La vie, a complex and long amended artwork

La Vie is one of the iconic paintings of Picasso’s last years in Barcelona that still contains a few unanswered questions. Although there is no irrefutable evidence of when it was begun, it is dated roughly to May 1903, a time when Picasso was working in a studio on Riera de Sant Joan (a street that no longer exists), and marked the culmination of a fruitful creative spell in Barcelona when his Blue Period was drawing to a close.

Despite the fact that we still do not know when the work was actually finished, it is believed that it was sold shortly afterwards; [1] nevertheless, the process of its making, its completion and its sale are still a mystery. Only the analysis of the inner layers of paint, carried out in 2010 by the Cleveland Museum of Art in scientific collaboration with the Indianapolis Museum of Art, has managed to shed some light on the work by singling out successive strata of colour[2] and establishing the mineralogical nature of some of the pigments in the underlying, and therefore invisible, layers. Today we know that the work has a complex structure resulting from a long process of execution[3] that entailed significant formal changes, as regards both the composition and the palette.

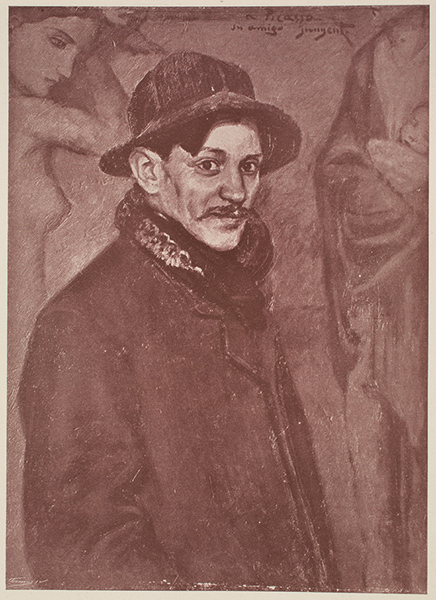

Other relevant documentary sources are the various preparatory drawings dated by the artist, and the painting of Sebastià Junyent (fig. 1) that depicts Picasso himself, dressed in winter wear, in front of La Vie, a detail that helps us place the scene in context.

In order to better understand the composition and the state of conservation of the paintings, over the past two decades some institutions,

including Museu Picasso in Barcelona, have carried out physiochemical analyses of some of Picasso’s works. These studies have brought to light other underlying compositions related to La Vie that would suggest that, far from being an isolated work, it can be considered the main visible link in a chain of scenes that were abandoned along the way. Most of them are found beneath the chief paintings of his Barcelona years or else were modified years later.[4]

Many works in his Blue Period were sold quickly to the chief early twentieth-century art collectors[5] and were later acquired by different museum.[6] For many years a general attitude unfavourable to researching the creative process of art, coupled with the international dispersal of Picasso’s oeuvre have hindered comparative studies of his production, preventing scholars from establishing documentary ties between works based on direct and objective knowledge of their materials, techniques and structure. As a result, for most of the twentieth century those works that the artist disregarded during the creative process have gone unnoticed, even if they were archetypes for certain masterpieces, as in the case of Barcelona Rooftops.

Today, new methods of examining, based above all on technical imaging and chemical analyses of materials, along with a general desire to further our understanding of creative processes, are coming up with valuable data, enabling us to draw up an inventory of the artist’s hidden oeuvre that will no doubt make it easier to study in context. Art and science finally come together in an interdisciplinary approach.

Over a century after it was produced, La Vie returns to Barcelona to be considered in relation to some of the works that were no doubt instrumental in its making. Most of these are well known and well documented drawings; others, like Barcelona Rooftops, contain information that has now been revealed and forms a part of the documentary archive of this hidden museum.

[1] An article published in El Liberal on 4 June announced its sale to a French collector, apparently a fictitious character of whom nothing further is known.

[2] Dean Yoder is restorer of painting at the Cleveland Museum of Art and Gregory Smith is scientific restorer at the Indianapolis Museum of Art. To date, their study has identified the blue and black pigments in the pictorial composition..

[3] The X-ray study made in 1978 revealed the painting Last Moments as well as the hidden portrait of the artist, but the pigments used in the intermediate layers remained to be identified.

[4] Fernande Olivier tells us that on her first visit to the Bateau Lavoir atelier in the summer of 1904 Picasso was busy covering up a previous painting: ‘The paintings he’s doing are quite different from those I saw when I first came to the studio last summer, and he’s painting over many of those canvases. The blue figures, reminiscent of El Greco, that I loved so much have been covered with delicate, sensitive paintings of acrobats…’ Loving Picasso: The Private Journal of Fernande Olivier. New York, Harry N. Abrams Inc., 2001, p. 162.

[5] Collectors like the Sten brothers or Sergei Schukine managed to secure a large representation of works from Picasso’s Blue Period and presented these acquisitions in their private salons, to narrow circles.

[6] Schukine’s collection became public property in 1918 when it was 1 See the photograph dated 1915–16 of confiscated by the Soviets.

Summary

Summary