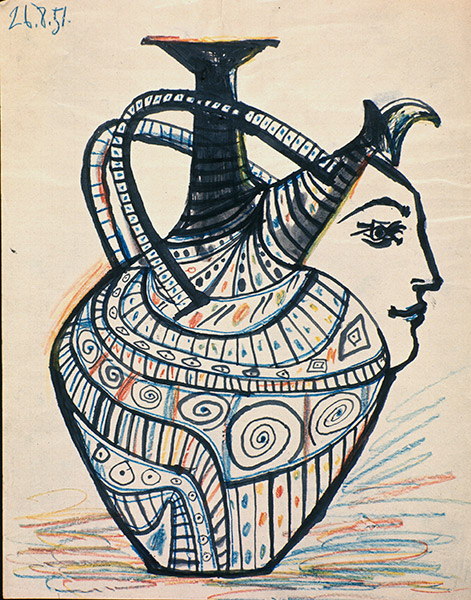

Picasso also produced a number of sculptural ceramics in the shape of women’s heads; in the 1950s, albeit more sporadically, he also explored the association between a human face and a vase. In a large colored pencil and India ink drawing on paper dated 1951 (Fig.27), Picasso anticipated the shape and decoration of a plastic vase with two curved handles derived from the handles on the Cavalier (Fig. 22) and an elegant profile of a woman’s face placed on the spout. The preliminary sketch already proposes a geometric decoration, with horizontal bands, circles, and spirals. We are not aware of any ceramic execution of this drawing, but three years later, in 1954, Picasso remodeled a globular jug and applied paint to endow it with the face of a young girl, applying modeled flowers around the opening and coloring them with oxides under a clear glaze.

Most of the three-dimensional ceramics that Picasso first sketched out in his drawings focus on the themes of animals or the female figure. The only rare exceptions are the studies for decorated vases with a man’s suit dated May 23-28, 1950, which appear to be part of a series of at least four, as marked by the artist on the sheets with roman numerals (Figs. 29-30).

Picasso transferred this decoration with a suit, vest and necktie to a shape invented by Suzanne Ramié and serially produced at the Madoura studio. Thus the artist transformed the “Large vase with two handles and small feet” bringing it to life with a large dose of humor and a sense of caricature, to create the plump-bodied “Man in a suit” (Fig.28). The stenciled oxide painting turns the foot of the vase into the figure’s feet, the body into that of the man, the top of the vase into his head, and the handles into his arms, raised up to his head. Picasso also used this vase shape to transform it into a face and even into an “elephant with fishes” or as a fish in its aquarium[DB1] [1], but the “Man in a suit” is clearly the artist’s most successful combination of painted decoration and sculptural shape in vessels of its kind.

Representing a body by means of a vessel –a body mass by means of a hollow object– is the common feature of all the three-dimensional ceramic pieces conceived by Picasso in his preliminary sketches. In addition, despite their obvious sculptural quality, these ceramics are primarily assembled from pieces previously thrown on the potter’s wheel, and are true vases or sculptures dominated by an aesthetic deriving from a vase.

The existence of preliminary sketches dated by the artist himself anticipate part of his ceramic production, hence proving that it was not just a fortunate chance discovery, but rather the result of a deliberate pursuit that developed directly from Picasso’s former artistic quests and concerns. (Fig.29)

It is important that an analysis of the true value of Picasso’s ceramic output be pursued by art historians, and that researchers have the appropriate and fullest means for carrying out the long-term effort that is required given Picasso’s prolific production in this medium and the complexity of the subjects, concepts, and techniques employed by an artist for whom art was a true vehicle of knowledge.

As he once explained to his friend the photographer Brassai, “Why do you think I date everything I make? Because it’s not enough to know an artist’s works. One must also know when he made them, how, under what circumstances. No doubt there will someday be a science, called “the science of man,” perhaps, which will seek above all to get a deeper understanding of man via man-the-creator [...] I often think of that science, and I want the documentation I leave to posterity to be as complete as possible […]. That’s why I date everything I make.”[2] (Fig.30)

Colored pencil and India ink on paper.

Private collection.

© Succession Picasso 2020.

Wine pitcher in turned white terracotta, painted with a black, green and brown slip and engraved on a white enamelled ground, under glaze.

Private collection.

Photo credit: Maurice Aeschimann

© Succession Picasso 2020.

Large white terracotta vase, painted in reserve with blue, green and yellow oxides under partial glaze.

Private collection.

Photo credit: Maurice Aeschimann

© Succession Picasso 2020.

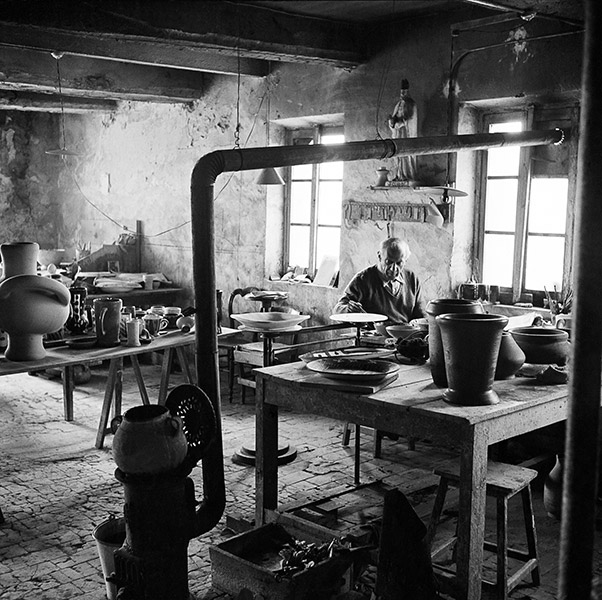

Photograph by Edward Quinn.

© Edward Quinn, edwardquinn.com

© Succession Picasso 2020.

Photograph by André Villers

© ADAGP, 2020 / ADAGP Images.

© Succession Picasso 2020.

Summary

Summary