Cézannian syntax that he practiced involved some well-defined ways “to go into the motif”, of looking towards pictorial presentation and rejecting representation, making modern art from a non-evasionist primitivism.[4] We will focus on fifteen of these ways through fifteen Gosolian works. Figs. 1–4 can be considered as the first modern works by Picasso.

- Vindication of the repetitive (The Harem, Fig.1)

- Asymmetry (as in Woman with Kerchief –Fernande–, Fig. 2)

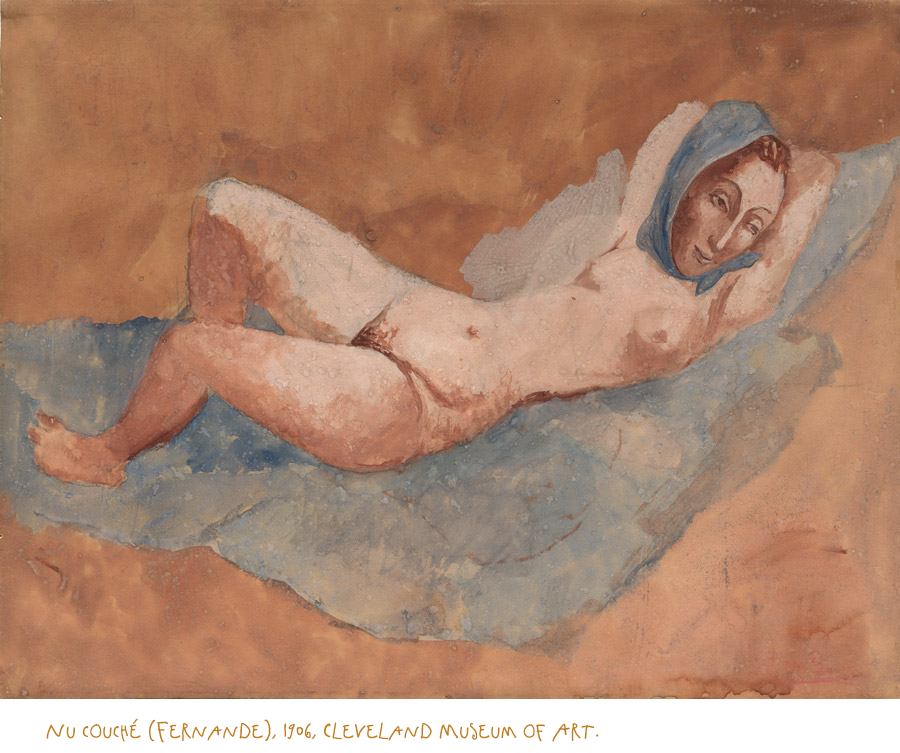

- Dislocation (Reclining Nude –Fernande–, Fig. 3)

- Conversion of figures in icons (Woman with Loaves, Fig. 4)

- Revitalization of artistic archaisms with a new and anti-illusionist gaze (Two Youths, Fig. 5)

- Binding of form and background against the continuum (The Peasants, Fig. 6)

