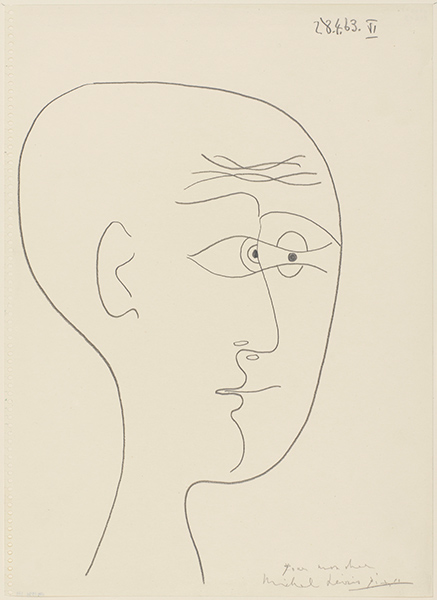

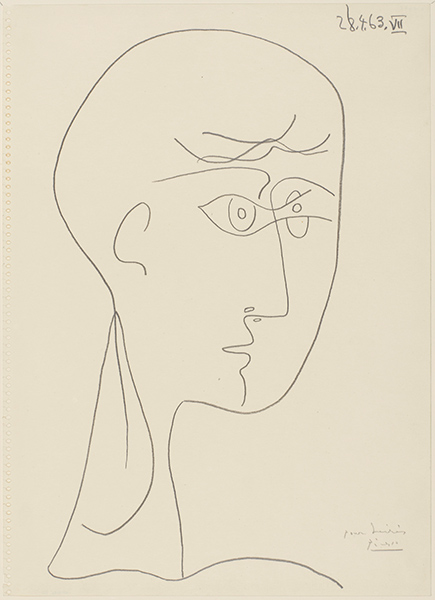

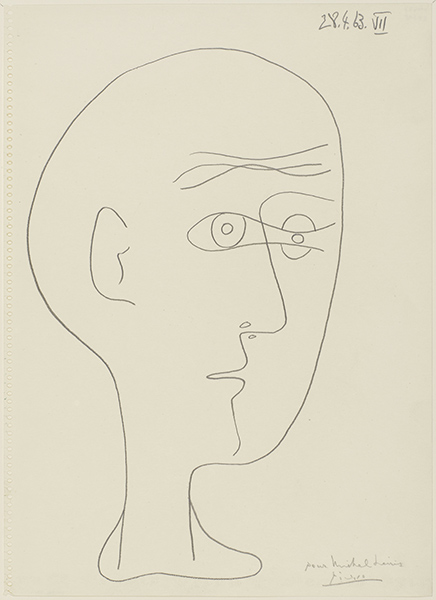

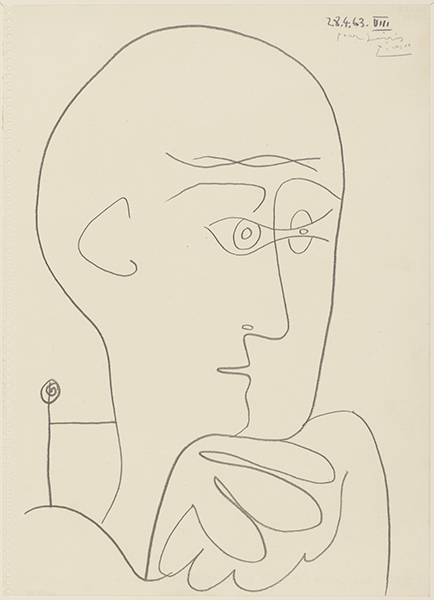

Michel Leiris, writer and ethnographer

As a writer of his times, we will probably agree that few are as representative as Michel Leiris. A surrealist in 1924 and a communist two years later, he joined Documents magazine in 1929. He was on an ethnographic expedition to Dakar-Djibouti, in psychoanalysis, and at the Musée de l’Homme. He produced writings that had an impact on a variety of fields: L’Afrique fantôme (Phantom Africa, 1934), autobiographical exploration in L’Âge d’Homme (Manhood, 1939) and La Règle du Jeu: Biffures, Fourbis, Fibrilles, Frêle bruit (Rules of the Game, a set of four biographical accounts published between 1948 and 1976), and even bullfighting (Miroir de la tauromachie–Mirror of Tauromachy, 1938).

A large part of the author’s Écrits sur l’art (writings about art) reveals his ongoing and sensitive relationships with the artists of his time. "The writer ended up overshadowing the ethnographer, although they remain inseparable. Leiris's scholarly writings are texts, his literary works are informed by an introspective ethnographic approach that he turned upon himself. The other, in his singularity, and foreign cultures, in their differences, necessarily lead to an inward quest. The ethnography of the other is also an ethnography of the self; only Michel Leiris was able to fully acknowledge this obligation and carry it to its ultimate consequences," wrote Georges Balandier upon his death on September 30, 1990.[1] Leiris was also careful to cover his tracks, describing himself as "a crab walking sideways," "a maniac who has never been out of control," "a revolutionary who is paralyzed by his habits and who faints at the sight of blood," and "an atheist moon-worshiper."

As Philippe Lejeune notes, "critics always find it difficult to discuss Leiris. Every essay on method risks being rendered ridiculous by Leiris's method: like casting stones against the wind, plowing the sands. […] Leiris's works are systematically and deliberately built upon the basic processes that exploit the structures highlighted by the "human sciences." And his knowledge of the human sciences is not, as it is for many critics, a bookish, superficial learning. It is the experience originally acquired in his work: his playful decomposition of poetic language ever since 1925, his discourse as an analysand in the course of his treatment, his work of a professional ethnographer, his founding of the Collège de Sociologie jointly with Bataille and Caillois, etc."[2]

Disconcerting in every respect, his work remains fascinating and complex.

[1] Le Monde, October 3, 1990

[2] Philippe Lejeune, Lire Leiris, autobiographie et langage, Klincksieck, 1975, available online (in French) at the author's website, www.autopacte.org

Summary

Summary