During his vacation with Françoise Gilot on the Côte d’Azur, in late July, 1946, Picasso visited the Madoura pottery studio in Vallauris, run by Suzanne and Georges Ramié.

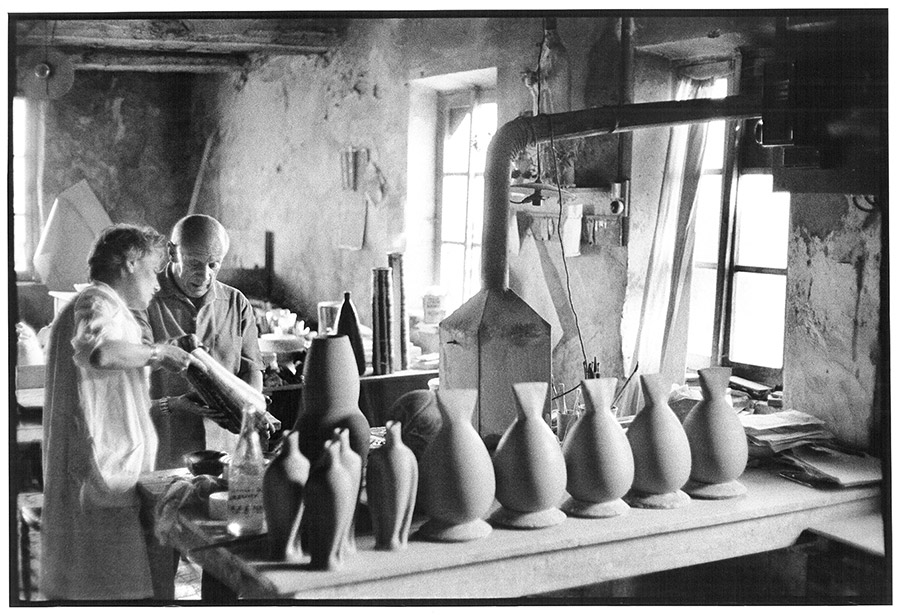

On July 26, 1946, Jules Agard, the master potter at Madoura, threw three clay pieces for Picasso, who then proceeded to modify them, one of which is the Head of a Faun,[1] made up of a previously thrown hollow shape that was then modeled by the artist and mounted on a small base. In late July 1947, Picasso returned to the Madoura studio and began an intense creative process with the Ramié couple’s team. (Fig. 1)

At Madoura, the workshop established in 1938, functional pieces –plates, vases and a variety of vessels– were produced in series following traditional Provençal standards. Suzanne Ramié also reinterpreted functional objects placing the emphasis on a balance between plasticity, volume and outline. Using the faïence technique, the pieces were fired at low temperature (960-980°C) in a traditional kiln fed with pine wood that was used up until 1954. Towards the end of 1947, a small electric kiln was installed in the studio as well.[2]

Picasso first experienced ceramics during his adolescence, but it was not until the summer of 1947, at Madoura in Vallauris, that he embarked on a prolific venture in this area, creating two thousand unique pieces before the end of 1948. He continued to pursue his ceramic work thereafter, producing over three thousand unique pieces up until 1971, when he was ninety years old. (Fig. 2)

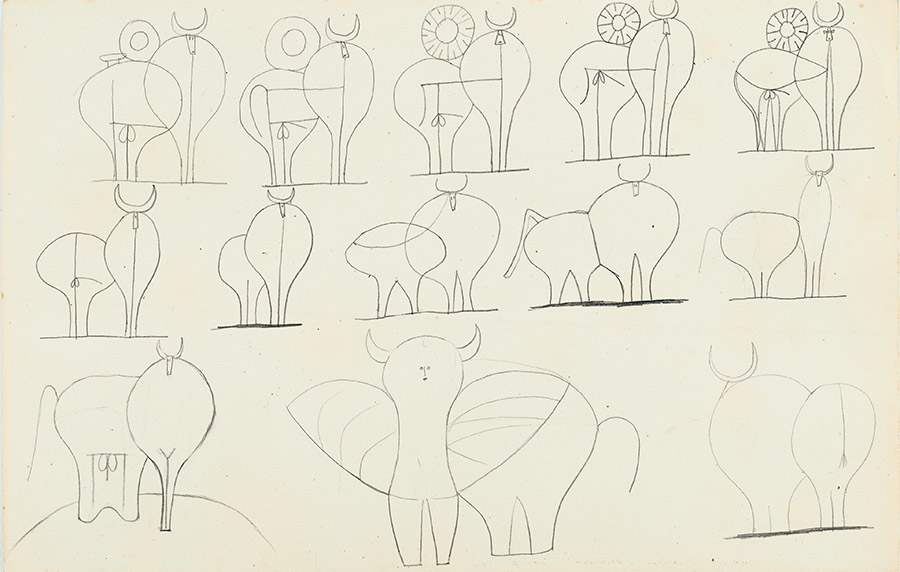

In Picasso’s ceramics, experimentation and improvisation play a major role. At Madoura, he explored all aspects of the medium, both at a formal and at a technical level. Mixing sculpture, painting, and printmaking techniques, he succeeded in creating new plastic forms that had interested him since he first began making his polychrome cubist sculptures and assemblages of objects, and which would have a visible impact on his entire subsequent production.[3]

Picasso’s strong tendency to transform objects into figurative representations led him to express himself in this medium both as a painter and as a sculptor. For the artist, the three-dimensionality of ceramic objects opened up new horizons for making art, allowing him to endow them with semantic and conceptual significance due to his use of surface and volume as fundamental principles.

Picasso worked with objects before they were fired, either modeling them or assembling them to transform them into three-dimensional figurations, or using them as supports on which to paint. He applied this approach to all the ceramics available at Madoura as well as to his own creations, prepared according to preliminary sketches and drawings.

[1] Werner Spies / Christine Piot, Picasso Sculpteur, Hatje Cantz-Verlag Ostfildern / Editions du Centre Pompidou Paris, 2001, (Spies) no. 378 A.

[2] Jean Ramié, “Précis technique – Les recherches de Picasso,” in the exhibition catalogue Picasso céramiste à Vallauris – Pièces uniques, Paris, Chiron 2004, pp. 61-67; Alain Ramié, letter to the author dated April 25, 1997; Yves Peltier, “Madoura : A workshop and a working community” in the exhibition catalogue Picasso and Ceramics, Quebec, Toronto, Antibes 2004-05, Paris, Hazan 2004, p. 121.

[3] For example, Glass of Absinthe, 1914, Spies no. 36 a-f ; Woman in the Garden, 1927, Spies 72 I.

© DD Duncan © Succession Picasso 2020

© edwardquinn.com

© Succession Picasso 2020

© FABA Photo: Eric Baudouin

© Succession Picasso 2020

Summary

Summary