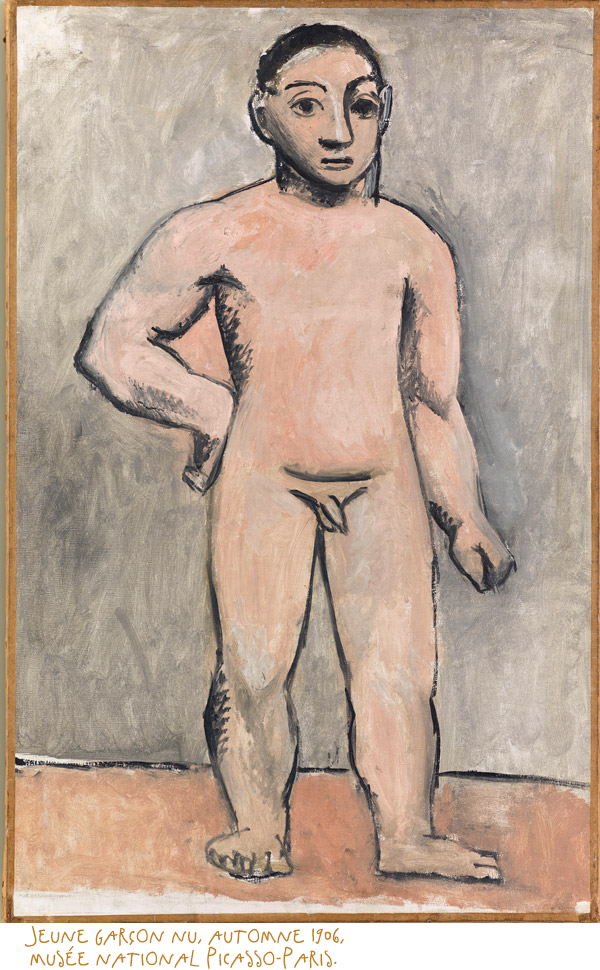

- Tension between frontality and depth along with the emphasis of contours (Naked boy, Fig. 7)

- Elimination of the anecdote and the narrative as well as emphasis on contours (Girl Torso, Fig. 8)

