Sharing the beauty of the world

Prévert observed Picasso and bore witness in his writing to the artist’s spontaneity, to his ability to devise and produce works out of the smallest of things –an object, a piece of cloth, a scrap of paper or a simple nail. He voiced his surprise in his poems, particularly in Paroles, published in 1946. Both in his film scripts and his other writings, Prévert’s poetic realism was in sync with Picasso’s artistic gesture. Both had a tendency to admire the beauty of the world while remaining aware of the cynicism of mankind. Prévert wrote pieces in which he combined intimacy with politics and called out the delusions of society. The words of the one and the positions of the other converged. Their intense activity along with their aesthetic and political commitment only strengthened the bond of their friendship over the years. Needless to say, they were also united by their fierce attachment to their freedom of thought.

Each in his own way, they both applied a sense of observation and a piercing, willingly mischievous gaze to translate their view of a world full of beauty but at times cruel and unjust. They both evoked it with a mix of humor, derision, and tragedy. Prévert excelled in this respect in his screenwriting, working joyfully and chaotically on what Aragon referred to as his grifouillis[1]; he produced several masterpieces, in particular with Marcel Carné. Film was very important to Prévert, who was especially fond of the team effort it involved –unlike Picasso, who preferred to work alone.

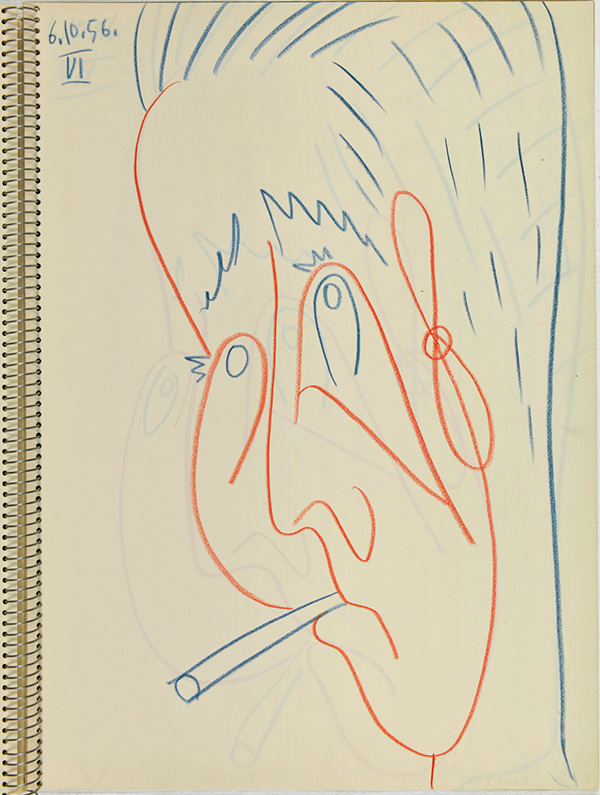

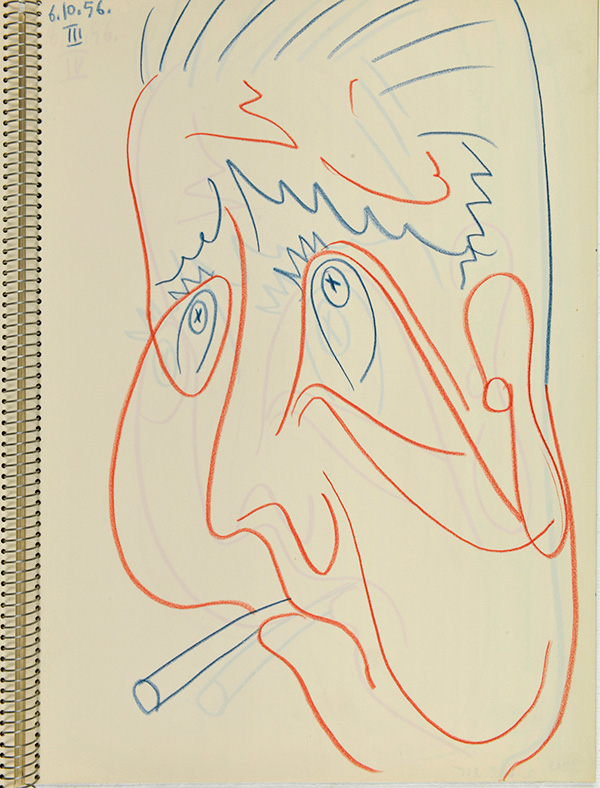

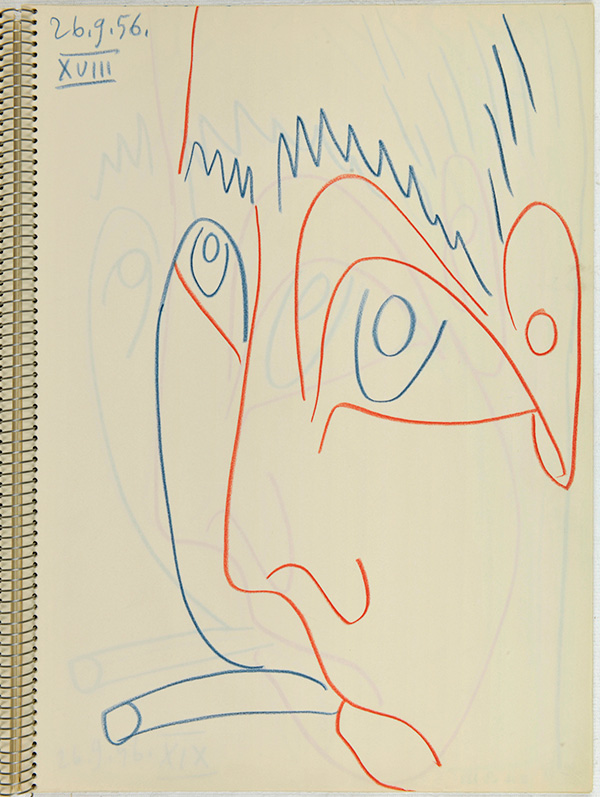

Without melancholy, the painter and the poet were both serenely aware of their duty: to convey what life had taught them, through language, through words, and through painting or images. This symbiosis was what enabled them to collaborate. They both fought for the recognition of popular culture, to which they felt connected. They also shared the pleasure of capturing glimpses of daily life, the language of the marvelous, the weaknesses of their contemporaries, as well as everyday pleasures: a pipe, a cigarette, the page of a magazine, a glass of wine, a cooking pot, say it all. Much before Prévert, since 1912 Picasso had been opening up a realm of experimentation that matched his talent for all sorts of handicrafts. His “pasted papers” led to endless variations on the themes arising from his imagination.

His creations took an increasingly complex turn with his assemblages, relief paintings, and encounters with space. The artist opened up his compositions, working everyday elements into them, objects from daily life, and then, any item from his surroundings. Drawings enhanced with newspaper clippings or pinned with upholstery swatches, combinations of built objects and wallpaper, a few strokes of chalk or charcoal, were all it took for the painter to brilliantly reformulate reality. Prévert, a man of strong emotions, expressed himself in his collages as he did in the words of his poetry. He used striking ideas and mottos with straightforward, generous loquacity. “Jacques Prévert attacks everything he hates –war, poverty, the bourgeoisie– and hails what he loves –free love, childhood, the simple joy of living.”[2] For Prévert, the different means of expression were all based on the same process: the art of montage.

Summary

Summary