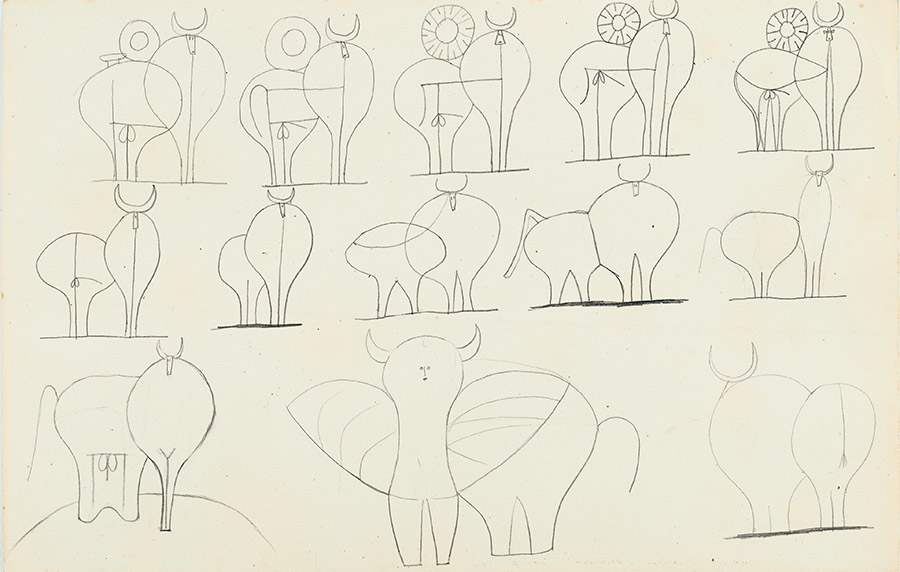

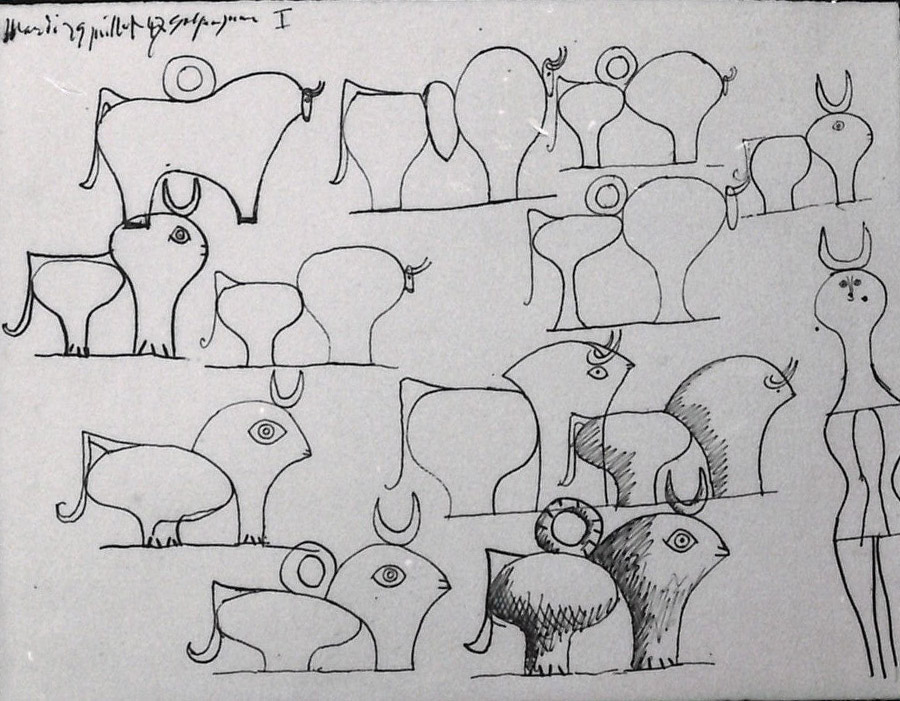

There are four large sheets dated July 29, 1947, full of pen-and-India-ink sketches by Picasso (Figs. 2, 6-7, 9). These sheets are not signed, but they are dated by the artist. In addition, Picasso numbered them from I to IV and added the note “Golfe Juan,” where he had recently settled with Françoise Gilot and their son Claude, born on May 15, only two months earlier. Each sheet is dominated by a subject which is developed in several studies, as well as a second subject that announces the sketches on the following sheet. The first sheet focuses on the theme of the bull and includes a drawing of a centaur, the subject of the second sheet. On the third sheet, the centaur is transformed into a fauness-siren, with a drawing in the center showing a woman in profile; she, in turn, is the focus of the fourth sheet, in which this last subject is further explored and depicted in a frontal view.