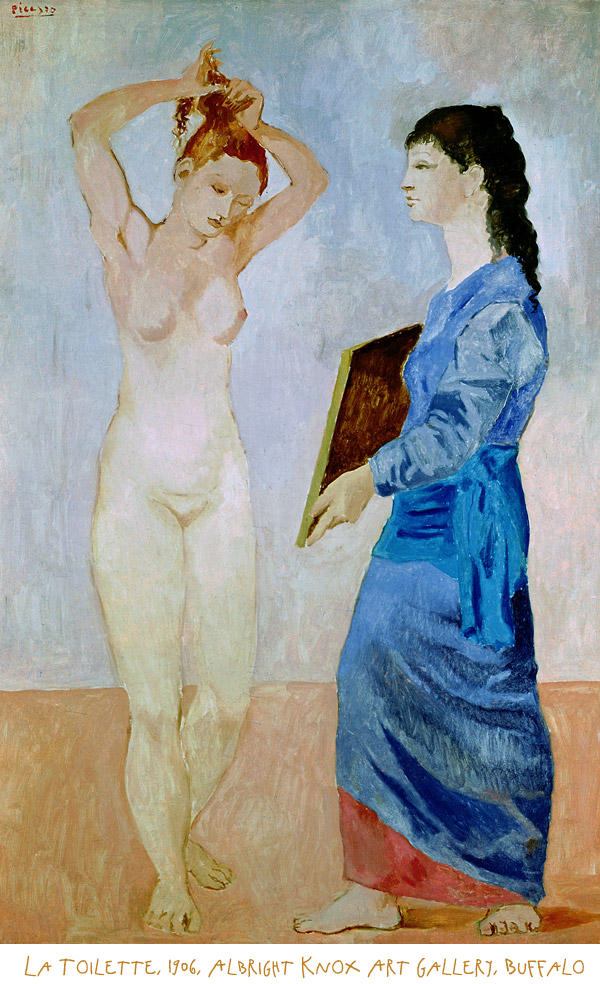

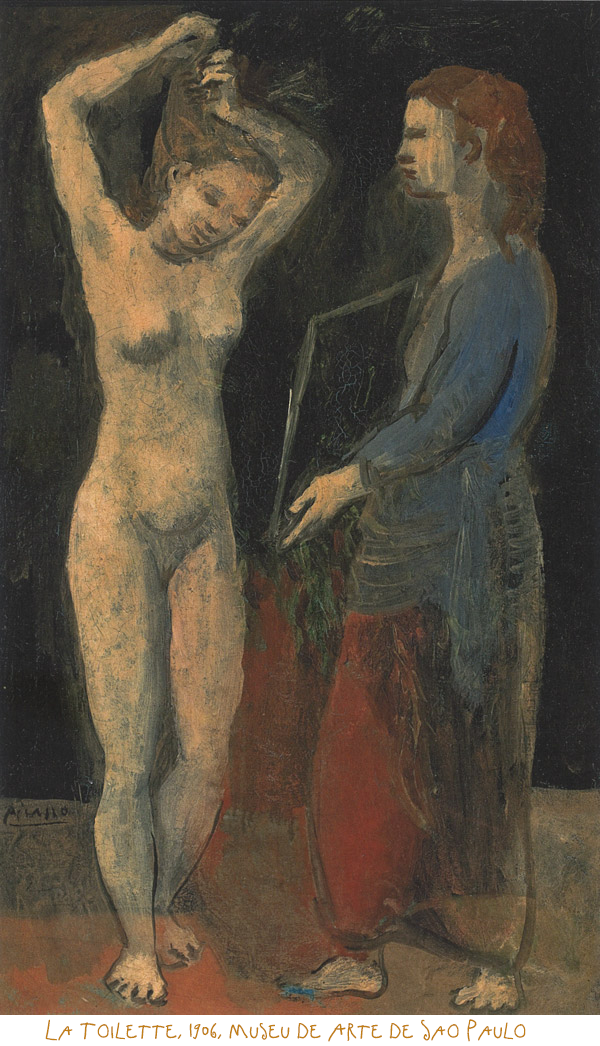

- Emphasis on simplification through the stereotype (The Toilette, Fig. 9),

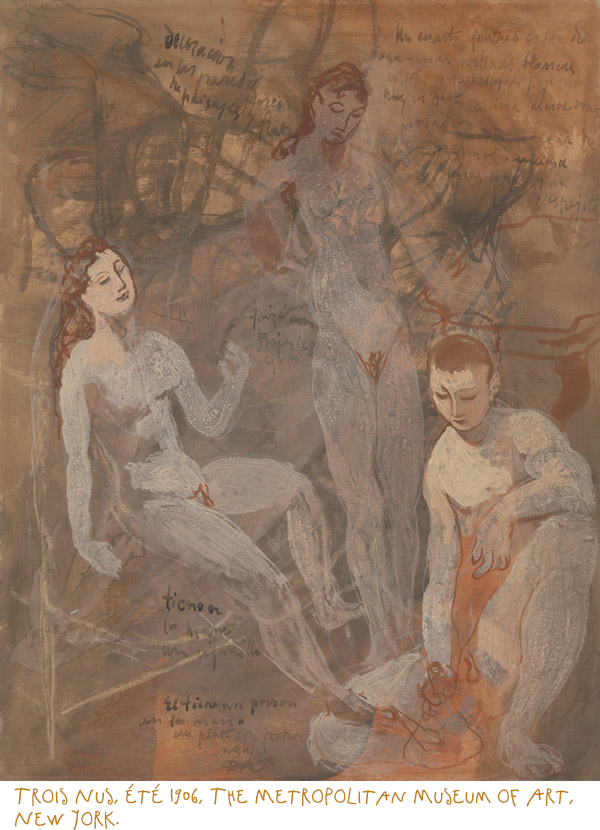

- Vindication of the unfinished (Three Nudes, Fig. 10)

- Conversion of scenes into scenarios (Girl and Goat, Fig. 11).

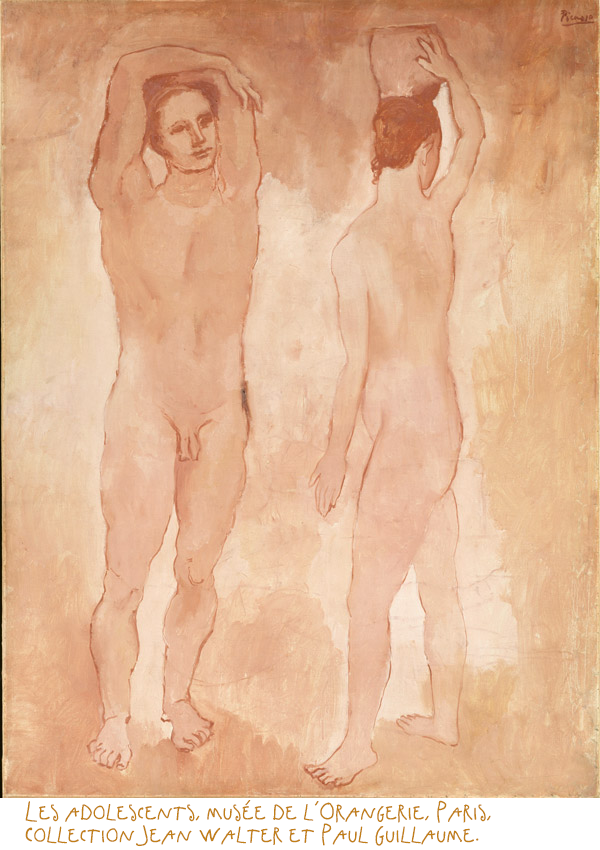

- Treatment of figures as objects (The Adolescents, Fig. 12, concerning to the right figure).

