By then her reputation was well established. Several tapestries that had come out of her project were purchased for the prestigious collection held by Albert C. Barnes. Thanks to this man's support, she exhibited in leading U.S. museums from 1936 on. Marie Cuttoli's role as a catalyst was unanimously acknowledged. She wrote: "Relying on the age-old traditions that have been kept alive by the artisans of our country, once the cradle of medieval tapestry, I have attempted to put this vast traditional wealth at the service of the most alive art, the boldest, the art that most approaches the richness of the avant-garde." She was the instigator of the revival of tapestry. A friend of artists, she also became their firm advocate and fought untiringly to defend them, showing her collection even to the most reticent: "There is nothing to explain. I can assure you that it is admirable. Do not reject this painting from the start: try to understand it, to feel it." Challenging trends and individuals, over the years she became a key figure in the art world.

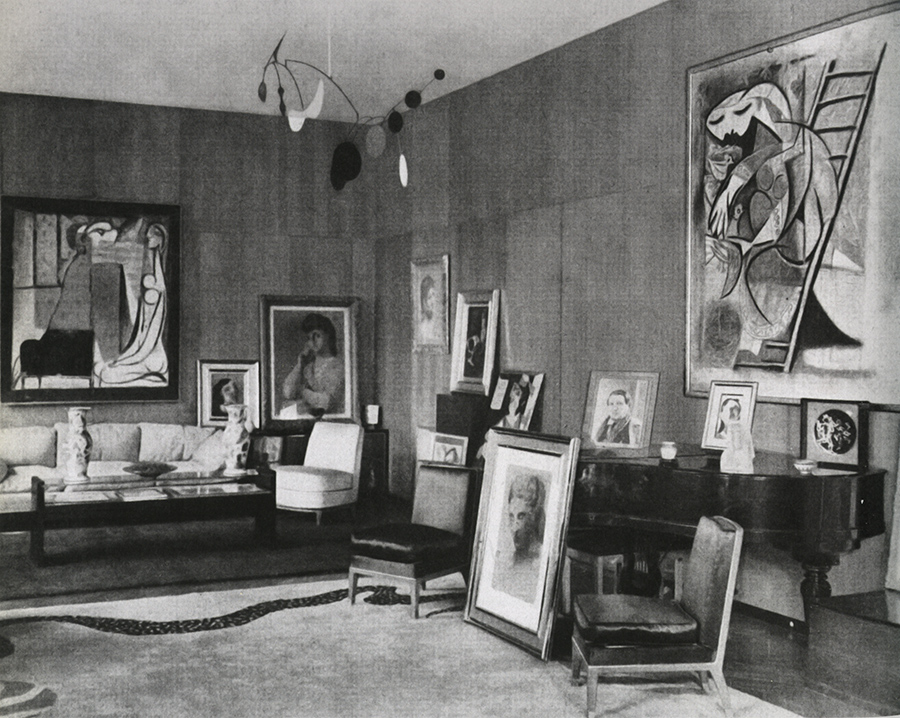

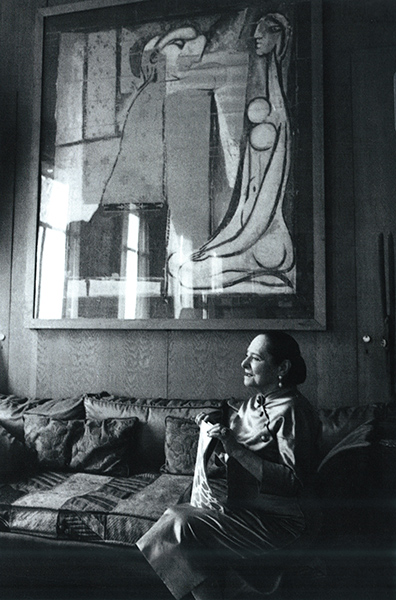

She moved to rue de Babylone in 1935, to a split-level apartment large enough to house the couple's works of art. Sheltered from the hustle and bustle of city life, their opulent, warm home held a collection of exceptional value, which the reviews described as one of the "landmarks of contemporary art." There were paintings everywhere: the eye skipped from one to the next, all vying for attention. Picasso, whose broad range of techniques and disconcerting hand Marie Cuttoli valued above all, held a place of honor. In the living room, La fermière (Femme aux pigeons) presided over the piano; the large Confidences pasted papers and a 1921 pastel, Femme accoudée, hung on the side wall. Another room was dedicated solely to his work. That same year, she joined forces with Jeanne Bucher, whose talent for discovering upcoming artists had earned her an outstanding reputation. Faithful and devoted, she defended those artists whose work she loved, developing a climate of mutual trust with them. The two women found a lovely house between Duroc and Montparnasse, which they then shared with Georges Hugnet, a collage artist, poet, critic, historian of surrealism and dadaism, and editor who moved into the second floor. He was also the founder and editor-in-chief of the literary magazine L’Usage de la parole, published by Cahiers d’art from December 1939 to April 1940.

Summary

Summary