Through the pictures of David Douglas Duncan

B. G.: Looking at David Douglas Duncan’s photos from La Californie with the children, one gets a sense of magical moments together. Can you tell us about them?

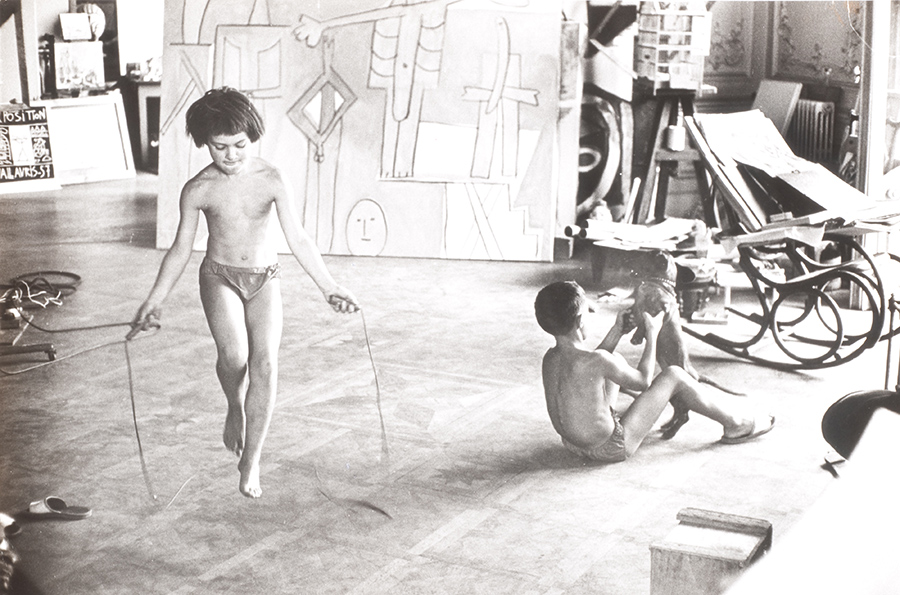

Yes, that’s exactly what you sense when you see the photos of us with Picasso when we were kids. There was Duncan, but Edward Quinn started doing his photo reports much earlier. Quinn was somewhat more formal and staged; it was journalism. Duncan’s work is rawer, showing things just as they were. It’s as if he didn’t exist; he was there, but unobtrusive. He had a more natural approach to what was happening. It’s also a performance of sorts, because you see things differently, it gives you a more natural view of what was happening.

Going back to the previous pictures, to Quinn’s journalistic work, showing parents with children drawing—the father, who happens to be Picasso, guides the child through several images, shows him simple objects: a pot, a cat, whatever. In this sweetened version of reality, I was asked to draw Picasso’s portrait. It was funny; I drew the portrait, but you could see it wasn’t very natural. On the other hand, what is very real about the pictures is that we kids were always around, doing things, and that Picasso would occasionally look at what we were doing. In Duncan’s photos and others, but particularly in Duncan’s, it’s clearest because he had sort of set up shop there, we were around the table, we’d just had lunch, we were clearing the table and were starting to draw. There was no specific subject. Picasso came over and sat down with us; it was normal, like in a family.

What comes to mind about those captured moments? To me, they were normal, everyday occurrences. A lot of what we would do as kids happened outside the studio. We would play art-related games, for example. We would make galleries, invitations to openings, copy gallery doors, and obviously make the paintings for the show, for example, a view with a three-mast schooner, the kind of painting that you would see in an art gallery. Everyone found it amusing, and then he made some, too. We used the bottoms of matchboxes for the size of the paintings. It was silly. We did things like that, which could have happened anywhere, in another family.

He’d make lots of musketeer paper cutouts. He would fold and cut paper to make a bunch of musketeers. You could draw on the front or the back and we had one each. They were Picasso’s musketeers, but not entirely his, because they were drawn by the different kids—Paloma, Catherine, Inès’s son Gérard, and me. We tried to make them, too, we did our little copies.

Summary

Summary