The Bull

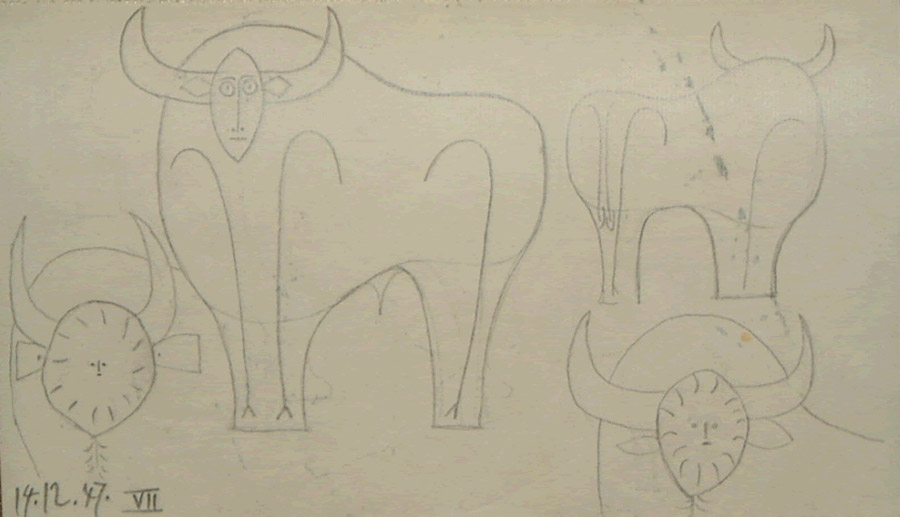

With the bull, the main subject of the first sheet dated July 29, 1947, Picasso resumed the form he had begun in his drawings of September 13, 1946 (Fig. 3) in which the body is represented by an assemblage of two inverted vases. This option was further pursued in his small sketches drawn on the bottom row of the second sheet, dated July 29 (Fig. 6), which led to the drawings dated December 14, 1947, in which the signs suggesting a vessel are absent (Fig. 4). Picasso also did away with the ring that appeared in some of his previous preparatory sketches, the particular sign of a traditional pottery vessel used to store fresh water, the zoomorphic Spanish fired clay botijo set on a foot (Fig. 23bis). The zoomorphic botijo shape with a circular handle prevails in the first ideas for the form of Picasso’s ceramic pieces (Fig. 23).

In late 1947 or early 1948, Picasso made a bull as a variation of this model. This piece, one of his greatest works in ceramics –currently in the collection of the Musée Picasso in Antibes– uses three vases, two of which are inverted with their mouths facing downward. They are cut out to fit into each other and then assembled and fired in a ceramic kiln, thus forming a sculpture based on elements that had originally been thrown as vessels (Fig. 5).

Following the sketches on the last sheet, the animal is represented without a head: the artist replaced it with a human face, modeled to evoke a mask and pasted on in such a way that it suggests the bull’s movement to the right.

Private collection. Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte, Madrid

© FABA Photo: Eric Baudouin

© Succession Picasso 2020

Chinese ink.

Private collection.

© Succession Picasso 2020

Collection Berggruen. © Succession Picasso 2020

Terracotta vase, turned and assembled elements, brown varnish (spout, handle and neck)

Kanagawa, The Hakone Open-Air Museum

© Succession Picasso 2020.

Zoomorphic botijo, Spain, undated.

Private collection.

White earthenware, decoration added and painted with engobes and oxides.

Picasso Museum, Antibes

© ImageArt, photo Claude Germain.

© Succession Picasso 2020

Summary

Summary