Drawings and paintings resembling the image of the underlying layer

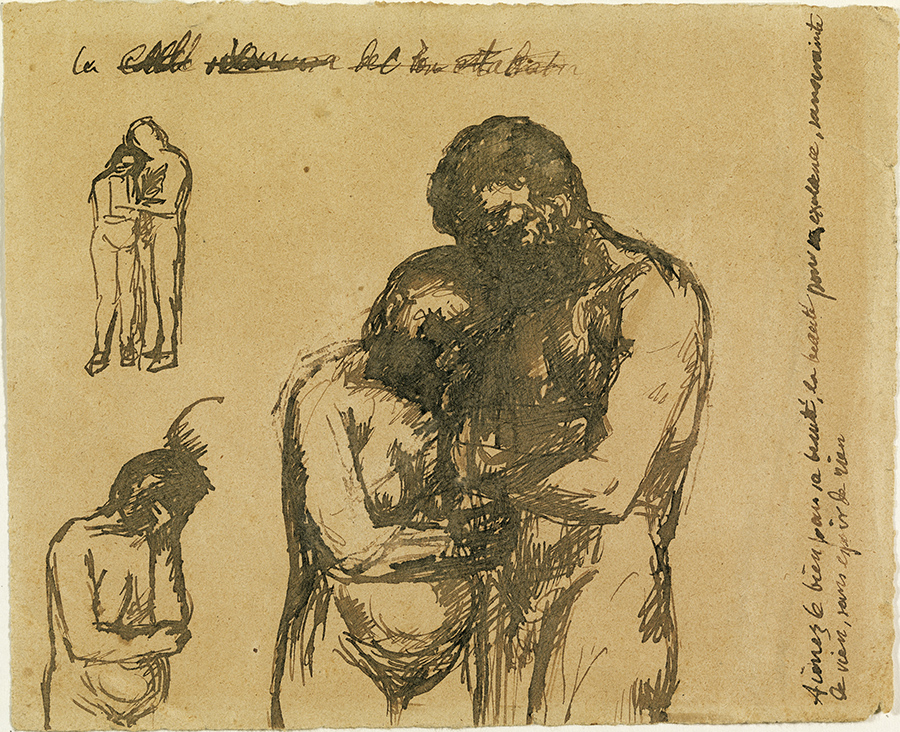

Among the documented drawings from this period Study for La Vie[1] is certainly the one that bears a closer relation to the X-ray image obtained in Barcelona Rooftops, as determined by obvious coincidences such as the inclination of the female head and the bearded man standing up (cat. 15, p. 95).[2]

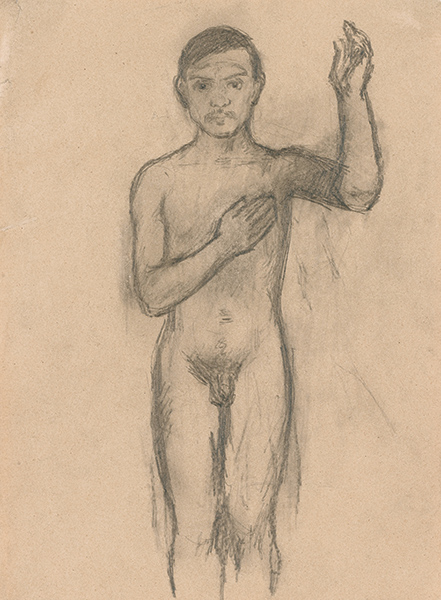

Unlike the version painted beneath Barcelona Rooftops, in this drawing the couple appears seen from the front and walking side by side. The artist is more concerned with modulating light, through shading, than with the uneven trace of the wavering line. The inclination of the female head is more marked here and closer to the infrared image previously described. [3] Behind the image we discover a correction, almost erased, that suggests that the male figure was initially in a more upright position that revealed his right hand and a part of his head. This arrangement evokes that of the small pencil drawing Self-Portrait with Raised Arm (fig. 7) made in Paris in the winter of 1902–03, in which the artist, brazenly undressed, is depicted from the front.[4]

Another similar composition with unfaltering lines is the small ink sketch entitled Study for La Vie (cat. 16, p. 96). Neither of these two preliminary works contains spatial references that help us place the scene in a specific setting, not even the line in the shape of an arch in La Vie that we come across in other paintings such as Two Sisters (The Meeting), currently in the collection of the Hermitage in St Petersburg.

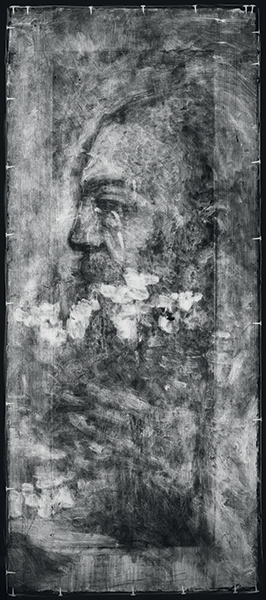

As regards the identification of the characters, the female type in the painting beneath Barcelona Rooftops and other drawings of the period still appears with dark hair and sensuous curves, while the man is portrayed according to the canons of the time. This bearded archetype, indebted to the classicism of Puvis de Chavannes,[5] appears in a number of drawings, as well as in an underlying painting entitled The Blue Glass kept in the Museu Picasso collection. As well as bringing to light the head of a man, a close study of the X-ray of the latter revealed Picasso’s signature scratched into the fresh paint, which would suggest that the work was more than a mere preliminary sketch (figs. 9 and 10, p. 42).