- Plurality of viewpoints and disturbance of the gaze (The Hairstyle, Fig. 13) [5]

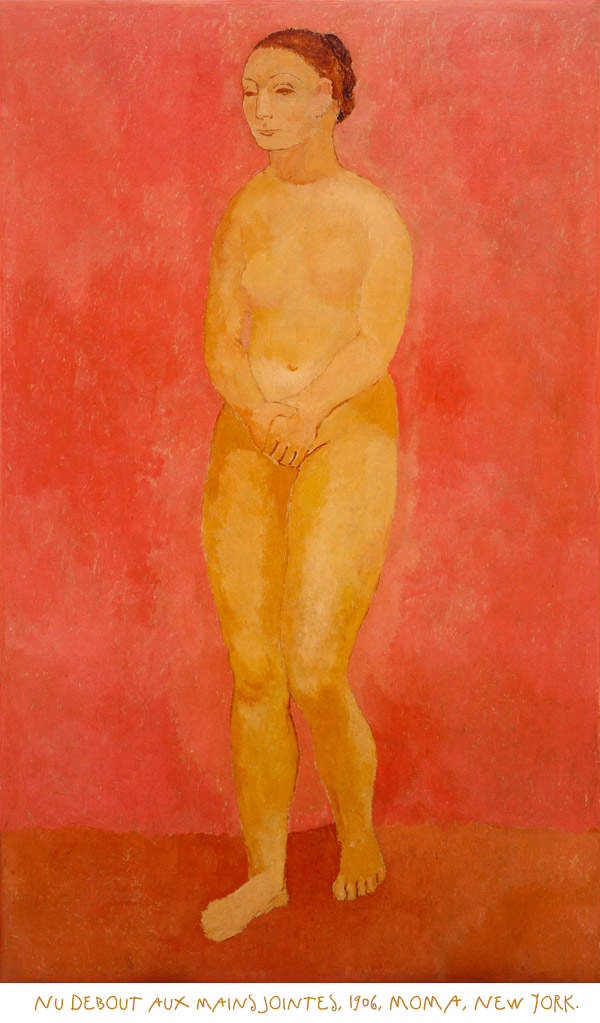

- Choice of the sculptural and monumental through a structuralizing and constructive brushstroke (Standing Female Nude, Fig. 14),

- Process of anonymity and estrangement (The Toilette with dark Background, Fig. 15)

These fifteen ways of “going into the motif” converge in the Portrait of Gertrude Stein and in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon which must be considered, to a large extent, as Picasso’s tribute to Cézanne (especially to Madame Cézanne with Fan and to the several versions of The Bathers). This convergence shows how, already in the summer of 1906, Pau de Gósol claimed the inheritance of Paul Cézanne. This, however, was only the beginning of the story of this peculiar genealogy. Picasso adopted Cézanne’s plastic gestures as naturally as sons inherit their parents’ gestures, and he exercised them every time his obsessive experimentation brought him to unknown places, like a man who knows that he can go back home after leaving.[6]

The Cézanne-Picasso lineage began in Gósol (1906), passed again through Horta de Sant Joan (1909)[7] and ended in Vauvenargues (mainly from 1959 to 1961). Pau de Gósol, Pablo Picasso and Paul Cézanne diluted over an almost sixty-year route that took Picasso from his birth as a modern painter at the Pedraforca to his burial on the northern face of Mount Sainte-Victoire, not far from Cézanne’s tomb. In Vauvenargues, Picasso had four magnificent Cézannes for the same reasons that when he was seventy-eight years old he bought the “real” [8] Sainte-Victoire: because he wanted to be Cézanne’s grandson, [9] even if he had to buy the estate.

Picasso’s trip to Gósol took place forty-four years before his retirement in Vauvenarges, and was highly foretelling. In 1906, the Pyrenean town was also a place of austere solemnity (as, in fact, it still is today). Picasso only stayed there for eight weeks, yet three hundred and two works (counting everything he produced) are attributable to this period.[10] These works include around twenty oil paintings and several gouaches. They were the grounding revolution for Picasso’s forthcoming work, as they were, on the one hand, a radical and almost violent abandonment of the Rose and Blue periods, i.e. of – let us say – everything that happened before and, on the other hand, a privileged moment of plastic discoveries for all that came after, especially for the Portrait of Gertrude Stein and for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.[11]

[1] On the relationship between Cézanne’s and Picasso’s still lives from the years 1906–7 see: Elisabeth Cowling, “Le drame de l’homme”, 34–54, see specifically 48–52.