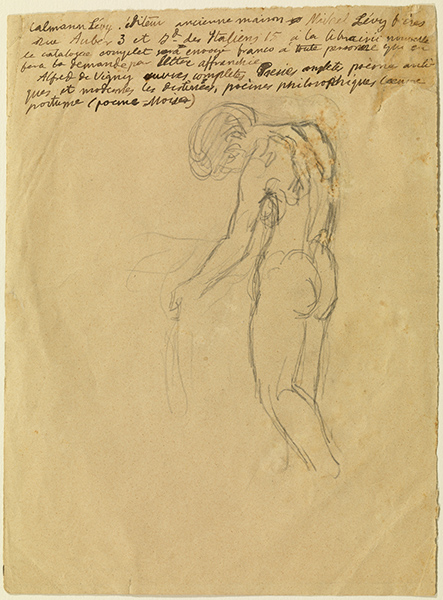

The couple is inspired by the robust figures that the artist often depicted interwoven, almost as a single block, in contrapposto, a recurring theme in his works of the years 1902 and 1903 that concluded with the great work La Vie. Picasso analysed the human figure in detail, and by studying its anatomical possibilities in depth and from various points of view managed to produce very different compositions. Thus, the posture in Study of Nude and Text (fig. 8, p. 41) is similar to that of the female figure discovered beneath Barcelona Rooftops, albeit depicted from the opposite side.

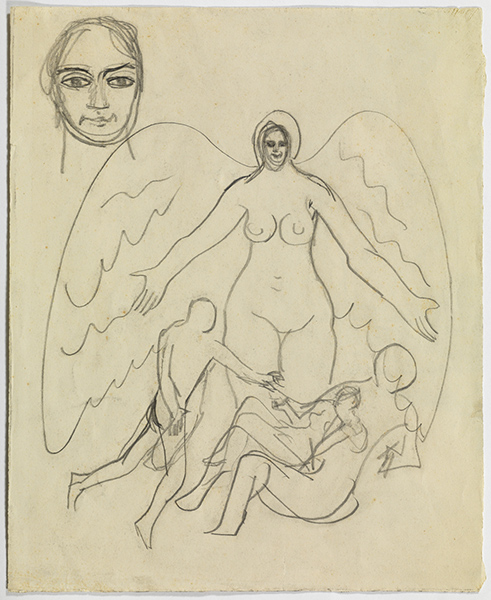

We cannot overlook the fact that the position of the woman evokes that of the figure in the small oil painting Female Nude (cat. 9, p. 85), who is portrayed with arms outstretched, her palms facing the viewer, and long hair, symbolic attribute of the femme fatale. In our underlying image the figure begins to rotate on its axis, hiding the palm of her right hand yet still opening her left hand, a feature that relates the work formally to the disturbing drawings entitled Allegorical Sketches (cats. 6 and 7, pp. 82-3).

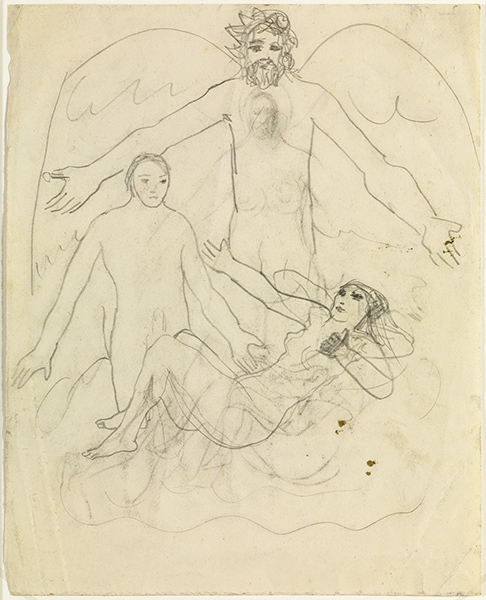

Months before starting work on La Vie in May 1902, Picasso made several drawings of winged characters, male and female, and their presence is another of the elements still to be deciphered in this painting. Research into their possible origin has led to a number of varied interpretations that range from Christian imaginary to the world of palmistry and tarot.

In the recent monographic exhibition dedicated to La Vie at the Cleveland Museum of Art,[6] William Robinson studied the work’s connections with sculpture, taking Rodin as a reference. In our opinion this approach could be enhanced by the study of other artists such as sculptor Ricardo Bellver y Ramón (Madrid 1845–1924), who was awarded a scholarship to attend the Spanish Academy in Rome in 1875. During his third year in the Italian capital Bellver produced an allegorical sculpture of The Fallen Angel (fig. 11) that was displayed at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1878 and was eventually installed in the square at the Retiro Park in Madrid in 1885. Picasso visited the space on his trips to Madrid, and made several sketches from life of the sculpture.

[1] Z VI, 440, private collection.

[2] Not dated or signed.

[3] In the section entitled ‘Description of the underlying image’ in this text.

[4] The configuration of Self-Portrait with Raised Arm is also reminiscent of the masculine figure in the underlying layer of Barcelona Rooftops.

[5] ‘The trace of Puvis de Chavannes (1824–1898) cannot be ignored either, whose classicism inspired that of Cézanne, on the one hand, but also influenced the pursuits of Picasso and Matisse.’ Francisco Calvo Serraller, ‘Picasso frente a la historia’, in Francisco Calvo Serraller, Carmen Giménez (eds.), Picasso. Tradición y vanguardia [exh. cat.]. Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado / Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2006, p. 37. Our translation from the Spanish.

[6] William H. Robinson, Picasso and the Mysteries of Life: La Vie. Cleveland, The Cleveland Museum of Art / D. Giles, 2012.

Summary

Summary