[2] This liberation also had its moments of a negative dialectic from Picasso towards Cézanne, since Picasso was trying to emancipate himself from following the master of Aix in an excessively scholarly manner as well as from the standstill in what Stein termed his failures (see note 26). On this issue see Denis Coutagne, “Contre Cézanne,” 221–8.

[3] Iberian aesthetics was also embodied in a Enric Casanovas’ sculpture dating from 1907, being its location currently unknown. See Susanna Portell (Ed.), catalogue Enric Casanovas. Escultor i amic (Girona: Fundació Caixa de Girona, 2008), 27. On this sculpture and on the intersection between primitivism and modern art in Catalunya at the beginning of the twentieth century see: Teresa Camps, “El nostre primitivisme,” in “L’avantguarda de l’escultura catalana” (Barcelona: Centre d’Art Santa Mònica, 1989), 3

[4] This view is akin to the one by Pierre Cabanne, Le Siècle, chap. IV: “Montmartre et le Bateau-Lavoir”, 236–43.

[5] Work probably began in Gósol and finished in Paris.

[6] As witness of this peculiar lineage, note that Picasso, in his advanced age, zealously kept in his bedside table a letter that Cézanne addressed to his son. See Bruno Ely, “Le château de Picasso à Vauvenargues,” in Billoret-Bourdy and Guérin (Eds.), Picasso Cézanne, 193–203 and “Picasso, la période de Vauvenargues,” in Billoret-Bourdy and Guérin (Eds.), Picasso Cézanne, 231–65.

[7] Being there for the first time in 1898.

[8] When Picasso bought the Vauvenargues castle in 1958, he told Kahnweiler on the phone that he had bought “Cézanne’s Sainte-Victoire”; when the art dealer asked him which one, Picasso answered “la vraie” (“the truly one”). See Ely, “Hommage de Pablo Picasso”, 193–203, especially 196.

[9] On Picasso’s willingness to be “Cézanne’s grandson” see, Daix, Dictionnaire, 181 on his willingness to be “Cézanne’s son” and the protégé of his spirit: Brassaï, Conversations, 104.

[10] For the moment, the complete catalogue can be found at the end of my book Picasso, un verano para la modernidad. This book includes information from: Georges Boudaille, Picasso première époque 1881–1906. Périodes Bleue et Rose (Paris: Musée Personnel, 1964); Douglas Cooper, Picasso. Carnet Catalan (Paris: Berggruen, 1958); Pierre Daix, Picasso, dibujos 1899–1917, Catalogue to the Exhibition of the IVAM in Valencia (Valencia: IVAM, 1989); Pierre Daix – Georges Boudalle, Jean Rosselet (col.), Picasso 1900—1906: Catalogue raisonné de l'oeuvre peint (Neuchâtel: Éditions Ides et Calendes, 1966, reprinted in 1988); Arnold Glimcher, Marc Glimcher, Mark Pollard, Je suis le cahier. The Sketchbooks of Picasso (New York: Pace Gallery, 1986). Marilyn McCully (Ed.), Picasso. The Early years (Washington: National Gallery: 1997); Josep Palau i Fabre, Picasso vivent. 1881–1907 (Barcelona: Polígrafa, 1980); Werner Spies, Picasso Sculpteur (Paris: Artemis –1983–, 2000) ; Christian Zervos, Pablo Picasso. Vol. I: Oeuvres de 1895 à 1906. Vol. 2*: Oeuvres de 1906 à 1912, 1942. Vol. 2**: Oeuvres de 1912 à 1917 (this volume contains a supplement with the works from the period 1906 –1917). Vol. 6: Supplement aux volumes 1 à 5 (1970). Vol. 22: Supplément aux années 1903–1906 (Paris: Éditions Cahiers d'Art, respectively 1932, 1942, 1970); Christian Zervos, Dessins de Picasso 1892–1948 (Paris: Éditions Cahiers d'art, 1949); Catalogue Picasso 1905-1906. (Museu Picasso de Barcelona; Kunstmuseum, Bern: Barcelona, Electra, 1992).

[11] In reference to this use of “before” and “after” see Stein, Picasso, 16 and 22.

Summary

Summary